#14,339

Epi Week 40, which this year began yesterday (Sunday Sept 29th), signals the start of the 2019-2020 flu reporting season for the CDC, as well for many other agencies in the Northern Hemisphere.

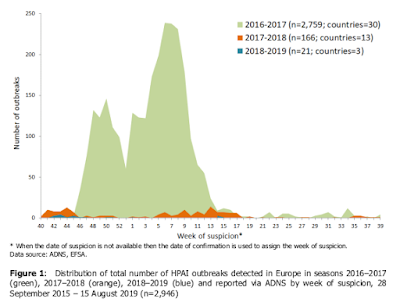

By the first week of October, the temperatures are growing cooler and the air drier, schools are back in session, and migratory birds - which have spent their summer roosting in the high latitudes - are moving south to warmer climes.All ingredients that are associated with increased spread of flu - both in humans and in other species. The map above shows the spread of avian flu in Europe over the past 3 years. The impressive twin-peaked mountain (in green) signifies Europe's disastrous avian zoonotic of 2016-2017.

The following year (2017-2018) is shown in orange, and this latest year (2018-2019) barely shows up as tiny blue blips.If we were to look further back, to 2015-2016, it would look very much like this past year; with only a smattering of avian flu reports. Quiescence - while welcome - can change very quickly.

As the chart above indicates, heavy bird flu seasons are often followed by one or more less active years, likely due (in part) to acquired immunity in wild birds, and enhanced biosecurity measures taken by poultry interests.

In 2015 - following North America's record HPAI H5 epizootic - we looked at a study (see PNAS: The Enigma Of Disappearing HPAI H5 In North American Migratory Waterfowl) which concluded that - while migratory waterfowl can briefly carry HPAI H5 - they were not a very good long-term reservoir for highly pathogenic avian flu viruses.

HPAI viruses, they posited, burned out fairly quickly in aquatic waterfowl populations - likely due to their immunity to LPAI viruses - and would therefore have to be reintroduced periodically.A study, published in 2016 (see Sci Repts.: Southward Autumn Migration Of Waterfowl Facilitates Transmission Of HPAI H5N1), suggests that waterfowl pick up new HPAI viruses in the spring (likely from poultry or terrestrial birds) on their way to their summer breeding spots - where they spread and potentially evolve - and then redistribute them on their southbound journey the following fall.

Meaning that what we see this fall in winter could well depend upon what avian viruses have been circulating among birds in the high latitudes over the summer, and will be carried south by migratory birds for the winter (see WHO: Migratory Birds & The Potential Spread Of Avian Influenza).

While we wait to see what this year's migratory season will bring, we've the ECDC's latest twice annual review of avian flu activity in Europe, which details (in a 38-page PDF) a very subdued avian flu landscape thus far in 2019.

Avian influenza overview February – August 2019

European Food Safety Authority,

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and

European Union Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza

Cornelia Adlhoch, Alice Fusaro, Thijs Kuiken, Isabella Monne, Krzysztof Smietanka, Christoph Staubach, Irene Muñoz Guajardo and Francesca Baldinelli

Abstract

Between 16 February and 15 August 2019, five HPAI A(H5N8) outbreaks at poultry establishments in Bulgaria, two low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) A(H5N1) outbreaks in poultry in Denmark and one in captive birds in Germany, one LPAI A(H7N3) outbreak in poultry in Italy and one LPAI A(H7N7) outbreak in poultry in Denmark were reported in Europe.

Genetic characterisation reveals that viruses from Denmark cluster with viruses previously identified in wild birds and poultry in Europe; while the Italian isolate clusters with LPAI viruses circulating in wild birds in Central Asia. No avian influenza outbreaks in wild birds were notified in Europe in the relevant period for this report.

A decreased number of outbreaks in poultry and wild birds in Asia, Africa and the Middle East was reported during the time period for this report, particularly during the last three months. Furthermore, only six affected wild birds were reported in the relevant time period of this report. Currently there is no evidence of a new HPAI virus incursion from Asia into Europe. However, passive surveillance systems may not be sensitive for early detection if the prevalence or case fatality in wild birds is very low.

Therefore, it is important to encourage and maintain passive surveillance in Europe encouraging a search for carcasses of wild bird species that are in the revised list of target species in order to detect any incursion of HPAI virus early and initiate warning. No human infections due to HPAI viruses - detected in wild birds and poultry outbreaks in Europe - have been reported during the last years and the risk of zoonotic transmission to the general public in Europe is considered very low.(SNIP)

Conclusions

Avian influenza outbreaks in European countries and in other countries of interest between 16 February and 15 August 2019

2.1. Main observations

• No human infections with HPAI or LPAI viruses of the same genetic composition as those currently detected in domestic and wild birds in Europe have been reported from the EU/EEA Member States.

• One human case caused by A(H5N1) in Nepal, two cases with A(H9N2) in China and Oman, one human case with A(H7N9) and one with A(H5N6) infection in China have been reported with onset of disease since February 2019.

• In Europe, between 16 February and 15 August 2019 (based on the Animal Disease Notification System (ADNS)):– five HPAI A(H5N8) outbreaks were reported in poultry in Bulgaria; phylogenetic analysis revealed that the viruses cluster with A(H5N8) European viruses collected during the 2016-2017 epidemic;

– five LPAI outbreaks were reported: two A(H5N1) and one A(H7N7) in poultry in Denmark, one A(H7N3) in Italy, and one A(H5N1) in captive birds in Germany. Genetic characterisation of the Danish isolates showed that they cluster with LPAI viruses previously identified in wild birds and poultry in Europe. Phylogenetic analysis of the Italian isolate revealed that the virus clusters with LPAI viruses circulating in wild birds in Central Asia.

• No HPAI cases in wild birds were reported in Europe during this reporting period.• Taking the half-year period of this report and the dates of notification into account, the number of reported outbreaks in domestic birds for Asia, Africa and the Middle East was lower than in the previous time period, particularly during the last three months. Furthermore, only six infected wild birds were reported in the relevant time period for this report.

2.2. Conclusions

• The risk of zoonotic transmission of AI viruses to the general public in Europe remains very low.(Continue . . . )

• In the current 2018–2019 season (from October 2018 to August 2019), compared with the previous 2017–2018 season (from October 2017 to September 2018), there is a decreased number of reported outbreaks in poultry in Europe.

• No cases of HPAI virus infection were reported in wild birds from key areas in Mongolia, western China, or Siberia; in previous years, such reports foreshadowed the incursion of HPAI virus in Europe via the autumn migration of wild birds.

• During the period for this report in the EU/EEA, there has been no evidence of any new HPAI virus incursion from Asia. However, passive surveillance systems may not be sensitive for the early detection of new incursion if the case fatality rate in wild birds is very low.

Major avian flu epizootics - such as visited North America over 2014-2015 and Europe over 2016-2017 - have been very limited outside of China and Southeast Asia, and we have very little data to tell us how often they might reoccur.

Hopefully this year will be just as quiet as the last. But if we know one thing about influenza viruses, it is that they are unpredictable. And so we'll have to be alert this winter once again for any surprises.