|

| Add caption |

#14,300

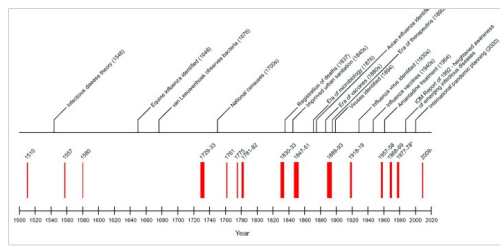

As we've often discussed (see Pandemic Influenza's 500th Anniversary by Morens, Taubenberger, Folkers,& Fauci) - while we only know the types of influenza that have circulated in humans since early in the 20th century - historic accounts suggest at least a dozen `influenza-like’ pandemics occurred in the 400 years prior to 1900.

|

| Pandemic Influenza's 500th Anniversary |

There's a lot of debate over these pre-1900 influenza pandemics, with conflicting views over whether the 1890-93 `Russian flu’ was due to the H2N2, H3N2, or H3N8 virus.

What we do know is over the past 130 years, all human influenza pandemics have been due to H1, H2, or H3 viruses (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?).While this doesn't preclude other subtypes from presenting a pandemic threat, history suggests that novel H1, H2, and H3 flu viruses currently have fewer barriers to overcome in order to jump to humans.

Some researchers have suggested we are overdue for an H2 pandemic (see J.I.D.: Population Serologic Immunity To H2N2 For Pandemic Risk Assessment), but novel H1, H2, and H3 viruses continue to circulate in a number of species (including birds, pigs, horses, dogs, etc.) and all three remain very much in play.

And one of the big lessons from the 2009 pandemic was that it doesn't take a subtype change in order to spark a pandemic. We'd likely have little immunity to a biologically `fit' novel H1N1 or H3N2 virus, and that could pose a significant pandemic threat.For that reason we keep close watch on a number of H1, H2, and H3 threats around the world, including:

PLoS One: Continuous Evolution of Influenza A Viruses of Swine from 2013 to 2015 in Guangdong, China

Emerg. Microbes & Inf.: Characterization of Swine-origin H1N1 Canine Influenza Viruses

J.O.I. : A Human Infection with a Novel Reassortant H3N2 Swine Virus in China

Prevalence, genetics, and transmissibility in ferrets of Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza viruses.

While swine-origin H1, H2, and H3 viruses have garnered the most attention, H1, H2, and H3 viruses also circulate in birds, and have jumped to other mammalian species (see Avian-origin H3N2 canine influenza A viruses in Southern China).

All of which brings us to a new study, published this week in Emerging Microbes & Infections, that examines 15 avian H3N2 viruses collected from poultry in China, and finds at least 5 of them well-enough adapted to mammalian hosts to present a potential threat to human health.

H3N2 avian influenza viruses detected in live poultry markets in China bind to human-type receptors and transmit in guinea pigs and ferrets

Lizheng Guan, Jianzhong Shi, Xingtian Kong, Shujie Ma, Yaping Zhang, Xin Yin, show all

Published online: 07 Sep 2019

ABSTRACT

The H3N2 influenza viruses became widespread in humans during the 1968 H3N2 pandemic and have been a major cause of influenza epidemics ever since. Different lineages of H3N2 influenza viruses are also commonly found in animals. If a different lineage of H3N2 virus jumps to humans, a human influenza pandemic could occur with devastating consequences.

Here, we studied the genetics, receptor-binding properties, and replication and transmission in mammals of 15 H3N2 avian influenza viruses detected in live poultry markets in China.

We found that the H3N2 avian influenza viruses are complicated reassortants with distinct replication phenotypes in mice. Five viruses replicated efficiently in mice and bound to both human-type and avian-type receptors.

These viruses transmitted efficiently to direct-contact guinea pigs, and three of them also transmitted among guinea pigs and ferrets via respiratory droplets.

Moreover, ferret antiserum induced by human H3N2 viruses did not react with any of the H3N2 avian influenza viruses. Our study demonstrates that the H3N2 avian influenza viruses pose a clear threat to human health and emphasizes the need for continued surveillance and evaluation of the H3N2 influenza viruses circulating in nature.(Continue . . . )

This is a lengthy and detailed (open-access) research paper, and you'll probably want to read it in its entirety. For those pressed for time, however, I've extracted a few highlights from the Discussion section.

Discussion

Here, we extensively characterized 15 H3N2 avian viruses that were isolated from live poultry markets in China, and found that H3N2 viruses circulating in avian species in nature have undergone frequent reassortment and formed complicated genotypes.

The H3N2 avian viruses were antigenically similar but did not react with ferret antisera raised against representative human H3N2 viruses that were isolated between 2007 and 2017. Five of the 15 H3N2 avian viruses replicated efficiently in mice and bound to both avian-type and human-type receptors; moreover, we found that all five of these viruses transmitted efficiently to contact guinea pigs and three of them also transmitted to guinea pigs and ferrets via respiratory droplets.

Gene reassortment is an important mechanism for influenza virus evolution. Our phylogenic analysis indicated that the gene segments of the H3N2 viruses originated from different subtypes of influenza viruses previously detected in wild birds or ducks, suggesting that different influenza viruses are co-circulating and gene reassortment occurs frequently among these avian species.

The fact that the 15 viruses formed 15 genotypes shows that the H3N2 viruses may not have formed a stable lineage in domestic poultry. Previous studies indicate that H9N2 influenza viruses provided their internal genes to the H7N9 and H10N8 viruses that have caused human infections in China.

Given that the H9N2 viruses are actively circulating in the live poultry markets the H3N2 avian influenza viruses may also acquire the internal genes from the H9N2 viruses and adapt in domestic poultry or even “jump” to humans.

(SNIP)

Given the biologic properties of H3N2 viruses we reported here, human infection with the H3N2 avian viruses will be inevitable. Ferret antisera against different recent H3N2 human viruses did not cross-react with any of the H3N2 avian viruses in our study, which suggests that preexisting immunity may not be able to limit the spread of the H3N2 avian viruses in humans.

Our study has thus revealed the risks to human health posed by H3N2 avian viruses and emphasizes the importance of continuous monitoring and evaluation of the H3N2 influenza viruses circulating in poultry.(Continue . . . )

The above stated`inevitability' of human infection doesn't guarantee a pandemic, of course. We've seen numerous `one-off' or sporadic human infections from a variety of novel viruses over the years (H10N8, H10N7, H5N6, H6N1, etc.).

It's highly likely that one or more of these avian H3N2 viruses has already made the jump to humans, but wasn't `fit' enough to spread.But every exposure, and every species jump, provides another opportunity for these viruses to adapt humans. And as we saw in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, once a virus makes the right `adjustments', things tend to move very quickly.