|

| NOAA Heat Index Through July 3rd |

#15,340

Normally, at least once every summer, I write about the toll that heat waves take on the public's health, and ways to reduce your risks of heat stroke or heat exhaustion. Studies suggest that excessive heat has likely killed more Americans over the past half century than all of the tornadoes, floods, and hurricanes combined.

The problem is, during our COVID pandemic, many of the usual remedies (particularly for those without air conditioning) - such as going to the park, or the beach, or perhaps to a shopping mall - entail risks of their own.

Add in the potential for power outages due to excessive demand, or storm damage, and even those with air-conditioning can find themselves sweltering in place this summer.

In late June of 2012 an unusually strong storm front, known as a Derecho, swept across parts of the Eastern United States – killing 15 people – and leaving millions without electrical power for more than a week (see Picking Up The Pieces)

|

| Severe weather reports from 2012 Derecho |

Adding to the misery, the region remained under an EHE (Extreme Heat Event) advisory for the next two weeks resulting in dozens of heat-related deaths. The following year the CDC's MMWR released a report on Heat-Related Deaths during this event.

(Excerpt)

This report describes 32 heat-related deaths in Maryland, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virginia that occurred during the 2 weeks following the storms and power outages. Median age of the decedents was 65 years, and most of the excessive heat exposures occurred within homes.

We are now a month into hurricane season, and NOAA has issued an aggressive forecast (see NOAA's Busy 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook), meaning that many of us could face extended power outages this summer.

Eight years later, a heat wave across the central and eastern part of the nation killed as many as 7,500 people (cite). More recently, in 1999, a prolonged heat wave along the Eastern seaboard is believed to have killed 500 (cite).

July is normally the hottest month of the year in the United States, and this year could set records. NOAA has released their 30-day heat/precipitation forecasts for July (see chart below), and it predicts most of the country can expect above average temperatures.

With this weekend's forecast in mind, some timely advice from the CDC's EXTREME HEAT website. Follow the link to learn to learn how to prepare for, and respond to, extreme heat events.

Having sweltered-in-place following hurricanes and other summer power outages, I've take some aggressive preparedness steps, including having plenty of water stockpiled, and creating some `cooling' options for when the power is out.

For me, the easiest, and least expensive option was to buy one or more solar powered USB batteries (see below) and a USB powered fan.

|

| Battery, Solar Panel, Fan & Light - About $50. |

(Note: Newer products now have 20,000 and 25,000 milliamp batteries and larger (4 fold) solar panels)

While limited in terms of what they can power (and for how long), these setups are ideal for those who need a light weight bug-out friendly solution, or for anyone who isn't comfortable with creating more complex systems. For more on solar power solutions, you may wish to revisit My New (And Improved) Solar Battery Project (for CPAP) and My New Solar Power System (Updated For 2020)).

As we discussed a few weeks ago, in Why Preparing For This Year's Hurricane Season Will Be `Different', our concurrent COVID-19 pandemic adds an extra layer of difficulty to nearly everything, and we need to plan accordingly.

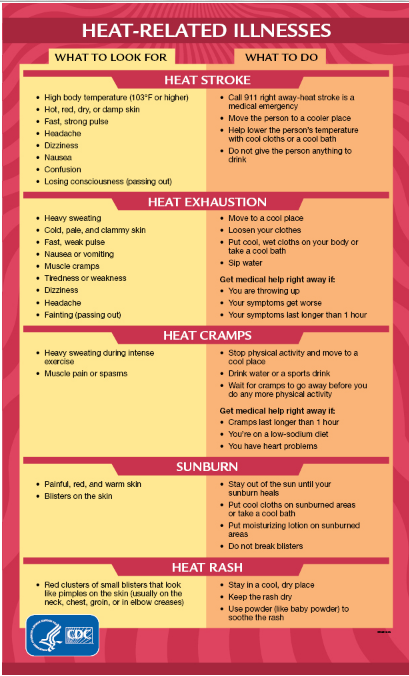

For some advice on recognizing heat-related illnesses, and what to do about them, the CDC provides the following guidance.