GAO: A Herd Immunity For COVID-19 Primer

Many governments, eager to reassure a worried public, touted the notion that once 65%-75% of the public had been exposed to the virus the `pandemic phase' would end. And some even hinted that might only be a few months months away.

The flaw in this ointment - which we discussed at length in COVID-19: From Here To Immunity - was that this assumed that there we're a large number of moderate, mild, or asymptomatic infections that we didn't see, and that once you were infected - even asymptomatically - you acquired long-lasting immunity.

But in 2016 a study (see EID Journal: Antibody Response & Disease Severity In HCW MERS Survivors) that tested 9 Health care workers who were infected with MERS during the 2014 Jeddah outbreak (2 severe pneumonia, 3 milder pneumonia, 1 URTI, and 3 asymptomatic),found only those with severe pneumonia still carried detectable levels of antibodies 18 months later.

Similarly, in Fenner and White's Medical Virology (Fifth Edition - 2017), the authors describe the clinical features of seasonal human coronaviruses (hCoVs) in Chapter 31:

The typical coronavirus “common cold” is mild and the virus remains localized to the epithelium of the upper respiratory tract and elicits a poor immune response, hence the high rate of reinfection. There is no cross-immunity between human coronavirus-229E and human coronavirus-OC43, and it is likely that new strains are continually arising by mutation selection.By late summer of 2020 we were beginning to see evidence of reinfections - long before the first of the new variants (Alpha, Delta, Omicron, etc.) began to appear - leading to the following statement (see

CDC Clarifies: Recovered COVID-19 Cases Are Not Necessarily Immune To Reinfection).

The initial high degree of protection offered by COVID vaccines provided a badly needed boost to the idea of achieving `herd immunity', but within a year the arrival of 3 distinct classes of variants (Alpha, Delta, and Omicron) had severely eroded the vaccine's effectiveness.

While vaccines still provide significant reductions in severe illness, hospitalizations, and deaths from COVID, they provide only limited protection against reinfection. Similarly, protection offered by previous COVID infection wanes over time, and is further eroded when new variants are introduced.

Which is why - even though Omicron has spread widely across the nation over the past 5 months and increased the number of people with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies to an estimated 58% - we can't assume that most of us are now `immune' to the virus.

Particularly with new variants constantly emerging.

The development of more cross-protective, and longer lasting COVID vaccines - or the emergence of a more `stable' SARS-CoV-2 virus - could someday still lead us to something approaching herd immunity.

But for the foreseeable future, getting the COVID vaccine - and staying current with your`booster' shots - likely provides the best available protection.

Weekly / April 26, 2022 / 71(17)

Kristie E.N. Clarke, MD1; Jefferson M. Jones, MD1; Yangyang Deng, MS2; Elise Nycz, MHS1; Adam Lee, MS2; Ronaldo Iachan, PhD2; Adi V. Gundlapalli, MD, PhD1; Aron J. Hall, DVM1; Adam MacNeil, PhD1

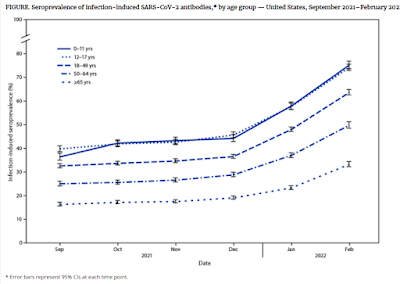

In December 2021, the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, became predominant in the United States. Subsequently, national COVID-19 case rates peaked at their highest recorded levels.* Traditional methods of disease surveillance do not capture all COVID-19 cases because some are asymptomatic, not diagnosed, or not reported; therefore, the proportion of the population with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (i.e., seroprevalence) can improve understanding of population-level incidence of COVID-19. This report uses data from CDC’s national commercial laboratory seroprevalence study and the 2018 American Community Survey to examine U.S. trends in infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence during September 2021–February 2022, by age group.

The national commercial laboratory seroprevalence study is a repeated, cross-sectional, national survey that estimates the proportion of the population in 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico that has infection-induced antibodies to SARS-CoV-2.† Sera are tested for anti-nucleocapsid (anti-N) antibodies, which are produced in response to infection but are not produced in response to COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized for emergency use or approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.§

During September 2021–February 2022, a convenience sample of blood specimens submitted for clinical testing was analyzed every 4 weeks for anti-N antibodies; in February 2022, the sampling period was <2 weeks in 18 of the 52 jurisdictions, and specimens were unavailable from two jurisdictions. Specimens for which SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing was ordered by the clinician were excluded to reduce selection bias. During September 2021–January 2022, the median sample size per 4-week period was 73,869 (range = 64,969–81,468); the sample size for February 2022 was 45,810. Seroprevalence estimates were assessed by 4-week periods overall and by age group (0–11, 12–17, 18–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years). To produce estimates, investigators weighted jurisdiction-level results to population using raking across age, sex, and metropolitan status dimensions from 2018 American Community Survey data¶ (1). CIs were calculated using bootstrap resampling (2); statistical differences were assessed by nonoverlapping CIs. All specimens were tested by the Roche Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 pan-immunoglobulin immunoassay.** All statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.0.3; The R Foundation). This activity was reviewed by CDC, approved by respective institutional review boards, and conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.††

During September–December 2021, overall seroprevalence increased by 0.9–1.9 percentage points per 4-week period. During December 2021–February 2022, overall U.S. seroprevalence increased from 33.5% (95% CI = 33.1–34.0) to 57.7% (95% CI = 57.1–58.3). Over the same period, seroprevalence increased from 44.2% (95% CI = 42.8–45.8) to 75.2% (95% CI = 73.6–76.8) among children aged 0–11 years and from 45.6% (95% CI = 44.4–46.9) to 74.2% (95% CI = 72.8–75.5) among persons aged 12–17 years (Figure). Seroprevalence increased from 36.5% (95% CI = 35.7–37.4) to 63.7% (95% CI = 62.5–64.8) among adults aged 18–49 years, 28.8% (95% CI = 27.9–29.8) to 49.8% (95% CI = 48.5–51.3) among those aged 50–64 years, and from 19.1% (95% CI = 18.4–19.8) to 33.2% (95% CI = 32.2–34.3) among those aged ≥65 years.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, convenience sampling might limit generalizability. Second, lack of race and ethnicity data precluded weighting for these variables. Third, all samples were obtained for clinical testing and might overrepresent persons with greater health care access or who more frequently seek care. Finally, these findings might underestimate the cumulative number of SARS-CoV-2 infections because infections after vaccination might result in lower anti-N titers,§§,¶¶ and anti-N seroprevalence cannot account for reinfections.

As of February 2022, approximately 75% of children and adolescents had serologic evidence of previous infection with SARS-CoV-2, with approximately one third becoming newly seropositive since December 2021. The greatest increases in seroprevalence during September 2021–February 2022, occurred in the age groups with the lowest vaccination coverage; the proportion of the U.S. population fully vaccinated by April 2022 increased with age (5–11, 28%; 12–17, 59%; 18–49, 69%; 50–64, 80%; and ≥65 years, 90%).*** Lower seroprevalence among adults aged ≥65 years, who are at greater risk for severe illness from COVID-19, might also be related to the increased use of additional precautions with increasing age (3).

These findings illustrate a high infection rate for the Omicron variant, especially among children. Seropositivity for anti-N antibodies should not be interpreted as protection from future infection. Vaccination remains the safest strategy for preventing complications from SARS-CoV-2 infection, including hospitalization among children and adults (4,5). COVID-19 vaccination following infection provides additional protection against severe disease and hospitalization (6). Staying up to date††† with vaccination is recommended for all eligible persons, including those with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.