#16,828

In September of 2021, in Wyoming DOH Reports A Rare Case Of Pneumonic Plague, we looked at an unusual report of Pneumonic Plague in the western United States, contracted by a patient who had close contact with sick pet cats.

While unusual, Plague in the United States isn't unheard of, at least in states west of the Mississippi (see map below).

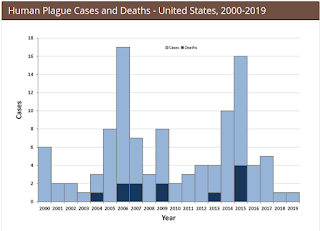

The last major urban outbreak of plague in the United States occurred in 1924-25 in Los Angeles. Since then, only scattered cases have been reported, with about 7-15 cases - mostly of bubonic variety - reported each year in the U.S.

Plague can present in three forms: bubonic, septicemic and pneumonic. If untreated, bubonic plague can evolve to a more transmissible pneumonic plague.

- Bubonic Plague (Yersinia Pestis) - carried by rats, squirrels, and other small rodents, and transmitted by fleas - sets up in the lymphatic system, resulting in the tell-tale buboes, or swollen lymph glands in the the groin, armpits, and neck.

- Less commonly Pneumonic Plague may develop, when the infected individual develops a severe pneumonia, with coughing and hemoptysis (expectoration of blood), which may spread the disease by droplets from human-to-human.

Plague - at least in countries with modern medicine - doesn't carry the same dread it once did. If diagnosed early, antibiotic treatment is often quite successful.

But when a patient presents with acute respiratory symptoms in the middle of a raging COVID pandemic, pneumonic plague doesn't rank very high on any clinician's differential diagnosis list.

Which brings us to a Notes From The Field report in this week's MMWR that chronicles the presentation, treatment, and eventual diagnosis, and recovery of a pneumonic plague case against the backdrop of our COVID pandemic.

This is a fascinating report that reminds us that sometimes when we hear hoof beats, it really is a zebra. I'll have more after the break.

Notes from the Field: Diagnosis and Investigation of Pneumonic Plague During a Respiratory Disease Pandemic — Wyoming, 2021

Weekly / June 17, 2022 / 71(24);806–807

Allison W. Siu, DVM1; Courtney Tillman, MPH2; Clay Van Houten, MS2; Ashley Busacker, PhD2,3; Alexia Harrist, MD2

In September 2021, the Wyoming Department of Health (WDH) was notified of a suspected case of pneumonic plague in an adult who was admitted to a Wyoming hospital following a 48-hour history of worsening cough, dyspnea, and acute onset of hemoptysis. The patient reported no recent travel history or ill contacts but noted interacting with two pet cats that were ill. Health care providers initially suspected COVID-19 because of compatible symptoms, no history of COVID-19 vaccination, and increased SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) community transmission in Wyoming during this period.

Approximately 48 hours after symptom onset, the patient received a negative SARS-CoV-2 antigen test result at a provider’s office. The patient was hospitalized later that day for worsening symptoms and received two negative SARS-CoV-2 laboratory-based nucleic acid amplification test results. Lung imaging was consistent with community-acquired pneumonia. Respiratory specimens tested negative for common viral pathogens on a respiratory panel. Within 48 hours of admission, the patient required mechanical ventilation and developed sepsis.

The patient was treated for pneumonia and sepsis with azithromycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and vancomycin. Seventy-two hours after the patient was admitted to the hospital, blood and sputum cultures did not indicate a causative pathogen. Because of the patient’s history of exposure to cats that were ill, an infectious diseases specialist recommended repeating a sputum culture with Gram stain and empiric treatment with ciprofloxacin. Gram-negative bacilli were detected, and the Wyoming Public Health Laboratory subsequently confirmed Yersinia pestis as the pathogen.

WDH immediately conducted interviews to determine exposure source, identify close contacts requiring postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) (1), and guide public health prevention measures. Interviews with veterinary clinic staff members and review of records revealed that one cat had died from an undiagnosed severe illness after onset of respiratory symptoms; serologic testing of specimens from the surviving cat for Y. pestis by CDC was negative. WDH interviews with local animal control and state wildlife officials revealed no known epizootic near the patient’s residence, which was in a rural area of Wyoming; however, both pet cats were known to spend time indoors and outdoors and were not treated with flea control products.

To guide PEP recommendations, WDH reviewed medical records, collaborated with hospital infection preventionists, and interviewed the patient’s friends, family members, neighbors, and work colleagues. Twenty-two close contacts were identified (19 health care workers and three personal contacts). All received PEP within 1 week of the patient’s symptom onset, and none developed illness. The patient recovered and was discharged 35 days after hospital admission.

Environmental assessment of the patient’s residence was conducted by a professional pest management company. Plague prevention measures included flea mitigation and rodent habitat elimination to reduce abundance of potential flea-harboring rodents. WDH shared plague prevention materials by press release and disseminated educational materials to community members.

Y. pestis is reportable in Wyoming (2) and is endemic in rodents and their fleas statewide. Persons can become infected through the bite of an infected flea or contact with infected animals including pets (3), underscoring the importance of year-round flea control for pets. Pneumonic plague is the only clinical form of the disease that can be transmitted between persons through respiratory droplets and if left untreated is almost always fatal (1). This is the second case of primary pneumonic plague and the seventh of any form of plague in Wyoming’s documented history. Nationwide, 18 cases of pneumonic plague were reported during 1942–2018 (4).

Rapid identification and diagnosis of Y. pestis is crucial for effective patient treatment and public health response. Despite the delay in diagnosis, WDH was able to rapidly coordinate timely public health intervention and effective community outreach. Furthermore, recognition of patient contact with cats that were ill was critical in prompting change to first-line antibiotic treatment effective against plague. Exposure to infected cats is a substantial plague risk in the United States (5), highlighting the importance of animal contact history during patient intake.

Overlooked diagnoses of rare pathogens can lead to significant consequences. This investigation highlights challenges associated with diagnosis and treatment of an illness from a rare pathogen whose symptoms mimic those of a pandemic illness, in this case, COVID-19. Timelier diagnosis might have resulted in initiation of effective antibiotic treatment closer to disease onset and decreased illness severity and hospitalization. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of plague in patients with compatible symptoms and exposure history in areas where plague is endemic.

Even during non-pandemic years - CAP, or Community Acquired Pneumonia - is responsible for about 1 million hospitalizations and 50,000 deaths in the United States. Somewhat surprisingly, the causative agent often goes unidentified, although viral infections appear to out-number bacterial infections by roughly 2:1.

In 2010, the CDC began their 5-year EPIC Study (Etiology Of Pneumonia In the Community), and despite modern laboratory analysis, in the majority (62%) of cases no definitive pathogenic agent was ever identified.

Luckily, empiric antibiotic treatment guidelines for pneumonia cover a lot of bases, and generally work quite well, but are not recommended for a suspected viral pneumonia, like COVID-19.

The advent of effective antibiotics makes plague far less fearsome than it once was, but Madagascar's recent epidemics, and a large 1994 India outbreak that infected more than 5,000 people (see WHO Summary), show that large urban outbreaks are still possible.

In 2019's CDC: The 8 Zoonotic Diseases Of Most Concern In The United States, we looked at a joint CDC, USDA, DOI report on the top (n=56) zoonotic diseases of national concern for the United States.

While Zoonotic Influenzas (avian, swine, etc.) were at the top of the list, Plague ranked 4th, and novel coronaviruses (MERS, SARS, etc.) ranked 5th.

I confess to having a particular interest in Plague, which stems from my working as a paramedic in Phoenix, Arizona where Bubonic plague cases are still occasionally found, and my reading – around the age of 11 – of James Leasor’s The Plague and The Fire which recounts two incredible years in London’s history (1665-1666) - which began with the Great plague, and ended with the Fire of London.

A fascinating read (if you can find a copy) for both history and epidemic aficionados.