#17,375

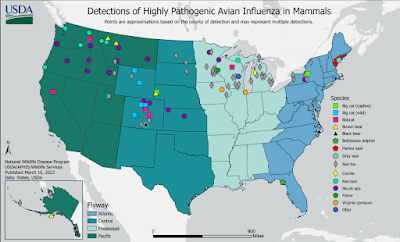

As the USDA map above (updated 3/16/23) shows, there have been nearly 150 documented spillovers of HPAI to mammalian wildlife in the United States, but it is expected that many more mammalian deaths have occurred due to the virus.

Why nearly all of the reports to date have come from northern states isn't clear, although it may come down to differences in climate and terrain (swamps vs. forests vs. deserts), and the fact that some states may be looking harder than others.Mammals often die in remote and difficult to access places where their carcasses are quickly scavenged by other animals, meaning they are never discovered or tested.

Late yesterday, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) released the following information on the detection of HPAI H5N1 in two deceased (and related) mountain lions.

First the press release detailing their findings, after which I'll return with more.

Avian Influenza Detected In Deceased Mountain Lions

March 28, 2023

The Eurasian strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI H5N1) was detected in two mountain lions in Mono County in December 2022 and January 2023, according to wildlife health experts with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). While additional disease testing is being conducted to rule out the possibility of co-infections, HPAI H5N1 is suspected to be the cause of the death for both mountain lions.

This is the second species of wild mammal known to have contracted HPAI H5N1 in California since the virus was reported in wild birds in July 2022. In January, the virus was detected in a bobcat found in Butte County.

The new findings also mark the first detection of HPAI H5N1 in Mono County. To date, the virus has been found in 45 counties statewide.

“The Eurasian lineage of avian influenza is primarily a disease impacting birds but is occasionally being detected in wild mammals. We don’t expect this to have a population-level impact for California’s mountain lions or other mammalian carnivores, but it is a disease we will continue to monitor,” said Dr. Jaime Rudd, a pesticide and disease investigations specialist in CDFW’s Wildlife Health Lab.

“The main route of disease transmission for carnivores seems to be through ingestion of infected birds – typically waterfowl such as geese. Biologists following the movements of these mountain lions noted that they had preyed upon wild Canada geese in the past,” Rudd said.

Remains of the two mountain lions, who were related (mother and daughter), were collected from Mono Lake in Mono County on December 23 and January 14. Samples were submitted to the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory in Davis for preliminary testing. Last week, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Veterinary Services Laboratories confirmed the detection of HPAI H5N1.

“The main pathological finding for these two mountain lions was encephalitis, which is inflammation of the brain. Additionally, there were lesions in the lungs causing pulmonary edema. Much of the lesions in the brain and lungs were associated with the virus, but additional disease testing is being performed to rule out the possibility of co-infection,” said Rudd.

Of note is that both mountain lions were wearing GPS collars as part of a CDFW population study. The mortality notification sent from the collar helped biologists track the deceased animals and allowed for their remains to be collected in a timely manner to perform necropsies and determine cause of death.

“HPAI H5N1 is still considered a low-risk zoonotic pathogen,” said CDFW Senior Wildlife Veterinarian Dr. Deana Clifford. “It’s significant that the detections occurred far from the bobcat detection, and in an area where the disease had not yet been detected in wild birds. This means it’s possible that the mountain lions may represent detections of a new foci of infections for wild birds.”

Notwithstanding the mountain lion and bobcat detections, infection of wild mammals with avian influenza viruses appears to be relatively rare. Elsewhere in the U.S. and Canada, periodic detections of HPAI H5N1 have been made in mammalian carnivores including foxes, bobcats, raccoons, skunks and bears. Detections in mountain lions have occurred in five other states. The virus has also been detected in a small number of marine mammals.

The strain of HPAI H5N1 currently circulating in the U.S. and Canada has caused illness and death in a higher diversity of wild bird species than during previous avian influenza outbreaks, affecting raptors and avian scavengers such as turkey vultures and ravens. Mammalian and avian predators and scavengers may be exposed to avian influenza viruses when feeding on infected birds.

An informational flyer addressing frequently asked questions about avian influenza is available on CDFW’s website. Currently, the Centers for Disease Control(opens in new tab) considers the transmission risk of avian influenza to people to be low, but recommends taking basic protective measures (i.e., wearing gloves and face masks and handwashing) if contact with wildlife cannot be avoided. CDFW does not recommend people handle or house sick wildlife.

Practicing biosecurity is the most effective way to keep people, domestic poultry and pets healthy. Please visit the CDFA(opens in new tab) and USDA(opens in new tab) websites for biosecurity information. Please report sick or dead poultry and pet birds to the CDFA hotline at (866) 922-2473.

CDFW’s Wildlife Health Laboratory, in coordination with partners, continues to monitor wildlife for signs of illness and investigate mortality events. The public is encouraged to report dead wildlife using CDFW’s mortality reporting form. For non-urgent questions concerning wildlife, please contact your local CDFW Regional Office or your local animal control service.

Media contact:

Ken Paglia, CDFW Communications, (916) 825-7120

While the CDFW reassures that `. . . infection of wild mammals with avian influenza viruses appears to be relatively rare . . . ', each spillover into a non-avian species is another opportunity for the virus to better adapt to a mammalian host.

Also of concern, H5N1 appears to be becoming increasingly neurotropic in mammals.

This month alone, we've looked at several studies that have documented profound neurological manifestations in infected mammals, including:

UK Reports 2 Dolphins With HPAI H5N1 & EID Report On Infected Harbor Porpoise in Sweden

PLoS Pathogens: Evolution of Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Influenza A Virus in the Central Nervous System of Ferrets

While we've seen reports in the past suggesting that H5N1 (and even seasonal influenza) could produce severe neurological manifestations, it was always thought to be more the exception than the rule.

Tthere were anecdotal reports from Vietnam and Indonesia, but it wasn't until 2015 that we got our first detailed look (with MRI imaging and extensive histological analysis) of a fatal Neurotropic H5N1 Infection in a Nurse in Canada who recently returned from a visit to China.

The authors of that study warned:

These reports suggest the H5N1 virus is becoming more neurologically virulent and adapting to mammals. Despite the trend in virulence, the mode of influenza virus transmission remains elusive to date. It is unclear how our patient acquired the H5N1 influenza virus because she did not have any known contact with animals or poultry.

While the future course and impact of H5N1 in humans is still very much up in the air, we've seen ample evidence that cats and dogs are susceptible to HPAI H5 (see 2015's HPAI H5: Catch As Cats Can and 2010's Study: Dogs And H5N1).

Since the majority of wildlife detections of H5N1 have come from peridomestic animals in urban or suburban settings, it makes sense to protect your cat and dog when they are outside.

While the risks are still probably low, they are not zero. The CDC has some advice on keeping your pets, and yourself, safe from the virus. With the spring return migration now underway, and millions of birds headed north, a little extra caution is probably wise.

If your domestic animals (e.g., cats or dogs) go outside and could potentially eat or be exposed to sick or dead birds infected with bird flu viruses, or an environment contaminated with bird flu virus, they could become infected with bird flu. While it’s unlikely that you would get sick with bird flu through direct contact with your infected pet, it is possible. For example, in 2016, the spread of bird flu from a cat to a person was reported in NYC. The person who was infected [2.29 MB, 4 pages] was a veterinarian who had mild flu symptoms after prolonged exposure to sick cats without using personal protective equipment.

If your pet is showing signs of illness compatible with bird flu virus infection and has been exposed to infected (sick or dead) wild birds/poultry, you should monitor your health for signs of fever or infection.

Take precautions to prevent the spread of bird flu.

As a general precaution, people should avoid direct contact with wild birds and observe wild birds only from a distance, whenever possible. People should also avoid contact between their pets (e.g., pet birds, dogs and cats) with wild birds. Don’t touch sick or dead birds, their feces or litter, or any surface or water source (e.g., ponds, waterers, buckets, pans, troughs) that might be contaminated with their saliva, feces, or any other bodily fluids without wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). More information about specific precautions to take for preventing the spread of bird flu viruses between animals and people is available at Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu Viruses in People. Additional information about the appropriate PPE to wear is available at Backyard Flock Owners: Take Steps to Protect Yourself from Avian Influenza.