#17,352

While we've seen hundreds of reports of terrestrial mammals infected with HPAI H5N1, thousands of sea lions and seals have been killed by this emerging strain of avian flu. Earlier today we saw a report on 330 seals in Maine affected, and Peru (at last count) had lost nearly 3,500 sea lions to the virus.

While far less common, we've also seen reports of H5N1 infections in dolphins and porpoises (both cetaceans) in North America and in Europe (see reports from Florida, Canada, and Sweden).

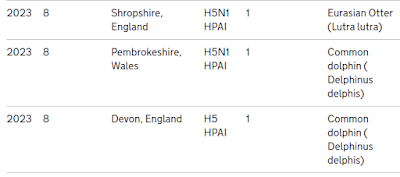

The UK's APHA (Animal & Plant Health Agency), along with DEFRA (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs) maintains a list of mammals that have tested positive for HPAI H5N1.

For week 8 of 2023, they are reporting that two dolphins and an otter have tested positive for the virus.

Previously the UK has reported on 9 seals, and 4 otters infected with H5N1, but these are the first two dolphins on record. It is likely, however, that many marine (and terrestrial) mammals get infected, and died or recovered, without being detected.

This week we also have an EID report on the porpoise infected with H5N1 from Sweden, which we covered in some detail last August in Sweden: First Known Infection of A Porpoise With Avian H5N1.

As we've seen in so many other reports (see here, here, here, and here) on severe neurological damage in mammals, histological findings suggest that H5N1 is neurotropic in cetaceans as well.

I've only posted some excerpts from a longer report, so follow the link to read it in its entirety.

Research Letter

Elina Thorsson, Siamak Zohari, Anna Roos, Fereshteh Banihashem, Caroline Bröjer, and Aleksija Neimanis

Abstract

We found highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus clade 2.3.4.4b associated with meningoencephalitis in a stranded harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena). The virus was closely related to strains responsible for a concurrent avian influenza outbreak in wild birds. This case highlights the potential risk for virus spillover to mammalian hosts.

Europe and, more recently, North America are experiencing unprecedented mortality in wild and domestic birds because of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus clade 2.3.4.4b (1). Infections in tens of thousands of wild birds representing at least 112 species, including large numbers of seabirds, have been documented (1,2). Since December 2021, HPAI H5N1 has dominated infections in wild birds in Sweden, other countries in Europe, and North America, and it has occasionally spilled over into wild mammals, such as red foxes and mustelids (1).

Recently, increased mortality in harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) and gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) in eastern North America has been associated with HPAI H5N1 infection (3). Although influenza A virus (IAV) infections in seals have been repeatedly documented, reports in cetaceans are scarce (4). We are aware of only 2 cases where IAV in a cetacean might have been associated with disease (4,5). We report HPAI H5N1 infection in a harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) in Sweden.

In late June 2022, an immature male harbor porpoise became stranded in shallow water off the west coast of Sweden (58.64817 N, 11.28973 E). It swam in circles, was unable to right itself, and drowned shortly after discovery. The carcass was stored frozen until necropsy examination at the National Veterinary Institute (Uppsala, Sweden). Macroscopic findings were minimal and included pulmonary edema consistent with drowning.

Microscopically, we detected moderate lymphoplasmacytic meningoencephalitis with neuronal necrosis, gliosis, perivascular cuffing, and vasculitis in the brain (Figure 1, panel A). The lung contained few areas of mild, mononuclear septal thickening and increased numbers of alveolar macrophages.

(SNIP)

Although the genome of the detected HPAI H5N1 virus did not contain any known genetic marker of mammal adaptation, the clinical manifestations and presence of virus in diverse organs, including the brain, indicate the potential risk of HPAI viruses to mammalian hosts even without adaptation. This risk is a consideration for persons in close contact with infected animals. In addition, extensive circulation of the HPAI H5Nx virus clade 2.3.4.4b in wild and domestic bird populations and sporadic transmission to humans and other mammals enables the virus to evolve, increasing the risk of it becoming more transmissible or pathogenic for mammals.

Understanding the epidemiology and host–pathogen environmental ecology of IAVs among wildlife, coupled with continuous surveillance, developing better tools for risk assessments, and updating public and animal health countermeasures and intervention strategies, are essential for reducing the threats of zoonotic influenza.

Dr. Thorsson is a wildlife pathologist at the National Veterinary Institute and a resident of the European College of Veterinary Medicine, Wildlife Population Health. Her primary research interests are veterinary pathology, infectious diseases of wildlife, and wildlife population health.