Maine: Seal Deaths Linked To Avian H5N1

We've known for decades that marine mammals are susceptible to influenza (see below).

- During the winter of 1979-1980 seals were found suffering from pneumonia on the Cape Cod. In that instance, the culprit turned out to be an H7N7 influenza. (see Isolation of an influenza A virus from seals G. Lang, A. Gagnon and J. R. Geraci)

- In 1984 avian H4N5 – a strain previously only seen in birds – was determined to be behind the deaths of a number of New England seals in 1982 and 1983 (cite Are seals frequently infected with avian influenza viruses? R G Webster et al.)

- In 1995, in the Journal of General Virology, authors R. J. Callan, G. Early, H. Kida and V. S. Hinshaw wrote of the The appearance of H3 influenza viruses in seals during the early 1990s. Seals have also been shown susceptible to influenza B (cite Influenza B virus in seals. Osterhaus AD, Fouchier , et al.).

And over the past decade - as avian influenza has increased it geographic range - we've seen an increasing number of seal die offs from the virus.

- In 2014, as many as 3,000 harbor seals reportedly died from avian H10N7 (see Avian H10N7 Linked To Dead European Seals), prompting warnings to the public not to touch seals.

- In 2017, HPAI H5N8 (clade 2.3.4.4.B) was found in Grey seals in the Baltic Sea (see EID Journal: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N8) Virus in Gray Seals, Baltic Sea).

- Reports continued into 2021 (see Two Reports On HPAI H5N8 Infecting Marine Mammals (Denmark & Germany and H5N1 in seals in Sweden and the UK).

- In recent months Peru has reported 3,500 Sea Lions Killed By H5N1 Avian Flu, reports are starting to filter in from Chile, and there is an (unconfirmed) report of 2,500 seals killed in Dagestan, along with scattered reports of dolphins and porpoises infected with the virus.

“It's not surprising that you might have transmission between the seals, because it has happened with low pathogenic avian influenza,” said Puryear. “However, we can't say definitively whether or not there has been mammal-to-mammal transmission of HPAI.”

Researchers have not detected avian flu in a New England seal since the end of last summer, but they will on the alert for any new signals this summer.

Dispatch

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Outbreak in New England Seals, United States

Wendy Puryear, Kaitlin Sawatzki, Nichola Hill, Alexa Foss, Jonathon J. Stone, Lynda Doughty, Dominique Walk, Katie Gilbert, Maureen Murray, Elena Cox, Priya Patel, Zak Mertz, Stephanie Ellis, Jennifer Taylor, Deborah Fauquier, Ainsley Smith, Robert A. DiGiovanni, Adriana van de Guchte, Ana Silvia Gonzalez-Reiche, Zain Khalil, Harm van Bakel, Mia K. Torchetti, Kristina Lantz, Julianna B. Lenoch, and Jonathan Runstadler

Abstract

We report the spillover of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) into marine mammals in the northeastern United States, coincident with H5N1 in sympatric wild birds. Our data indicate monitoring both wild coastal birds and marine mammals will be critical to determine pandemic potential of influenza A viruses.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses are of concern because of their pandemic potential, socioeconomic impact during agricultural outbreaks, and risks to wildlife conservation. Since October 2020, HPAI A(H5N1) virus, belonging to the goose/Guangdong H5 2.3.4.4b clade, has been responsible for >70 million poultry deaths and >100 discrete infections in many wild mesocarnivore species (1). As of January 2023, H5N1 infections in mammals have been primarily attributed to consuming infected prey, without evidence of further transmission among mammals.

We report an HPAI A(H5N1) virus outbreak among New England harbor and gray seals that was concurrent with a wave of avian infections in the region, resulting in a seal unusual mortality event (UME); evidence of mammal adaptation existed in a small subset of seals. Harbor (Phoca vitulina) and gray (Halichoerus grypus) seals in the North Atlantic are known to be affected by avian influenza A virus and have experienced previous outbreaks involving seal-to-seal transmission (2–7). Those seal species represent a pathway for adaptation of avian influenza A virus to mammal hosts that is a recurring event in nature and has implications for human health.

(SNIP)

Conclusions

Transmission from wild birds to seals was evident for >2 distinct HPAI H5N1 lineages in this investigation and likely occurred through environmental transmission of shed virus. Viruses were not likely acquired by seals through predation or scavenging of infected animals, because birds are not a typical food source for harbor or gray seals (13). Data do not support seal-to-seal transmission as a primary route of infection. If individual bird–seal spillover events represent the primary transmission route, the associated seal UME suggests that transmission occurred frequently and had a low seal species barrier. We observed novel amino acid changes throughout the virus genome in seals, including amino acid substitutions associated with mammal adaptation.

In contrast to outbreaks in agricultural settings, outbreaks of HPAI in wild populations can rarely be managed well through biosecurity measures or depopulation, which is particularly true for large, mobile marine species such as seals. Avian and mammalian colonial wildlife might be particularly affected by influenza A viruses, which could enable ongoing circulation between and within species, providing opportunities for reassortments of novel strains and study of mammalian virus adaptation. Migratory animals might further disseminate the viruses over broad geographic regions. Therefore, the interface of wild coastal birds and marine mammals is critical for monitoring the pandemic potential of influenza A viruses.

Dr. Puryear is a virologist at The Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University in the Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health. Her research interests focus on epidemiology, evolution, and adaptation of wildlife diseases.

NEWS RELEASE 15-MAR-2023

Bird flu associated with hundreds of seal deaths in New England in 2022, Tufts researchers find

A new study from Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine is the first to connect highly pathogenic avian influenza to a large scale mortality event in wild mammals

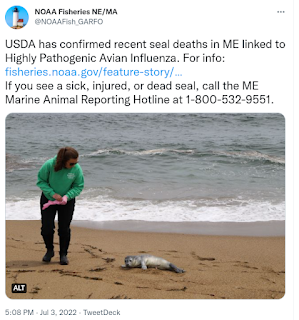

Researchers at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University found that an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) was associated with the deaths of more than 330 New England harbor and gray seals along the North Atlantic coast in June and July 2022, and the outbreak was connected to a wave of avian influenza in birds in the region.

The study was published on March 15 in the journal Emerging Infectious Disease.