Spillover of HPAI H5N1 In United States - Credit USDA

#17,168

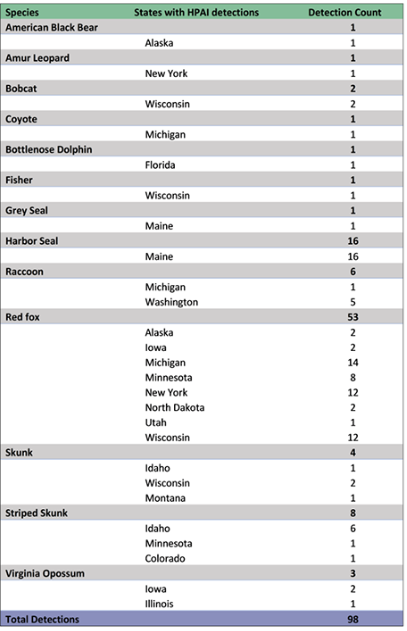

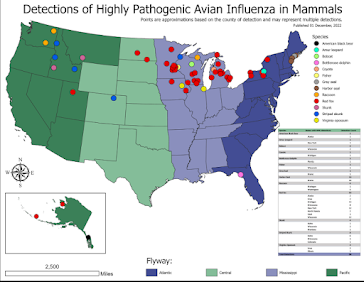

Although primarily a disease infecting birds, we continue to see reports of HPAI H5N1 infecting both land and marine mammals, with the United States alone reporting nearly 100 such cases (see USDA data).

Surveillance and testing of sick or dead wildlife is sketchy at best, and we undoubtedly only know about a small percentage of infections in the wild. The USDA's list of species affected (below) is far from complete, and continues to expand.

While spillovers to terrestrial mammals are most common (and easiest to find), infections in Grey and Harbor seals are often reported, both in the United States and in Canada (see Quebec: Seal Deaths Linked To Avian H5N1), and Florida has reported a single death in a bottle-nosed dolphin.

Human infections with this clade of HPAI H5N1 have thankfully remained very few and very mild. But the same cannot be said for many of the recent wildlife infections we've seen (see here, here, here, and here), which often involve systemic spread of the virus and severe (usually fatal) neurological manifestations.Similar reports have been received from Europe (see Sweden: First Known Infection of A Porpoise With Avian H5N1), and we recently saw reports that Peru was investigating the deaths of sea lions on beaches where H5N1 was found.

Thirty days ago, in Preprint: Rapid Evolution of A(H5N1) Influenza Viruses After Intercontinental Spread to North America, we saw how quickly HPAI H5N1 began to mutate, and diversify, after it arrived in the Untied States, and that different strains possessed different levels of pathogenicity.

Another species of mammal susceptible to the H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus: first case in a white-sided dolphin

Photo Credit: Atlantic white-sided dolphins by batwrangler via Flicker

BY CAROLYN BLUSHKE · 2022-12-12

Here we report a case of fatal infection with the highly pathogenic H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus (AIV H5N1) in a white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus). This juvenile male dolphin was found dead stranded on September 5 on a beach near Rimouski (Quebec). The carcass was submitted by the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (RQUMM) to the CWHC – Quebec regional centre for analysis.

The animal was in good body condition, which is suggestive of death from an acute event. Apart from the presence of low intensity parasitic infections, no macroscopic lesion was observed in the animal. Histopathological examination of the tissues revealed the presence of inflammatory and necrotic lesions in the liver, lymph nodes and spleen. Acute inflammatory lesions were also present in the lungs (pneumonia) and brain (very mild encephalitis). Molecular analyzes carried out by the laboratory of the Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec have revealed the presence of an AIV H5N1) in the brain. This result was confirmed by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency laboratory. The results of these examinations indicate that this dolphin died following an acute infection with an AIV H5N1 virus.

Although AIV H5N1 viruses primarily affect birds, several species of mammals are also known to be susceptible. In marine mammals, infections by this virus have been documented mainly in harbour seals, but cases in a few gray seals were also reported. Until recently, no case of fatal infection by an avian influenza virus had been documented in cetaceans (whales and dolphins). To our knowledge, only two cases of AIV H5N1 infection have been reported in cetaceans so far, one case in a bottlenose dolphin in Florida and one case in a harbour porpoise in Sweden. The case presented here, which would therefore be the first case of infection by this virus in a white-sided dolphin, indicates that this species is susceptible to this emerging virus in North America.

The data collected by the RQUMM does not seem to indicate an increase in white-sided dolphin mortality in the St. Lawrence Estuary this summer, despite the presence of an epidemic among harbour seals. This suggests that there has been no transmission of this virus between dolphins and therefore the number of cases should be limited; contact between dolphins and infected birds is probably infrequent.

Although the risk of transmission of this influenza virus to humans and domestic animals seems low, it is recommended not to approach, and especially not to touch, sick or dead marine mammals. Contact between our pets and dead wild animals should also be prevented.

Stéphane Lair – CWHC Quebec / CQSAS, Faculté de médecine vétérinaire, Université de Montréal

While previous incarnations of HPAI H5N1 have loomed large before - only to lose steam and recede - we can't count on our luck holding forever.

Clade 2.3.4.4b continues to evolve, and has become more widespread - and better adapted to year-round persistence (see Study: Global Dissemination of Avian H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Viruses and Biologic Analysis Of Chinese Variants) - making it a more pervasive threat than we've seen previously.

How this plays out is anyone's guess. But we need to be prepared to deal with new challenges ahead.