#17,367

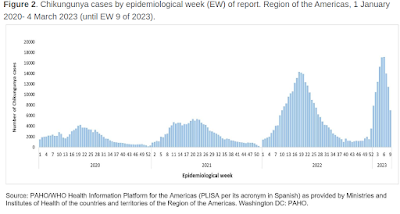

Twice over the past 6 weeks (see CDC HAN and PAHO report) we've looked at the rising number of Chikungunya and Dengue cases being reported in the southern half of the Americas, including their potential to spread to new geographic regions (including the United States).

While vector borne diseases don't tend to get the same level of respect as respiratory viruses, they can generate high morbidity and mortality in susceptible populations.

Yesterday the World Health Organization published a lengthy DON (Disease Outbreak News) report, and risk assessment, on the recent spike in arboviral disease transmission in the Americas. Due to its length, I've only posted some excerpts, so follow the link to read it in its entirety.

I'll have a bit more after you return.

Geographical expansion of cases of dengue and chikungunya beyond the historical areas of transmission in the Region of the Americas

23 March 2023

Situation at a glance

The increase in the incidence and geographical distribution of arboviral diseases, including chikungunya and dengue, is a major public health problem in the Region of the Americas (1). Dengue accounts for the largest number of cases in the Region, with epidemics occurring every three to five years. Although dengue and chikungunya are endemic in most countries of Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, in the current summer season, increased transmission and expansion of chikungunya cases have been observed beyond historical areas of transmission. Furthermore, 2023 is showing intense dengue transmission. In addition, higher transmission rates are expected in the coming months in the southern hemisphere, due to weather conditions favourable for the proliferation of mosquitoes.

There have been 2.8 million dengue cases reported in the Americas in 2022, which represents over a two-fold increase when compared to the 1.2 million cases reported in 2021. The same increasing trend has been observed for chikungunya, with a high incidence of meningoencephalitis possibly associated to chikungunya reported by Paraguay, which is of further concern.

At the regional level, WHO is assessing the risk as high due to the widespread presence of vector mosquitoes, the continued risk of severe disease and even death, and the expansion outside of historical areas of transmission, where all the population, including risk groups and healthcare workers, may not be aware of clinical manifestations of the disease, including severe clinical manifestations; and where populations may be immunologically naïve (2).

Regional overview

In 2022, a total of 3 123 752 cases (suspected and confirmed) of arboviral disease were reported in the Region of the Americas. Of these, 2 809 818 (90%) were dengue cases and 273 685 (9%) were chikungunya cases. This represents a proportional increase of approximately 119% compared to 2021. In 2022, both dengue and chikungunya peaked at epidemiological week (EW) 18 (week commencing 1 May 2022) (3).

WHO risk assessment

Dengue and chikungunya can have serious public health impacts. The viruses that cause these infections have been circulating in the Region of the Americas for decades due to the widespread spread of the Aedes spp. mosquitoes (mainly, Aedes aegypti). These arboviruses can be carried by infected travelers (imported cases) and may establish new areas of local transmission in the presence of vectors and a susceptible population. As they are arboviruses, all populations in areas where the mosquito vectors are present are at risk, however, the impact is greatest among the most vulnerable people, for which the arboviral disease programs do not have enough resources to respond to outbreaks.

Although dengue and chikungunya are endemic in most tropical and subtropical countries of the Americas and the Caribbean, increased transmission and expansion of chikungunya cases has been observed beyond historical areas of transmission. Furthermore, 2023 is showing intense dengue transmission.

The impact of the increased transmission in the Region will depend on several factors, including country capacities for a coordinated public health response and for clinical management; the early start of the arbovirus season in the southern cone; high mosquito densities due to interrupted vector control activities during the COVID-19 pandemic; and the large population susceptible to arbovirus infections, particularly in areas where these viruses are newly circulating. Competing disease priorities and risks may adversely affect disease control and proper clinical management, because of (i) misdiagnosis, given that chikungunya and dengue symptoms may be non-specific and resemble other infections, including Zika and measles, potentially leading to inadequate case management; (ii) overwhelmed healthcare facilities in some areas dealing with a high caseload and other concurrent outbreaks; and (iii) the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the decrease of resources available to arboviral disease programs and the need for capacity building and training of vector-control and healthcare workers, as well as maintenance and procurement of equipment and insecticides to perform vector control activities.

The apparent higher proportion of acute meningoencephalitis attributed to chikungunya in Paraguay is of concern. It is not yet known what is causing a higher rate of neurologic disease, which is considered an atypical clinical presentation. Sequencing has identified the East-Central-South-African (ECSA) lineage, which is expanding in geographic range within the region, having first been identified in Brazil in 2014. Introduction of chikungunya virus into new areas with immunologically naïve populations would promote further spread.

Aedes spp. mosquitoes are widely distributed in the Region of the Americas, therefore cross-border transmission of dengue and chikungunya is likely. Countries bordering areas with very high transmission of these diseases may be at higher risk, e.g., those adjacent to Bolivia (dengue) and Paraguay (chikungunya). Additionally, the Southern Hemisphere summer, with high temperatures and high levels of humidity, affects vector dynamics and may increase the likelihood of arboviruses transmission.

Thus, the risk at the regional level is assessed as high, due to the widespread presence of the mosquito vector species (especially Aedes aegypti), the continued risk of severe disease and even death, and the expansion outside of historical areas of transmission, where all the population, including risk groups and healthcare workers, may not be aware of warning signs and may be immunologically naïve. Moreover, one country in the Region (Paraguay) is experiencing an unprecedented increase of chikungunya cases, and another country in the Region (Bolivia) is experiencing high incidence of dengue cases.

Other challenges reported by Member States in the Region include stockouts of several essential supplies for prevention and control, lack of reagents and consumables for laboratory diagnosis, and the need for re-training of field teams and health workers. In addition, higher transmission rates are expected in the coming months, due to weather conditions favourable for vector breeding in the first semester of the year in the southern hemisphere.

Ninety years of aggressive mosquito control efforts - particularly in places like Florida, Puerto Rico, and Texas - have helped to keep mosquito borne diseases like Malaria, Yellow Fever, Dengue and Chikungunya at bay in the United States.

But it gets tougher every year.

Climate change, a steady influx of infected (viremic) travelers from endemic regions, and the arrival of new insect vectors (see UF/IFAS study: new mosquito species reported in Florida), all threaten to erode 80 years of progress in controlling these disease threats.

| |

| Outbreaks of yellow fever reported during 1693–1905 among cities comprising part of present-day United States. - Credit EID Journal |

The arrival in 1999 of a virus previously unseen in North American birds - West Nile Virus - began to spread from New York, and in a few short years it had established itself across much of the United States.

Today, WNV is reported in every state in the lower 48, and across much of Canada. According to a 2021 PLoS study (A 20-year historical review of West Nile virus), this virus has exacted a heavy toll on public health:

In the 20 years since West Nile virus (WNV) first emerged in the United States, more than 51,000 clinical cases have been reported, including more than 2,300 deaths, while an estimated 7 million people have been infected.