#17,289

Up until 18 about years ago, Chikungunya was a rarely seen mosquito-borne virus pretty much limited to central and eastern Africa. All of that changed in 2005 when it jumped to Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean, where it reportedly infected about 1/3rd of that island’s population (266,000 cases out of pop.770,000) in a matter of a few months.

From there, apparently aided and abetted by a new mutation that allowed it to be carried by the Aedes Albopictus `Asian tiger’ mosquito (see A Single Mutation in Chikungunya Virus Affects Vector Specificity and Epidemic Potential), it quickly cut a swath across the Indian ocean and into the Pacific.

Chikungunya typically produces a fever, severe muscle and joint pain, and headaches. The symptoms usually go away after a few weeks, but some patients can sustain permanent disability, and some deaths have been reported.

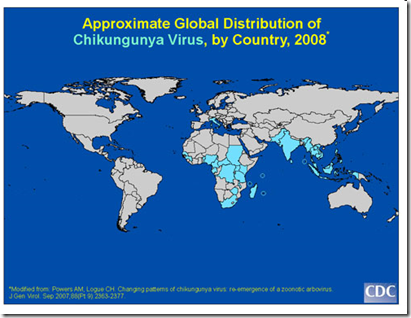

By 2008 Chikungunya was well entrenched in India, Indonesia, and Southeast Asia. But if you look carefully, you'll also see a blue spot in northern Italy, where an unexpected epidemic of the disease occurred in 2007. A traveler, returning from India, carried the virus to Italy in 2007 with more than 290 cases reported in the province of Ravenna, which is in northeast Italy (see It's A Smaller World After All). While the virus isn't normally found in Europe, its insect vector, the Aedes mosquito, is.

All it took was one infected person to arrive with the virus, and the chain of transmission began, ultimately infecting nearly 300 people.

In December of 2013, Chikungunya arrived in the Americas (St. Martin) for the first time (see CDC Update On Chikungunya In The Caribbean), presumably imported by international travelers who visited while viremic, and inadvertently introduced the virus to the local mosquito population.

From there it quickly spread across the Caribbean, Central and South America, and by the summer of 2014 even made inroads into Florida (see CDC Statement On 1st Locally Acquired Chikungunya In United States).That could change in the future, with climate change and increasing reports of insecticide resistant mosquitoes (see Science Advances: A Widespread Super–Insecticide-Resistant Aedes aegypti Mosquito in Asia) that threaten to degrade mosquito control efforts.Puerto Rico saw a significant Chikungunya epidemic in 2014-15 (see EID Journal High Incidence of Chikungunya Virus and Frequency of Viremic Blood Donations during Epidemic, Puerto Rico, USA, 2014), but the virus has never really established itself in the lower 48 states.

But 2022 showed a decided increase in CHKV cases, and the first 4 weeks of 2023 has continued that trend (see chart below), leading PAHO to issue an Epidemiological alert for the Americas for the coming year.

Epidemiological Alert

Chikungunya increase in the Region of the Americas

13 February 2023

In 2022, the number of cases and deaths due to chikungunya in the Region of the Americas were above the numbers reported in previous years. The first weeks of 2023 have seen this trend continuing with the increase in cases and deaths becoming more evident. Due to this increasing trend, the Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) recommends Member States intensify actions to prepare health care services, including the diagnosis and proper management of cases, to face possible outbreaks of chikungunya and other arboviral diseases, to minimize deaths and complications from these diseases.

Situation summary

Between epidemiological week (EW) 1 and EW 52 of 2022, a total of 271,176 cases of chikungunya 1 , including 95 deaths 2,3 , were reported in 13 of the countries and territories of the Region of the Americas. This figure is higher than that observed in the same period of 2021 (137,025 cases, including 12 deaths). During the first four epidemiological weeks of 2023, 30,707 cases and 14 deaths 3 due to chikungunya were reported (Figure 1 and 2).

The increase in cases and deaths from chikungunya compared to the numbers reported in recent years are in addition to the simultaneous circulation of other arboviral diseases, such as dengue and Zika, both transmitted by the same vectors, Aedes aegypti (most prevalent) and Aedes albopictus, which are present in almost all countries and territories of the Region of the Americas.

Additionally, several countries in the Region, especially in the Southern Cone, will have an increase in temperature related to the summer season during the first half of 2023, which, depending on its magnitude and impact on the endemic areas of arboviruses, could constitute an additional burden of these diseases for health systems in the affected areas.

It is very important for the entire southern hemisphere to be extremely vigilant and prepared to intensify prevention and control actions in the face of any increase in cases of arbovirus in this first half of 2023 and especially chikungunya, given the number of susceptible people since it has been eight years since the 2014 epidemic, the last major outbreak of chikungunya in the Americas.

While the threat from CHKV, Dengue, and even Zika may seem minor compared to our COVID pandemic, and the potential for something worse from avian flu, vector-borne diseases can have a serious impact, even in the United States and Europe.

As we've discussed previously (see EID Journal: Hx of Mosquitoborne Diseases In the U.S. & Implications For The Future), the United States is not immune to imported exotic mosquito-borne diseases.

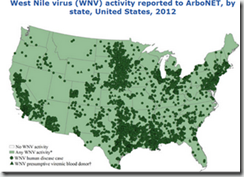

West Nile Virus, which infects tens of thousands of people each year (killing hundreds), only first arrived in 1999, but quickly became endemic and spread across the nation.

Not that long ago Malaria, Dengue and Yellow Fever were fairly widespread and caused major epidemics in the United States (see map below).

| |

| Outbreaks of yellow fever reported during 1693–1905 among cities comprising part of present-day United States. - Credit EID Journal |

Large swaths of the United States have mosquito species that would be competent vectors for Yellow Fever, Zika, Chikungunya, Japanese encephalitis, Rift Valley Fever, and Dengue.

And with predicted climate changes, those areas are likely to increase over time.

For more on insect vector disease threats, you may wish to revisit:

Nosocomial Outbreak of SFTS Among Healthcare Workers in a Single Hospital in Daegu, Korea

UK: UKHSA Reports Imported Case Of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

CDC COCA Call: Lyme Disease Updates and New Educational Tools for Clinicians