#17,431

While historically influenza viruses - and more recently coronaviruses - have dominated discussions of potential pandemic pathogens, there is ample evidence throughout history that other diseases can be contenders.

The Black Death (bubonic plague), Cholera, HIV, and even mosquito borne illnesses like Malaria, Yellow Fever, and Dengue have all produced pandemics or widespread epidemics causing severe morbidity and mortality.

And there are numerous reports of mysterious, still unidentified diseases in the past, including:

- febris comatosa which sparked a severe epidemic in London between 1673 and 1675

- in the wake of the 1889–1890 influenza pandemic, a severe wave of somnolent illnesses (nicknamed the "Nona") appeared.

- and Encephalitis Lethargica which killed millions in the 10 years following the Great Influenza pandemic of 1918

While we may not know the etiology of these disease outbreaks, it is probably safe to say most were zoonotic in origin, and that there are probably a lot more out there in the wild like them that we have yet to identify.

A decade ago, in mBio: A Strategy To Estimate The Number Of Undiscovered Viruses, we saw an estimate that there were at least 320,000 unidentified mammalian viruses awaiting discovery. Most are benign or of little consequence, but among them are probably scores of high consequence pathogens.

In 2018 the World Health Organization released their second update of their WHO List Of Blueprint Priority Diseases, which listed 8 priority diseases and pathogens to prioritize for research and development.

- Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

- Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

- Nipah and henipaviral diseases

- Rift Valley fever (RVF)

- Zika

- Disease X

Disease X being the catch-all name for the pathogens out there with pandemic potential that we have yet to identify. Most of them - like SARS-CoV-2 - are destined to fly below the radar until they evolve (as did COVID) into a public health threat.

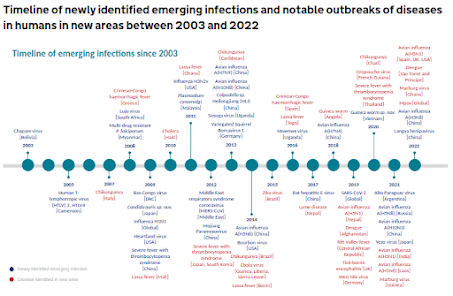

Every few months we learn about new or expanding threats in the wild (see UK HAIRS Timeline below), and there are no signs this trend is slowing down.

All of which brings us to a lengthy, detailed, and at times technical review of zoonotic viruses detected across more than 2,000 animals collected in South China between 2015 and 2022.

Due to its length, I've only posted the link, abstract, and some brief excerpts. Those interested in taking a deep dive will want to follow the link to read it in its entirety.

Virus diversity, wildlife-domestic animal circulation and potential zoonotic viruses of small mammals, pangolins and zoo animalsXinyuan Cui, Kewei Fan, Xianghui Liang, Wenjie Gong, Wu Chen, Biao He, Xiaoyuan Chen, Hai Wang, Xiao Wang, Ping Zhang, Xingbang Lu, Rujian Chen, Kaixiong Lin, Jiameng Liu, Junqiong Zhai, Ding Xiang Liu, Fen Shan, Yuqi Li, Rui Ai Chen, Huifang Meng, Xiaobing Li, Shijiang Mi, Jianfeng Jiang, Niu Zhou,… Yongyi Shen Show authors

Nature Communications volume 14, Article number: 2488 (2023) Cite this article

Abstract

Wildlife is reservoir of emerging viruses. Here we identified 27 families of mammalian viruses from 1981 wild animals and 194 zoo animals collected from south China between 2015 and 2022, isolated and characterized the pathogenicity of eight viruses. Bats harbor high diversity of coronaviruses, picornaviruses and astroviruses, and a potentially novel genus of Bornaviridae.In addition to the reported SARSr-CoV-2 and HKU4-CoV-like viruses, picornavirus and respiroviruses also likely circulate between bats and pangolins. Pikas harbor a new clade of Embecovirus and a new genus of arenaviruses. Further, the potential cross-species transmission of RNA viruses (paramyxovirus and astrovirus) and DNA viruses (pseudorabies virus, porcine circovirus 2, porcine circovirus 3 and parvovirus) between wildlife and domestic animals was identified, complicating wildlife protection and the prevention and control of these diseases in domestic animals.This study provides a nuanced view of the frequency of host-jumping events, as well as assessments of zoonotic risk.

(SNIP)

Herein, we used meta-transcriptomic sequencing to determine the viromes in small mammals (bats, rodents, insectivores, and pikas), pangolins and zoo animals collected in South and Southwest China (Supplementary Data 1), and from this determine the extent and pattern of cross-species virus transmission. We also isolated some of the viruses identified and performed experimental infection studies. This work documents virus diversity and identifies viruses in wildlife with zoonotic potential.

(SNIP)

Overview of animal viromes

A total of 503 libraries representing 2175 individual animals that were collected between 2015 and 2022 were sequenced (Supplementary Data 1). In brief, there were 214, 123, 18, 21, 56, and 71 libraries from bats, rodents, pikas, insectivores, pangolins and zoo animals, respectively. An average of 12 Gb of sequence data was obtained for each library. We focus only on the viruses that are able to infect vertebrates, while those infecting archaea, bacteria, fungi, invertebrates, and plants were excluded. An overview of the reads for the mammalian viruses is presented in Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Data 2. A total of 328 viruses were identified through phylogenetic analyses, with 171 of them having near-complete genomes, and 167 of them were unreported (Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Table 1).

Rodents had 20 virus families, followed by bats, insectivores and zoo animals (with 19, 15, and 14 virus families, respectively), whereas pikas and pangolins showed the presence of the fewest number of viral families (nine each). Viral reads from the families Arenaviridae, Arteriviridae, Astroviridae, Caliciviridae, Circoviridae, Coronaviridae, Flaviviridae, Hantaviridae, Hepeviridae, Herpesviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Parvoviridae, Picornaviridae, and Reoviridae were widely distributed in these animals. These viruses were further confirmed by RT-PCR (RNA viruses) and PCR (DNA viruses), with the details shown in Supplementary Data 4. The reads of Retroviridae and Herpesviridae derived from the host genomes could not be excluded since the genomes of most of the tested animals are not available. Therefore, the abundance of Retroviridae and Herpesviridae in the heatmap might be overestimated.

(SNIP)

Conclusion

(excerpt)

The continual outbreaks caused by emerging and reemerging viruses raises considerable concern over the roles of wildlife, especially in those species that frequently contact humans and domestic animals. This study has revealed the diversity of mammalian viruses in some important mammals, and identified a series of novel genera and species of viruses with some of them having potential for cross-species transmission. More surveillance of wildlife-borne viruses, particularly at the wildlife-domestic animal-human interface, is needed to prevent outbreaks of emerging and reemerging viral diseases.

Suffice to say, when it comes to identifying zoonotic disease threats, we are barely scratching the surface of what is out there.

Eighteen months ago, in PNAS Research: Intensity and Frequency of Extreme Novel Epidemics, researchers suggested that the probability of novel disease outbreaks will likely grow three-fold in the next few decades.

Looking at the plethora of pathogens in the wild, its hard not to consider that an optimistic assessment.