#17,430

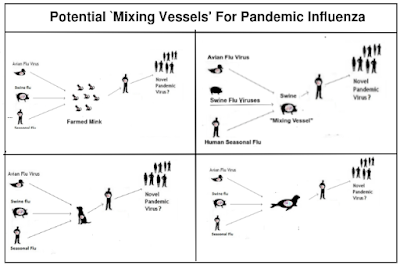

Since zoonotic influenza viruses - like H5N1, H3N8, or H9N2 - circulate in non-human hosts, we focus on ways these viruses could evolve into human adapted viruses. Usually that involves a series of reassortment events (`antigenic shift') - the combining of two or more flu viruses in a single host - aided and abetted by `antigenic drift'.

NIAID, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has a pair of short (3 minute) videos on YouTube ( How Influenza Pandemics Occur and Influenza: Antigenic Drift) that illustrate both in action.

Swine served as reassortment hosts for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus, but the origins of the 1968 (H3N2) and 1957 (H2N2) pandemic viruses are still murky. Both involved a reassortment of a novel flu virus (avian H2 in 1957 and avian H3 in 1968) with the current human seasonal flu virus (H1N1 in 1957, H2N2 in 1968), producing a novel virus.

Even though both of these pandemics occurred in the `modern era' of virology, we don't know with certainty in what host these reassortments occurred. But since it involved the then circulating seasonal flu, and an avian strain, a human host seems likely.

One of the things we've learned in the past couple of decades about influenza is that humans - much like birds and pigs - can be co-infected with 2 or more flu viruses simultaneously. Up until 2009, human co-infection with influenza A had only rarely been reported.

In 2008, we saw a report of an Indonesian teenager who tested positive both H5N1 and the seasonal flu strain H3N2 (see CIDRAP report Avian, human flu coinfection reported in Indonesian teen), demonstrating that co-infection with Influenza A was possible.Dual infections had been noted, but usually with an `A’ and a `B’ virus.

But the big breakthrough came in 2009 when the pandemic H1N1 virus emerged and co-circulated for a time with the old seasonal H1N1 virus, allowing scientists in New Zealand to isolate and document 11 cases of Influenza A co-infection (see EID Journal: Co-Infection By Influenza Strains for the full story).

(2019) Eurosurveillance: Novel influenza A(H1N2) Seasonal Reassortant - Sweden, January 2019

(2019) Denmark Reports Novel H1N2 Flu Infection

(2016) J Clin Virol: Influenza Co-Infection Leading To A Reassortant Virus

(2014) EID Journal: Human Co-Infection with Avian and Seasonal Influenza Viruses, China

(2013) Lancet: Coinfection With H7N9 & H3N2

(2011) Webinar: pH1N1 – H3N2 A Novel Influenza Reassortment

Luckily, most reassortant viruses aren't biologically `fit' enough to compete with more established strains, and quickly fade away, often without ever being noticed. If creating a pandemic virus were easy, we'd be hip deep in them all the time.

But with record levels of avian H5N1 being reported globally, the opportunities for it to meet up with a better adapted seasonal virus in a human host are increasing. And that raises the likelihood that an H5N1/H1N1 or H5N1/H3N2 reassortant could emerge.

After three years of the COVID pandemic, and round-after-round of COVID shots, many people are weary of getting vaccines, including for seasonal flu. While understandable, not vaccinating against seasonal flu provides additional opportunities for H5N1 (or H5N6, H3N8, H9N2, etc.) to reassort in a human host.

Granted, there are other pathways that these viruses could take to become a pandemic. But the most straightforward way is by reassorting with an already `humanized' flu virus.

It is for this reason (and concerns over reverse zoonosis) that the CDC, and other health agencies around the world, recommend that poultry and swine workers get vaccinated against seasonal flu every year (see The Importance of Including Swine and Poultry Workers in Influenza Vaccination Programs).

Up until fairly recently, H5N1 exposure was pretty much limited to poultry workers, but with the virus rapidly becoming endemic in wild birds (and increasingly spilling over into mammals) around the world, the risks of exposure - while still low - are increasing for other cohorts.

While there are plenty of other good reasons to get the flu shot every year (see here, here, and here), if you are still on the fence and need more motivation, then maybe lowering the opportunities for H5N1 to reassort in a human host will suffice.

Granted, it is a bit of a long-shot. But it beats doing nothing.