#17,425

While we are understandably concerned about the emergence of new, or exotic, pathogens - like MERS-CoV, Avian H5 viruses, Swine-Variant flu viruses, or even `Virus X' (the one we don't know about, yet) - seasonal influenza also has the ability to reinvent itself into a more formidable foe.And on rare occasions, the resultant strain can even approach the ferocity of a novel pandemic virus.

Across large swaths of the globe, however, there is little surveillance or reporting on seasonal flu viruses. Even in North America, Europe, Australia, and Japan - all of which maintain modern surveillance systems - only a small percentage of viral infections are tested and sequenced.

About a month ago, in UK Novel Flu Surveillance: Quantifying TTD, we looked at an analysis by the UKHSA of their ability to detect community spread of a novel H5N1 virus. In a country with arguably one of the better surveillance systems in the world, they found:

It would likely take between 3 and 10 weeks before community spread of H5N1 would become apparent to authorities, after anywhere between a few dozen to a few thousand community infections.

During a swine variant flu outbreak here in the United States a dozen years ago, a study published in 2013 (see CID Journal: Estimates Of Human Infection From H3N2v (Jul 2011-Apr 2012) - estimated that during a time when only 13 cases were reported by the CDC - that the actual number of infections was likely 200 times (or more) higher.

In places like Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and much of Asia, detection would likely take far longer.

We often hear of outlier `flu epidemics', where some country or region is hit unusually hard by seasonal H1N1 or H3N2, but only rarely do we see a proper analysis of the reasons behind it.

Sometimes, all it takes is a single mutation to make a `mild' flu virus more deadly, as in the case of D225G, which can increase H1N1's ability to ability to bind deep into the lungs.

Other South American countries, including Bolivia and Argentina, reported similar outbreaks around the same time. But until now, the reasons behind Brazil's outlier epidemic have been unknown.

Today we have a report published in the journal Viral Evolution - that looks at 7 year's worth of flu sequences from Brazil, and identifies a new clade of H1N1 (6b1) as having sparked the severe outbreak 7 years ago.

First the abstract, and a few excerpts, after which I'll return with a postscript.

(SNIP)Tracking the emergence of antigenic variants in influenza A virus epidemics in Brazil

Tara K Pillai, Katherine E Johnson, Timothy Song, Tatiana Gregianini, Tatiana G Baccin, Guojun Wang, Rafael A Medina, Harm Van Bakel, Adolfo García-Sastre, Martha I Nelson

Virus Evolution, vead027, https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vead027

Published: 25 April 2023 Article history

AbstractInfluenza A virus circulation patterns differ in North America and South America, with influenza seasons often characterized by different subtypes and strains. However, South America is relatively under sampled considering the size of its population. To address this gap, we sequenced the complete genomes of 220 influenza A viruses collected between 2009 and 2016 from hospitalized patients in southern Brazil.

New genetic drift variants were introduced into southern Brazil each season from a global gene pool, including four H3N2 clades (3C, 3C2, 3C3, and 3C2a) and five H1N1pdm clades (clades 6, 7, 6b, 6c, and 6b1).

In 2016, H1N1pdm viruses belonging to a new 6b1 clade caused a severe influenza epidemic in southern Brazil that arrived early and spread rapidly, peaking mid-autumn. Inhibition assays showed that the A/California/07/2009(H1N1) vaccine strain did not protect well against 6b1 viruses. Phylogenetically, most 6b1 sequences that circulated in southern Brazil belong to a single transmission cluster that rapidly diffused across susceptible populations, leading to the highest levels of influenza hospitalization and mortality seen since the 2009 pandemic.

Continuous genomic surveillance is needed to monitor rapidly evolving influenza A viruses for vaccine strain selection and understand their epidemiological impact in understudied regions.

The severe H1N1pdm epidemic in 2016 in RS was unexpected. For one, the H3N2 subtype is more often the cause of severe influenza seasonal epidemics (Thompson, Shay et al. 2003), and H3N2 was the dominant subtype circulating in RS in 2015.Little antigenic evolution had been observed in the H1N1pdm virus since the 2009 pandemic, requiring no updates to the H1N1pdm vaccine strain for six years. Presumably, after 5–6 years of H1N1pdm circulation, population immunity had built against H1N1pdm on a global scale, increasing selection pressure for new antigenic variants.The severe H1N1pdm epidemic in Brazil was also unexpected given that the United States did not have a severe influenza season in 2015–2016 (the US did have a severe flu season in 2016–2017, but it was dominated by H3N2 viruses). The number of cases and genetic composition of the winter influenza season in North America is not always predictive of what is seen in the Southern hemisphere six months later. Likewise, the subtype that circulates during winter in the Southern hemisphere is not necessarily the same that circulates later on in the Northern hemisphere.It remains unclear whether new mutations that occurred in the 6b1 South American viruses had any phenotypic effect. Our antigenic assays confirmed that people infected with 6b1 viruses in RS were poorly protected by the A/California/07/2009(H1N1) vaccine strain, but we did not compare the immunological response to the Brazilian strains against the US strains circulating the prior winter.

For reasons that are not well understood, this severe H1N1 epidemic did not spread outside of South America. Instead a mutated H3N2 virus dominated both Europe and North America over the 2016-2017 flu season (see The Enigmatic, Problematic H3N2 Influenza Virus).

Seasonal flu vaccines briefly shifted to an H1N1 A/Michigan/45/2015 subclade 6B.1 component, and that may have helped in subsequent years.

If all of this sound vaguely familiar, in 2018's Remembering 1951: The Year Seasonal Flu Went Rogue, we looked at another unusually deadly regional wave of influenza during an otherwise mild non-pandemic year.

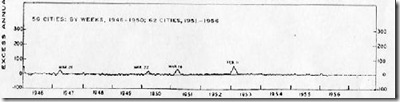

The winter of 1950-1951 had been an average flu year, with the dominant flu called the `Scandinavian strain', producing mild illness in most of its victims. In fact, if you look at a graph of flu activity for the United States, running from 1945 to 1956, you'll see nary a blip.

But in December of 1950 a new strain of virulent influenza appeared in Liverpool, England, and by late spring, it had spread across much of England, Wales, and parts of Canada.

The following comes from an absolutely fascinating EID Journal article: Viboud C, Tam T, Fleming D, Miller MA, Simonsen L.

1951 influenza epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States.

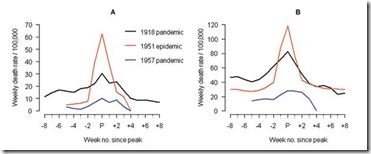

The 1951 influenza epidemic (A/H1N1) caused an unusually high death toll in England; in particular, weekly deaths in Liverpool even surpassed those of the 1918 pandemic. . . . . Why this epidemic was so severe in some areas but not others remains unknown and highlights major gaps in our understanding of interpandemic influenza.

According to this study, the effects on the city of origin, Liverpool, were horrendous.

In Liverpool, where the epidemic was said to originate, it was "the cause of the highest weekly death toll, apart from aerial bombardment, in the city's vital statistics records, since the great cholera epidemic of 1849" (5). This weekly death toll even surpassed that of the 1918 influenza pandemic (Figure 1)

For roughly 5 weeks Liverpool saw an incredible spike in deaths due to this new influenza. And it didn’t just affect Liverpool. While it appears not to have spread as easily as the dominant Scandinavian strain, it managed to infect large areas of England, Wales, and Canada over the ensuing months.

Getting started relatively late in the flu season, this new strain never managed to spread much beyond UK and Eastern Canada. Nor did it reappear the following flu season. It simply vanished as mysteriously as it appeared.

While we don't know what made either of these two regional outbreaks so deadly, we do know that seasonal flu can abruptly shift gears, which is why we desperately need better surveillance around the world.