#17,452

While we've seemed on the precipice with H5 avian flu several times before, this week the ECDC's Eurosurveillance Journal has published an editorial by Cornelia Adlhoch and Francesca Baldinelli called Avian Influenza, New Aspects of an Old Threat which discusses new and concerning changes in the virus's behavior in the wild.This is an excellent review of the major epidemiological changes we've seen with H5N1 over the past couple of years, and well worth reading in its entirety.

Due to its length, I've only reproduced the opening and closing paragraphs. I'll have a bit more about our 2-decade long journey with H5N1 after the break.

Avian influenza, new aspects of an old threat

Cornelia Adlhoch1, Francesca Baldinelli2

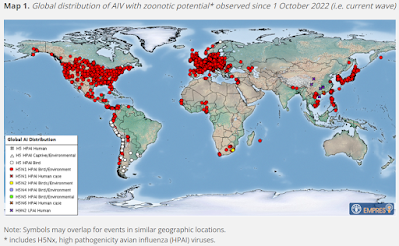

Since early 2020, while the worldwide focus was on the COVID-19 pandemic, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5) viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b caused the worst ever observed epidemics in birds during the 2020/21, 2021/22 and ongoing 2022/23 epidemic years in Europe. They caused 14,325 reported outbreaks with devastating consequences for farmed poultry, resulting in the culling of roughly 96 million farmed birds in Europe. Some remarkable changes of epidemiology have been observed over the last years in relation to circulating HPAI viruses of the H5 subtype.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza epidemics in Europe used to be a seasonal phenomenon associated with migratory waterfowl returning to the overwintering sites in Europe in autumn, causing spill-over to farmed birds and outbreaks in poultry in the autumn/winter with some limited circulation in the spring. In 2021, for the first time, a few HPAI virus findings in wild birds continued over the summer in some breeding areas in northern Europe [1]. They were followed in 2022 by large outbreaks in the winter and spring in wild birds, that continued during the summer months with mass mortality in colony-breeding seabirds in several European countries.

In addition to the change in seasonality there was notable large global expansion and in 2020, A(H5) HPAI viruses of clade 2.3.4.4b spread west to east along migratory bird routes and were detected in south-east Asia [2]. In 2020/21 and 2021/22, a Europe-wide extension of the affected geographical areas was observed, including in countries that had never detected HPAI viruses before, such as Iceland, Norway (including Svalbard), and Greenland. An east to west spread via Iceland and Greenland was observed for the first time with A(H5N1) virus introductions from Europe to North America, progressing rapidly across large areas of Canada and the United States (US). Similar to the European situation, massive outbreaks in wild birds and spill-over to poultry farms causing extensive losses were observed. A north to south spread from Europe and North America to Africa and Central and South America, respectively, occurred as well [3]. The rapid expansion of A(H5N1) viruses following their introduction during the autumn bird migration in Central and South America down to the southern tip of Chile is unprecedented.

To tackle the threat of avian influenza, a One Health approach is needed through rapid sharing of information about outbreaks, provision of sequence data and reference viruses, and close collaboration between the different sectors locally and globally. Communication campaigns may help to increase awareness in the population and recognise avian influenza viruses as a threat to animal and human health, in order to reduce the risk of contact with potentially infected animals.

With the ongoing global presence of A(H5) HPAI viruses, further sporadic spill-over events to humans cannot be excluded. It is crucial to identify such events as early as possible to timely initiate appropriate measures across all sectors.

The HPAI H5N1 virus has been with us since the mid-1990s, but the virus of today is a very distant relative of that original virus.

HPAI viruses - which were common in poultry (aka `fowl plague') - had never been detected in wild or migratory birds prior to 1996. That year a previously unknown H5N1 virus (clade 0) was detected in a domestic goose in Guangdong Province, China (A/Goose/Guangdong/1/1996 (GsGD)).

The following year H5N1 appeared in Hong Kong's chickens, and sparked the first human epidemic, hospitalizing 18 and killing six (see Outbreak of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in Hong Kong in 1997).

The bold decision to cull every chicken in Hong Kong, and the immediate isolation of cases, were credited with stopping that first outbreak.

The H5 virus appeared to go to ground for the next five years, but re-emerged again in early 2003 - albeit as a new clade - in Hong Kong when two members of a family fell ill (one fatally) after returning from Fujian Province on the Mainland. A third relative died (untested) on the mainland. |

| Credit WHO |

Within a year, new variants of H5N1 virus caused outbreaks in poultry, wild birds, hundreds of humans, and dozens of captive animals from Beijing and Korea to Thailand and Vietnam.

Two years later - after a new clade emerged at Qinghai Lake (China) - H5N1 spread out of Asia and moved into Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

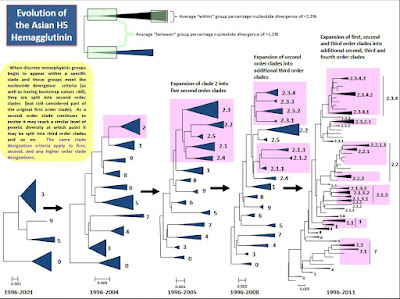

And as H5N1 expanded geographically, it expanded genetically as well (see chart below), forming numerous new subtypes (e.g. H5N6,H5N8, H5N5, etc.), new clades, subclades, and genotypes.

Many of these variants were less `fit' than their competition, and died out along the way, but others thrived and survived, and became the dominant clade in different parts of the world.

Over the years we've seen several sudden expansions of the H5 virus (2005, 2009, 2015-16, and most recently 2020-21). Each one occurred after a major evolutionary change to the virus (new clade or new reassortment).

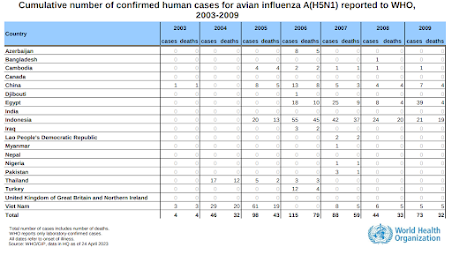

While today's H5N1 virus is thankfully not spilling over into humans at the rate same we were seeing in the mid 2000s (see chart below), it is far better suited for long distance carriage by migratory and wild birds, has spread globally at a phenomenal rate, and continues to experiment with new mammalian hosts.

While the future course and impact of HPAI H5N1 is unknowable - and the threat may recede as it has in the past - these recent developments are red flags we can't afford to ignore.