#17,457

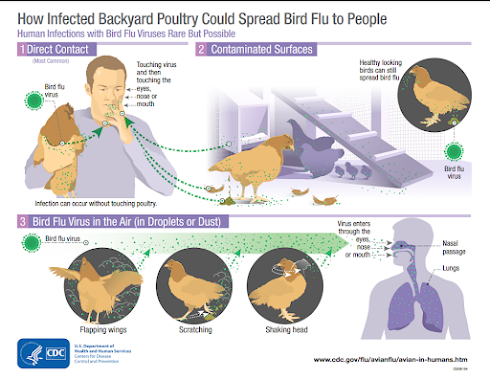

One of the things we've learned about avian flu over the past couple of decades is that the virus can be spread via the `dust' (dried feces, feathers, other contaminants, etc.) that abound in wet markets and poultry farms.

Eight years ago, in CIDRAP: H5N2 Roundup & Detection In Environmental Air Samples, we looked at air sampling conducted by the University of Minnesota around infected poultry farms that found evidence of airborne virus particles.

More recently, in 2022's Zoonoses & Public Health: Aerosol Exposure of Live Bird Market Workers to Viable Influenza A/H5N1 and A/H9N2 Viruses, Cambodia, we looked at a study that documented high levels of viable H5 & H9 viruses in the air at a Cambodian LBM during the `high season' for avian flu.

Which means that it would not be unexpected to see H5N1 positive nasal and throat swabs from poultry workers, even if they aren't truly infected.

Today the UK HSA is reporting on two asymptomatic poultry workers whose nasal and throat swabs have tested positive for H5N1. At this time, the jury is still out on whether either of them was actually infected, but hopefully follow-up serology tests will provide better answers.

The UK's press release follows, after which I'll have a bit more on the difficulties in detecting cases, particularly in the general public.

Avian flu detected in 2 individuals taking part in testing programme

UKHSA has detected influenza A (H5) virus in 2 poultry workers, following the introduction of an asymptomatic testing programme for people who have been in contact with infected birds.

Published16 May 2023

Last updated16 May 2023 — See all updates

The 2 people returning positive tests are known to have recently worked on an infected poultry farm in England. Neither has experienced any symptoms of avian influenza and both have since tested negative.

Detection of avian influenza in poultry workers can follow contamination of the nose and throat from breathing in material on the affected farm or can be true infection. It can be difficult to distinguish these in people who have no symptoms.

Based on the timing of exposures and test results, one individual is likely to have had contamination of the nose and/or throat from material inhaled on the farm, while for the second individual it is more difficult to determine which is the case. Further investigation is under way but meanwhile precautionary contact tracing has been undertaken for this second individual.

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has not detected evidence of human-to-human transmission and these detections do not change the level of risk to human health, which remains very low to the general population.

Professor Susan Hopkins, Chief Medical Advisor at UKHSA, said:

Current evidence suggests that the avian influenza viruses we’re seeing circulating in birds around the world do not spread easily to people. However, we know already that the virus can spread to people following close contact with infected birds and this is why, through screening programmes like this one, we are monitoring people who have been exposed to learn more about this risk.Globally there is no evidence of spread of this strain from person to person, but we know that viruses evolve all the time and we remain vigilant for any evidence of changing risk to the population.It remains critical that people avoid touching sick or dead birds, and that they follow the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) advice about reporting.

UKHSA has contact traced close contacts where needed. For those with the highest risk exposures, UKHSA health protection teams contact them daily to monitor for the development of any symptoms so that we can take appropriate action if necessary.

In the asymptomatic surveillance programme, poultry workers are asked to take swabs of their nose and throat which are tested for the presence of influenza virus, during the 10 days after their exposure. In some cases they may also be asked to have finger prick blood tests to see if UKHSA can detect antibodies against avian influenza, suggestive of an immune response in the blood.

As part of public health response, UKHSA follows up all individuals who have been in contact with a confirmed human case of avian influenza. For those with the highest risk exposures, we may offer testing and antivirals, to help protect them from infection as well as to reduce the risk of passing infection to others.

Guidance from Defra on the signs of bird flu and how to report it in poultry and other birds is available on GOV.UK, while further guidance on avoiding the risk of infection when working with infected poultry is published by the Health Safety Executive.

Six weeks ago, in UK Novel Flu Surveillance: Quantifying TTD, we looked at estimates of how many community H5N1 cases would probably be needed before the UK's surveillance system would sound an alarm on community spread.

By their own admission (see UKHSA Technical Briefing #3 & chart below), the Expected time to detection (TTD) and the cumulative number of infections (CI) before we'd know there was community spread are sobering.

The UK estimates it would likely take between 3 and 10 weeks before community spread would become apparent to authorities, after anywhere between a few dozen to a few thousand community infections.

And this is for the UK. Presumably the TTD in many less-developed regions would take longer.

As we've discussed previously, it requires more than a little luck to detect sporadic cases - such as we've seen in Peru and Chile - even in countries with well-equipped and functioning public health systems.