#17,646

As recently as a decade ago, there was still a bitter debate over whether migratory birds were A) capable of spreading HPAI viruses over long distances and B) whether migratory birds could bring Eurasian avian flu viruses to North America by crossing the Bering straits.

While it was known that some waterfowl species could carry HPAI viruses asymptomatically, the rallying cry that `Sick birds don’t fly’ was often used to argue that migratory birds couldn't be blamed for the international spread of the virus.

In January of 2014, in response to the South Korean assertion that migratory Birds were the likely source of their H5N8 outbreak, the UN's Scientific Task Force on Avian Influenza and Wild Birds quickly issued a statement saying:

"There is currently no evidence that wild birds are the source of this virus and they should be considered victims not vectors.

A year later - following the first transpacific spread of HPAI H5 to North America - they would modify their stance somewhat, stating that typically the `. . . spread of HPAI virus is via contaminated poultry, poultry products and inanimate objects although wild birds may also play a role'.

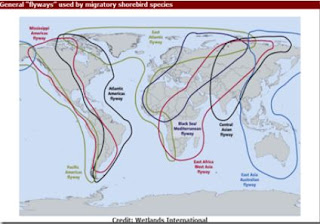

Despite the 2014 incursion of avian flu from Asia to Alaska (crossing the relatively narrow Bering Straits), the spread from Europe across a much wider Atlantic Ocean was still considered unlikely.

Still, a number of researchers thought it was possible (see 2014's PLoS One: North Atlantic Flyways Provide Opportunities For Spread Of Avian Influenza Viruses) with Iceland or Greenland cited as possible staging areas for bird flu.

In 2017, in Iceland Warns On Bird Flu, we saw reports suggesting that European birds carrying avian flu may have reached Iceland. Iceland is the first major landing spot for wing-weary travelers, followed by Greenland (see 2016's Avian Flu Surveillance In Greenland).

In late 2021, the inevitable happened, as HPAI H5 arrived in Eastern Canada and Western Canada via two different routes; crossing the Pacific and the Atlantic (Multiple Introductions of H5 HPAI Viruses into Canada Via both East Asia-Australasia/Pacific & Atlantic Flyways).

Changes in the HPAI H5 clade 2.3.4.4b virus since 2016 have undoubtedly increased its host range (both avian and non-avian), and its ability to be spread by migratory birds.

But today we have a report in the Journal Viruses presenting evidence that the Trans-Atlantic incursion of HPAI H5 in late 2021 was not an isolated incident, and that further exchange of viruses across oceans can be expected.

Due to its length, I've only some excerpts. Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a bit more after the break.

byTamiru N. Alkie 1,†, Alexander M. P. Byrne 2,†, Megan E. B. Jones 3,4, Benjamin C. Mollett 2, Laura Bourque 3, Oliver Lung 1, Joe James 2,5, Carmencita Yason 4, Ashley C. Banyard 2,5, Daniel Sullivan 1, Anthony V. Signore 1, Andrew S. Lang 6, Meghan Baker 7, Beverly Dawe 7,Ian H. Brown 2,5,* and Yohannes Berhane 1,8,9,*

Viruses 2023, 15(9), 1836; https://doi.org/10.3390/v15091836 (registering DOI)Received: 30 July 2023 / Revised: 21 August 2023 / Accepted: 23 August 2023 / Published: 30 August 2023

AbstractIn December 2022 and January 2023, we isolated clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 high-pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) viruses from six American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) from Prince Edward Island and a red fox (Vulpes vulpes) from Newfoundland, Canada. Using full-genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, these viruses were found to fall into two distinct phylogenetic clusters: one group containing H5N1 viruses that had been circulating in North and South America since late 2021, and the other one containing European H5N1 viruses reported in late 2022.

The transatlantic re-introduction for the second time by pelagic/Icelandic bird migration via the same route used during the 2021 incursion of Eurasian origin H5N1 viruses into North America demonstrates that migratory birds continue to be the driving force for transcontinental dissemination of the virus.

This new detection further demonstrates the continual long-term threat of H5N1 viruses for poultry and mammals and the subsequent impact on various wild bird populations wherever these viruses emerge. The continual emergence of clade 2.3.4.4b H5Nx viruses requires vigilant surveillance in wild birds, particularly in areas of the Americas, which lie within the migratory corridors for long-distance migratory birds originating from Europe and Asia.

Although H5Nx viruses have been detected at higher rates in North America since 2021, a bidirectional flow of H5Nx genes of American origin viruses to Europe has never been reported. In the future, coordinated and systematic surveillance programs for HPAI viruses need to be launched between European and North American agencies.

(SNIP)

Here, we demonstrated a new incursion of a genetically distinct H5N1 HPAI virus into Eastern Canada during late 2022, representing a second incursion into this region after clade 2.3.4.4b HPAIV first arrived in North America in late 2021. On both occasions, the most parsimonious explanation is that the virus had been translocated by migratory birds from Northern Europe via the transatlantic route.

The continual emergence of clade 2.3.4.4b viruses in avian hosts [35] requires vigilant surveillance for avian influenza in wild birds, particularly in areas of the Americas that are entry points for long-distance migratory birds from Europe and Asia. This complex and intertwining inter-continental seasonal connectivity of wild birds has led to the introduction of H5Nx HPAI viruses to Canada four times so far during 2014/2015, late 2021, winter/spring 2022 and winter 2022/2023, and raises the possibility that this could become a regular occurrence if these viruses remain circulating in wilds birds.

To date, this flow of viruses has only been detected from Europe to North America, but the continued circulation of these viruses in wild birds and their increasing expansion in host ranges (including new bird taxa) creates increased opportunity for the spread of the virus through multiple wild bird migratory pathways, both short and long.

The possibility of bi-directional translocation of viruses is highly plausible given the known wild bird movement pathways (albeit smaller in scale than north to south routes) and considering the genetic diversity, increasing the likelihood that viruses which have evolved independently in the Americas could be detected on the eastern Atlantic seaboard. This level of risk reinforces the need for enhanced genetic surveillance, which is crucial to identifying such occurrences.

All of this matters because influenza's superpower is its ability to reassort; to reinvent itself by `borrowing' genetic material from other flu viruses it encounters in its journeys. The more diverse the array of viruses it meets, the more opportunities there are for change.

The continual (and potential bi-directional) movement of viruses across oceans only increases those opportunities.

In 2023, what happens with HPAI in migratory birds and poultry in Asia and Europe is of greater concern for North and South America than ever before, as oceans are no longer the protective barrier we once thought.

Which is why we need to be prepared for surprises going forward.