Flu Virus binding to Receptor Cells – Credit CDC

#17,825

While we are continually on watch for novel strains of influenza A (like H5N1, H5N6, H3N8, etc.). even regular seasonal flu (H1N1 or H3N2) can sometimes pick up mutations that can make it more transmissible, more pathogenic, or evade antiviral medications.

Although these mutations can make seasonal flu more dangerous, it is believed that most of the time they add a performance penalty (in terms of transmissibility, infectivity, or replication) that limits their public health impact.

One we watch for is the H275Y mutation - a single amino acid substitution (histidine (H) to tyrosine (Y)) at the neuraminidase position 275 - which is linked to oseltamivir (aka Tamiflu (TM)) resistance. Luckily, most years it is only found in less than 1% of viruses sampled.

But in 2008 H275Y defied the odds, as the incidence of resistant seasonal H1N1 viruses literally exploded around the globe. In less than a year, the H1N1 virus had gone from 98% susceptible to oseltamivir to nearly 100% resistant.

By the end of 2008 the CDC was forced to issue major new guidance for the use of antivirals (see CIDRAP article With H1N1 resistance, CDC changes advice on flu drugs), and there were grave concerns going into 2009.

This pervasive spread of resistant H1N1 would have had a much bigger impact had it not been for the arrival of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus, which effectively supplanted the old (resistant) H1N1, and replaced it with a new – but fortunately, still susceptible to NAIs – H1N1 virus.

However the 2009 H1N1 pandemic brought attention to another mutation; D222G (D225G in influenza H3 Numbering), dubbed the `Norway mutation' by the press.

In late 2009 the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (see Norway Reports An H1N1 Mutation) announced the discovery of a mutation that “. . . could possibly make the virus more prone to infect deeper in the airways and thus cause more severe disease."

The D222G mutation involves a single amino acid change in the HA gene at position 222 from aspartic acid (D) to glycine (G). Over the next few months several additional variations on a theme were discovered; D222N, D222E, and D222A.

In January of 2010, the World Health Organization’s Weekly Epidemiological Record (No. 4, 2010, 85, 21–28) provided a detailed overview of what was then known about this rare mutation.

While stating that more study was needed, the WHO pointed out the lack of apparent ongoing transmission of this mutation, and stated that:

`Based on currently available virological, epidemiological and clinical information, the D222G substitution does not appear to pose a major public health issue.’

The debate over the significance (and origins) of the D222G mutation have continued since then. While the D222G is thought to occur mainly after a patient is infected with the H1N1 virus (aka a `spontaneous mutation'), there are always concerns that these viruses could become more transmissible.

Since then we've revisited the D222G/N mutation a number of times, including:

All of which brings us to a lengthy and detailed look at the 2022-2023 influenza season in Russia which featured the emergence of a new clade (6B.1A.5a.2a) of H1N1 (see also ECDC Influenza Characterisation Report - Feb. 2022), along with an analysis of fatal outcomes.

While the incidence of D222G/N in the wild is thought to be less than 1%, the viruses from 29% of the fatal cases in this study were found to carry this mutation.

Due to its length, and technical nature, I've only posted the link and some excerpts. Follow the link to read the report in its entirety.

I'll return after the break with a postscript on the `Mystery flu' of 1951.

An Investigation of Severe Influenza Cases in Russia during the 2022–2023 Epidemic Season and an Analysis of HA-D222G/N Polymorphism in Newly Emerged and Dominant Clade 6B.1A.5a.2a A(H1N1)pdm09 Viruses

by

Natalia P. Kolosova *,†,Nikita D. Boldyrev †,Svetlana V. Svyatchenko,Alexey V. Danilenko,Natalia I. Goncharova, Kyunnei N. Shadrinova, Elena I. Danilenko, Galina S. Onkhonova, Maksim N. Kosenko, Maria E. Antonets, Ivan M. Susloparov, Tatiana N. Ilyicheva, Vasily Y. Marchenko and Alexander B. Ryzhikov

State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector”, Rospotrebnadzor, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk 630559, Russia

Pathogens 2024, 13(1), 1; https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13010001 (registering DOI)

Abstract

In Russia, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a decrease in influenza circulation was initially observed. Influenza circulation re-emerged with the dominance of new clades of A(H3N2) viruses in 2021–2022 and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses in 2022–2023. In this study, we aimed to characterize influenza viruses during the 2022–2023 season in Russia, as well as investigate A(H1N1)pdm09 HA-D222G/N polymorphism associated with increased disease severity.

PCR testing of 780 clinical specimens showed 72.2% of them to be positive for A(H1N1)pdm09, 2.8% for A(H3N2), and 25% for influenza B viruses. The majority of A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses analyzed belonged to the newly emerged 6B.1A.5a.2a clade.

The intra-sample predominance of HA-D222G/N virus variants was observed in 29% of the specimens from A(H1N1)pdm09 fatal cases. The D222N polymorphic variant was registered more frequently than D222G.

All the B/Victoria viruses analyzed belonged to the V1A.3a.2 clade. Several identified A(H3N2) viruses belonged to one of the four subclades (2a.1b, 2a.3a.1, 2a.3b, 2b) within the 3C.2a1b.2a.2 group. The majority of antigenically characterized viruses bore similarities to the corresponding 2022–2023 NH vaccine strains. Only one influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus showed reduced inhibition by neuraminidase inhibitors. None of the influenza viruses analyzed had genetic markers of reduced susceptibility to baloxavir.

4.4.1. Detection of HA-D222G/N Polymorphism in A(H1N1)pdm09 Viruses from Fatal Cases

The targeted NGS approach showed that viral subpopulations with HA-D222G or D222N substitutions were predominant in 27 A(H1N1)pdm09 virus specimens originating from fatal influenza cases (29% of all A(H1N1)pdm09 fatal cases assessed for the intra-sample genetic diversity during the 2022–2023 season in Russia). In most of these cases (93%), the predominance of the D222N virus variants was identified.

Further analysis of NGS data showed that 14% of the fatal influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 cases were characterized by the predominance of the wild type 222D virus subpopulations in a sample with a 1–31.5% admixture of HA-D222G or/and D222N virus variants.

The comparable frequency of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses with D222G/N substitutions among influenza cases with fatal outcomes were registered in Russia during the 2018–2019 flu season. Particularly, D222G or D222N polymorphic virus variants prevailed in 32% of virus samples originating from fatal cases. In 25% of fatal cases, the predominating wild type virus variant coexisted with an admixture of D222G or/and D222N subpopulations comprising at least 1% of the total viral population [10].

In contrast to the 2022–2023 flu season, D222G polymorphic virus variants were registered more frequently than D222N variants during the 2018–2019 flu season in Russia. A similar high occurrence and predominance of viruses with the D222G substitution in severe influenza cases were also reported in Germany during the 2010–2011 flu season [46]. The observed inter-seasonal difference may indicate that the preferred accumulation of D222G or D222N substitutions may depend on the genetic background of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses circulating during a particular flu season.

Of the virus samples with the D222G/N substitutions registered during the 2022–2023 season, a substantial proportion contained viruses with both D222G and D222N variants (with a 5% or more proportion in the samples). Previous studies also reported the co-occurrence of D222G and D222N variants in A(H1N1)pdm09 virus samples from severe cases [10,11,12,46,47]. Such polymorphic virus populations could possibly lead to a more severe course of disease due to faster virus adaptation [48].

It is significant that the polymorphism in the HA of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses is very restricted to either D222N or D222G variants. Viruses with the predominant subpopulation bearing other substitutions, such as D222Y/E/A/V, are very rarely observed in severe cases. However, their association with the severity of the disease has not been shown and, as previously reviewed, their effect on virus properties has not been determined [9,10].

(SNIP)

5. Conclusions

A re-emergence of a large-scale circulation of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses was observed in Russia during the 2022–2023 flu season. It was characterized by the dominance of the new 6B.1A.5a.2a clade viruses, which were antigenically distinct from the 5a.1 A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses present in circulation prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Influenza B viruses, which also reentered wide circulation in 2022–2023, belonged to the new V1A.3a.2 clade.

A substantial number of A(H1N1)pdm09 virus samples (29%) from fatal influenza cases were predominated by subpopulations bearing HA-D222N or D222G amino acid substitutions, which may represent an important pathogenicity factor associated with severe influenza cases.

The return of influenza to epidemic-level circulation and the high rate of evolution of seasonal influenza viruses with the emergence of new antigenic clades and pathogenicity factors highlights the importance of monitoring seasonal influenza, including severe cases, with the aim of developing and optimizing prevention and treatment measures.

Although there is no evidence here of clustering of D222G/N cases, or community transmission, the authors warn:

Despite the currently observed limited representation of D222G/N polymorphism in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses in broad circulation, it is important to monitor the circulation of viruses with these substitutions and detect epidemiologically significant shifts in circulation and changes in virus properties, such as transmissibility and pathogenicity.

As an example of how unpredictable flu can be, nearly 6 years ago in Remembering 1951: The Year Seasonal Flu Went Rogue, we looked at an unusually deadly wave of seasonal influenza during an otherwise mild non-pandemic flu year.

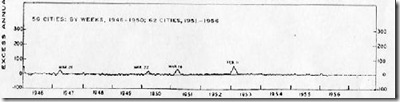

The winter of 1950-1951 had been an average flu year, with the dominant flu called the `Scandinavian strain', which produced mild illness in most of its victims. In fact, if you look at a graph of flu activity for the United States, running from 1945 to 1956, you'll see nary a blip.

But in December of 1950 a new strain of virulent influenza appeared in Liverpool, England, and by late spring, it had spread across much of England, Wales, and parts of Canada.

The following comes from an absolutely fascinating EID Journal article by Viboud C, Tam T, Fleming D, Miller MA, Simonsen L.

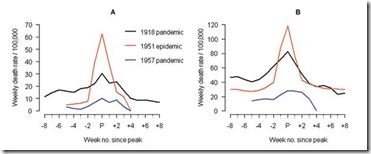

The 1951 influenza epidemic (A/H1N1) caused an unusually high death toll in England; in particular, weekly deaths in Liverpool even surpassed those of the 1918 pandemic. . . . . Why this epidemic was so severe in some areas but not others remains unknown and highlights major gaps in our understanding of interpandemic influenza.

According to this study, the effects on the city of origin, Liverpool, were horrendous.

In Liverpool, where the epidemic was said to originate, it was "the cause of the highest weekly death toll, apart from aerial bombardment, in the city's vital statistics records, since the great cholera epidemic of 1849" (5). This weekly death toll even surpassed that of the 1918 influenza pandemic (Figure 1)

For roughly 5 weeks Liverpool saw an incredible spike in deaths due to this new influenza. And it didn’t just affect Liverpool. While it appears not to have spread as easily as the dominant Scandinavian strain, it managed to affect large areas of England, Wales, and parts of Canada over the ensuing months.

Getting started relatively late in the flu season, this new strain never managed to spread much beyond UK and Eastern Canada. Nor did it reappear the following flu season. It simply vanished as mysteriously as it appeared.

Exactly what caused this wave to be so deadly remains a unknown, but it is reminder that even seasonal influenza can turn nasty with little or no warning.