#17,882

The origins of the next major global health crisis - what many health officials have dubbed as `Disease X' (a placeholder name, not a specific disease) - is completely unknown, but we can make some educated guesses as to its nature.

1st, it will be primarily a respiratory disease, spread via droplets or fine aerosols. We know that, because non-respiratory diseases (e.g. vector borne, or spread by direct contact) tend to produce regional, not global, outbreaks.

2nd, it will have the ability to be spread - as does influenza and COVID - from asymptomatic (or pre-symptomatic) carriers. The primary reason why the 2002-2003 SARS-CoV outbreak was contained was because it lacked this ability, which allowed for easier containment.

Lastly, nosocomial transmission will not only injure patients and healthcare workers, but degrade the ability of healthcare facilities to provide essential services during the crisis.

Even though we knew all of this before SARS-CoV-2 emerged, the world prepared for something far less formidable. After going nearly 100 years and seeing only infrequent and mild-to-moderate influenza pandemics, many planners simply assumed we were past the age of truly severe pandemics.

As a result, we were woefully unprepared for the pandemic we eventually got.

Our Strategic National Stockpile was far less well equipped than advertised, with warnings (see Caught With Our Masks Down) about inevitable PPE shortages and inadequate ventilators (see Pandemic Realities: Ventilator Shortages) having gone unheeded.

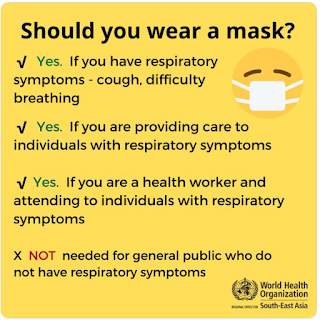

WHO pandemic guidance, published just months before the pandemic, recommended against the wearing of masks (of any type) by the public (see graphic below); a policy which remained in place until the summer of 2020.

The following infamous Feb 29th, 2000 tweet by the U.S. Surgeon General also sought to discourage the use of masks by the general public.

Even though the airborne spread of COVID was becoming increasingly obvious (see COVID-19: The Airborne Division), officially it remained primarily a `droplet' infection, and many healthcare facilities relied on (cheaper, and more readily available) surgical masks to protect their staff and patients.

The World Health Organization's recommendations for PPE for HCWs in contact with COVID cases recommended the wearing of `medical masks' defined as `surgical or procedure masks that are flat or pleated (some are like cups); they are affixed to the head with straps'.

Last night CIDRAP published a lengthy review of the debate (see link and excerpts below), which includes quotes from a number of well known public health experts. Follow the link to read it in its entirety, I'll have a bit more after the break.

Updated WHO COVID prevention guidance may endanger rather than protect, some experts say

Mary Van Beusekom, MS

January 26, 2024

COVID-19

The World Health Organization's (WHO's) newly updated COVID-19 prevention and control guidelines purport to protect healthcare workers, patients, and the community, but some experts say they may encourage risky behavior by propagating long-disproven ideas about how viruses spread.

"I think they put healthcare workers and patients and the community at significant risk," said Lisa Brosseau, ScD, CIH, an expert on respiratory protection and infectious diseases and a CIDRAP research consultant.

One of the main problems, said Raina Macintyre, MBBS, PhD, professor and head of the biosecurity program at the Kirby Institute in Sydney, Australia, is that the document doesn't incorporate many of the lessons learned during the pandemic—such as the major role of COVID-19 spread among people with no symptoms.

"The guidelines suggest using symptoms to screen people," she said via email. "This is seen in health guidelines in many countries—emphasis on symptoms ('wear a mask if you feel unwell'), when we know a substantial proportion of transmission is asymptomatic, which is a major rationale for universal masking in high-transmission settings."

I know a lot of health care workers felt betrayed by the lack of PPEs during the opening months of the COVID pandemic. It was very much a repeat (only worse) of the opening months of the relatively mild 2009 H1N1 pandemic, when sporadic PPE shortages were reported (see California Nurses Association Statement On Lack Of PPE).

In the wake of those shortages, we saw numerous calls for better pandemic preparedness, including:

- In 2009 the Minnesota Center for Health Care Ethics and University of Minnesota Center for Bioethics released draft ethical pandemic guidelines on the rationing of scarce resources, where they estimated their were only enough PPE’s in the state of Minnesota to last 3 weeks into a severe pandemic.

- In 2014 in NIOSH: Options To Maximize The Supply of Respirators During A Pandemic, we looked at strategies to try and cope with the expected shortfall in PPEs during a severe pandemic.

- A 2015 CID Journal report Potential Demand for Respirators and Surgical Masks During a Hypothetical Influenza Pandemic in the United States estimated in the U.S. alone, we'd need billions of respirators and masks.

But despite countless promises and having a full decade to prepare, when COVID emerged, the cupboards were nearly bare for both types of PPEs.

While I'd like to believe the last 4 years have taught us the folly of underestimating pandemic threats, and the need for maintaining robust pandemic preparedness, the evidence suggests otherwise.

We no longer report COVID hospitalizations or deaths, and seek to minimize its risks at every turn, despite ample evidence of `Long COVID' and the potential for seeing more dangerous variants emerge in the future.

Whether we are faced with a new pandemic threat, or a emergence of a new COVID variant, health care and other front line workers are deserving of the best gear, and guidance, that we can provide.

Not the least we can get away with.