Zhejiang Province – Credit Wikipedia

#17,908

Two weeks ago, in China NHC Statement: A Fatal Case of H3N2 and H10N5 Mixed Infection Discovered in Zhejiang Province, we looked at a fatal avian/seasonal flu coinfection reported out of China.

Cases such as this, while believed rare, probably occur more often than we know, as it requires a bit of luck for them to be detected and/or reported.

Mild or moderate infections - or even fatal ones in facilities or regions with less thorough testing - are far less likely to be picked up by surveillance.

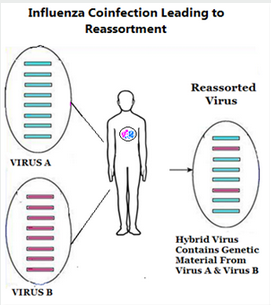

Co-infections in humans - or in any other susceptible host (birds, pigs, etc.) - are a concern because it can allow two (or more) influenza viruses to swap genetic material (reassort) producing a hybrid virus.

While most of these reassortments are destined to become evolutionary failures, every once in a while a reassortment produces a `biologically fit' virus able to compete, and sometimes even thrive. Twice in my lifetime (1957 and 1968) avian flu viruses have reassorted with seasonal flu and launched a human pandemic.

- The first (1957) was H2N2, which According to the CDC `. . . was comprised of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes.'

- In 1968 an avian H3N2 virus emerged (a reassortment of 2 genes from a low path avian influenza H3 virus, and 6 genes from H2N2) which supplanted H2N2 - killed more than a million people during its first year - and continues to spark yearly epidemics more than 50 years later.

Unlike HPAI H5 and H7 viruses, H10 (and many other LPAI HA subtypes) are not `legally reportable' to the OIE, meaning that we don't have a very good handle on how prevalent they may be in captive birds, or in the wild.

In 2014's BMC: H10N8 Antibodies In Animal Workers – Guangdong Province, China, we saw evidence that some people may have been infected with the H10N8 virus in China long before their first case was recognized in late 2013.

In today's report, we learn of a second stroke of luck; investigators were able to detect the H10N5 virus in duck meat stored in her fridge since November of last year. No other cases have been identified, and apparently no outbreaks of H10 have been reported in local poultry.

Due to its length, I've only posted some excerpts from the update/risk analysis. Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a postscript after the break.

Avian Influenza A(H10N5) and Influenza A(H3N2) coinfection - China

13 February 2024

Situation at a Glance

On 27 January 2024, the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of one confirmed case of human coinfection with avian influenza A(H10N5) virus and seasonal influenza A(H3N2) virus. This is the first case of human infection with avian influenza A(H10N5) virus reported globally.

The case occurred in a female farmer over 60 years of age, with a history of chronic comorbidities, from Xuancheng Prefecture, Anhui Province. She had onset of symptoms on 30 November 2023 and passed away on 16 December 2023. The authorities isolated seasonal influenza A(H3N2) subtype and avian influenza A(H10N5) subtype viruses from the patient’s samples on 22 January 2024, which were affirmed in confirmatory testing on 26 January 2024.

The patient had exposure to live poultry, and poultry samples also tested positive for H10N5. No new suspected human cases have been detected through the investigation and testing done by authorities. Currently available epidemiologic information suggests that avian influenza A(H10Nx) viruses have not acquired the capacity for sustained transmission among humans. Thus, the likelihood of human-to-human spread is considered low.

Description of the Situation

On 27 January 2024, the National Health Commission of the Peoples Republic of China notified WHO of one confirmed case of human coinfection with influenza A(H10N5) virus and seasonal influenza A(H3N2) virus. This is the first case of human infection with avian influenza A(H10N5) virus reported globally.

The case occurred in a female farmer over 60 years of age from Xuancheng Prefecture, Anhui Province, who had onset of symptoms of cough, sore throat and fever on 30 November 2023. The patient, who had a history of chronic comorbidities, was admitted to a local hospital on 2 December 2023 for treatment and was then transferred on 7 December 2023 to a medical institution in Zhejiang Province as her condition became more severe. The patient was diagnosed with influenza A virus infection. She passed away on 16 December 2023. Zhejiang Province health officials isolated seasonal influenza A(H3N2) subtype and avian influenza A(H10N5) subtype viruses from the patient’s samples on 22 January 2024 after nucleic acid testing, viral culture and gene sequencing conducted by local health care facilities.

On 26 January 2024, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention conducted confirmatory testing on the samples from Zhejiang Province and verified the laboratory results. It was noted that the patient had not been vaccinated for seasonal influenza.

The patient had exposure to live poultry through the purchase of a duck on 26 November 2023. From the duck meat stored in the fridge, seven samples tested positive for H10N5, and two samples were positive for N5 (no result for haemagglutinin). The patient had no contact with pigs or other mammals. Environmental samples were collected from her home, and all tested negative.

Medical observation of all close contacts in Zhejiang and Anhui provinces has found no additional suspected cases. Retrospective case finding activities also did not identify any other cases during the same period.

(SNIP)

WHO Risk Assessment

Most human cases of infection with avian influenza viruses reported to date have been due to exposure to infected poultry or contaminated environments.

The first A(H10) subtype was isolated from chickens in Germany in 1949. Since then, A(H10) strains have occasionally been detected in wild waterfowl, domestic poultry, and mammals worldwide. As the A(H10) viruses are low pathogenic avian influenza viruses, it is not required to be reported to the World Organisation for Animal Health, and therefore, their true prevalence is unknown.

In 2008, avian influenza A(H10N5) was isolated from swine in Hubei, China; however, the current H10N5 infection in a human in China is the first human case of avian influenza A(H10N5) detected globally.

Due to limited data, further research is needed to determine the epidemiology of H10N5 viruses among animal populations to help inform surveillance efforts and preventive measures. Surveillance is important to monitor the spread of the virus, particularly in bird populations, considering the sporadic nature of human infections with other H10Nx subtypes such as H10N3.

Currently available epidemiologic information suggests that avian influenza A(H10Nx) viruses have not acquired the capacity for sustained transmission among humans. Thus, the likelihood of human-to-human spread is considered low. Should infected individuals from affected areas travel internationally, their infection may be detected in another country during travel or after arrival. If this were to occur, further community-level spread is considered unlikely.

WHO Advice

The public should avoid high-risk environments, such as live animal markets or farms, and avoid contact with live poultry or surfaces that might be contaminated by birds or poultry droppings. Hand hygiene with frequent handwashing or using alcohol-based hand sanitizer is recommended.

Due to the constantly evolving nature of influenza viruses, WHO continues to stress the importance of global surveillance to detect virological, epidemiological, and clinical changes associated with circulating influenza viruses that may affect human (or animal) health, and timely virus sharing for risk assessment.

All human infections caused by a new subtype of influenza virus are notifiable under the International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005). States Parties to the IHR (2005) are required to immediately notify WHO of any laboratory-confirmed case of a recent human infection caused by an influenza A virus with the potential to cause a pandemic. Evidence of illness is not required for this report.

WHO does not recommend any specific measures for travelers. WHO does not recommend any travel and/or trade restrictions toward China based on the currently available information.

(Continue . . . )

Live bird markets (LBMs) have long been linked to human exposure to (and infection by) avian influenza viruses, so much so that in 2014, in CDC: Risk Factors Involved With H7N9 Infection, we looked at a case-control study that pretty much nailed visiting LBMs as the prime risk factor for infection.

Since then we've seen cases whose likely exposures were cited as simply living near, or walking past an LBM (see J. Infection: Aerosolized H5N6 At A Chinese LBM (Live Bird Market)).

While China and other governments have attempted to shut down these markets (see Beijing Orders Closure Of Live Bird Markets To Control H7N9), they are so deeply ingrained in many cultures that illegal markets quickly spring up in their place.

Legal markets can be inspected and regulated, which is why LBMs are still tolerated and most bans have been short-lived.

All of which makes the WHO advice to `avoid high-risk environments, such as live animal markets' technically sound, but unlikely to have much impact. Which is great news, I suppose, if you are a virus.

But not so great if you are a host.