#18,070

Not quite two weeks ago we saw a preprint reporting the detection of avian H5N1 in wastewater from 9 (unnamed) Texas cities - starting last March - whose rate exceeded that of seasonal influenza viruses by April.

While the origins of these viruses are still thought to be primarily from avian or bovine sources, some contributions from humans cannot be excluded.

A week ago the CDC unveiled - and last Friday updated - their own wastewater surveillance dashboard; one that samples up to 674 facilities, but only measures influenza A activity. In other words, it does not identify individual subtypes like H5.

The CDC's latest update, however, does show an unexpected increase in influenza A virus detection (see maps below) in a small number of cities.

With HPAI H5N1 spreading in cattle across multiple states, and the potential for spillovers to other mammals (including humans), what is desperately needed is a nationwide wastewater surveillance system that can discriminate between seasonal influenza and novel subtypes.

While that still might not tell us the source of the virus, it would tell us a lot more about the scope of the the problem, and that could tell public health officials where they should be concentrating their testing resources.

Yesterday the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters published a report from the research team at @WastewaterSCAN which found additional evidence of H5 in wastewater solids in 4 facilities in communities (in Texas and North Carolina) reporting H5N1.

As a control, they also tested wastewater on the island of Hawaii - where H5N1 has not been reported in cattle - and those results were negative.

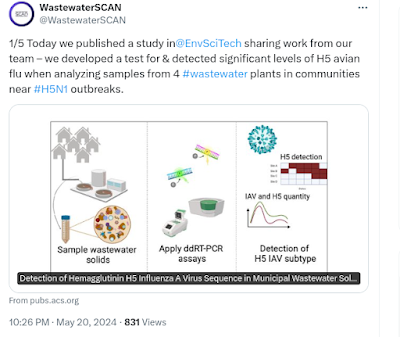

First an overview, from their twitter feed.

The full report is lengthy, but well worth reading. I've only posted some excerpts, so follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a brief postscript after the break.

Detection of Hemagglutinin H5 Influenza A Virus Sequence in Municipal Wastewater Solids at Wastewater Treatment Plants with Increases in Influenza A in Spring, 2024Marlene K. Wolfe, Dorothea Duong , Bridgette Shelden, Elana M. G. Chan, Vikram Chan-Herur,Stephen Hilton, Abigail Harvey Paulos,Xiang-Ru S. Xu, Alessandro Zulli, Bradley J. White , and Alexandria B. Boehm*

Cite this: Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2024, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX

Publication Date:May 20, 2024

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.4c00331

© 2024 The Authors. Published by American Chemical Society. This publication is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Abstract

Prospective influenza A (IAV) RNA monitoring at 190 wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) across the US identified increases in IAV RNA concentrations at 59 plants in spring 2024, after the typical seasonal influenza period, coincident with the identification of highly pathogenic avian influenza (subtype H5N1) circulating in dairy cattle in the US. We developed and validated a hydrolysis-probe RT-PCR assay for quantification of the H5 hemagglutinin gene. We applied it retrospectively to samples from four WWTPs where springtime increases were identified and one WWTP where they were not.

The H5 marker was detected at all four WWTPs coinciding with the increases and not detected in the WWTP without an increase. Positive WWTPs are located in states with confirmed outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, in dairy cattle. Concentrations of the H5 gene approached overall influenza A virus gene concentrations, suggesting a large fraction of influenza virus inputs were H5 subtypes. At all four H5 positive WWTPs, industrial discharges containing animal waste, including milk byproducts, were permitted to discharge into sewers.

Our findings demonstrate that wastewater monitoring can detect animal-associated influenza contributions and highlight the need to consider industrial and agricultural inputs into wastewater. This work illustrates wastewater monitoring’s value for comprehensive influenza surveillance, including for influenzas that currently are thought to be primarily found in animals with important implications for animal and human health.

Wastewaterscan.org is based at Stanford University, in partnership with Emory University, and their public dashboard (see below) currently provides recent and historical information on the detection of 12 different pathogens.(SNIP)

Discussion

H5 influenza RNA was readily detected in wastewater solids at sites in TX and NC with atypical increases in influenza A M gene concentrations in March and April 2024 during a period of a known H5N1 outbreak in the US. The presence of H5 in municipal wastewater indicates that contributions into the wastewater system include excretions or byproducts containing influenza viral RNA with an H5 subtype, but do not indicate the species that may be shedding an H5 influenza. During March and April 2024, increases in IAV M gene concentrations at the TX and NC WWTPs were not coincident with increases in human influenza activity (personal communication, local health officers, and documented by state positivity rate data). However, both the increases in M gene concentrations and H5 detection occurred immediately prior to and during reported outbreaks of H5N1 in dairy cattle in the regions. (16) These results suggest that wastewater monitoring is a viable method of monitoring certain animal pathogens, and can provide a leading edge of detection that is of particular importance for diseases with zoonotic potential like HPAI.

Hypothesized Sources of H5H5N1 outbreaks in dairy cattle were reported on 3/25/24 in the Texas panhandle, (32) which contains the City of Amarillo and on 4/9/24 in North Carolina. (16) There was also a human case of H5N1 reported in Amarillo in an individual who worked at a commercial dairy cattle farm and reported close proximity to dairy cows. (7) Amarillo, Dallas County, and Forsyth County WWTPs receive discharges from industries handling Animal by-products, including dairies that receive milk from across the region and beef processing plants (personal communication from local staff). Dairy cattle have been reported to shed H5N1, as well as other viruses, in milk in high quantities. (33,34) During the current outbreak, H5N1 nucleic-acids have been detected in both raw and pasteurized milk. (35) Pasteurization is expected to inactivate the virus, although it may still be detectable as noninfectious genetic material can persist past pasteurization. (36) Regardless of whether milk or milk products entering the sewer system have undergone pasteurization or pretreatment before they are discharged, our methods detect viral nucleic acids, although importantly their detection does not imply viability - this was not within the remit of the current study. Note that since these WWTPs are separate sanitary sewer systems, inputs of agricultural runoff or farm waste are not expected.

Given the outbreaks in dairy milking cattle in the region, (16) reports of H5N1 shedding in cow milk and detection in milk products on the shelf, and animal industry contributions into wastewater at the four WWTPs, we hypothesize that dairy processing discharge into the sewage system is driving the detection of H5 identified in wastewater solids. The lack of detection of the H5 marker in Hawai’i where there are no documented HPAI infections in animals, no dairy processing discharge, and no evidence of springtime increases in the IAV M gene supports this hypothesis.

It is important to note that, even if true, this does not eliminate the possibility of contributions from other animals, including humans. If dairy industry activities in sewersheds are a primary source of H5 in wastewater, this suggests that there may be additional, unidentified outbreaks among cattle with milk sent to these facilities since milk from infected animals is required to be diverted from food supply. Select lift station and industrial discharge sampling in the Amarillo sewersheds identified H5 marker in discharge from a dairy processing plant, but also at lift stations that contained wastewater from primarily residential and retail areas (see SI, Figure S5). While we note that these samples are not directly aligned with samples from the corresponding utilities, this evidence supports the hypothesis of significant dairy contributions, as well as the likelihood of multiple sources to the WWTPs.