Cats As Potential Vectors/Mixing Vessels for Novel Flu

#18,046

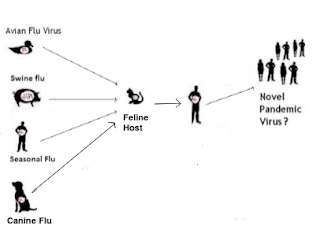

One of the topics we revisit with some frequency in this blog is the potential for companion animals (primarily cats) to serve as mixing vessels, and potential conduits of avian influenza to humans (see A Brief History Of Avian Influenza In Cats).

While only rarely documented, it is not an idle concern.

In late 2016, New York City reported that hundreds of cats across several city-run animal shelters contracted avian an LPAI H7N2 (see NYC Health Dept. Statement On Avian H7N2 In Cats).

Studies later showed that two shelter workers were infected while 5 others exhibited low positive titers to the virus, suggesting possible infection (see J Infect Dis: Serological Evidence Of H7N2 Infection Among Animal Shelter Workers, NYC 2016).

Over the years we've looked at dozens of other cat-related spillovers, including these recent reports:

Emerg. Microbes & Inf.: Characterization of HPAI A (H5N1) Viruses isolated from Cats in South Korea, 2023

To these we can add recent reports of cats in close proximity to H5N1 infected dairy cattle succumbing to the virus after presenting with severe neurological manifestations. That, along with other recent reports, led the CDC to issue Guidance for Veterinarians: Evaluating & Handling Cats Potentially Exposed to HPAI H5N1.

Two decades ago, it was assumed that cats were not particularly susceptible to influenza A infection, but today we know they can even catch seasonal flu from humans (see I&ORD: Evidence of Reverse Zoonotic Transmission of Human Seasonal Influenza A Virus (H1N1, H3N2) Among Cats).

All of which brings us to a preprint which conducts a review of the literature going back to 2004 (when the first spillover of H5N1 to Asia Tigers was reported), and finds hundreds of documented cat infections and deaths, with a substantial uptick in reports since 2023.

Due to its length I've only posted the link, abstract, and some excerpts. Follow the link to read the report in its entirety. I'll have postscript after the break.

Avian Influenza Virus Infections in Felines: A Systematic Review of Two Decades of LiteratureKristen K. Coleman, Ian G. Bemisdoi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.30.24306585

As an avian influenza virus panzootic is underway, the threat of a human pandemic is emerging. Infections among mammalian species in frequent contact with humans should be closely monitored. One mammalian family, the Felidae, is of particular concern.Felids, known as felines or cats, are susceptible to avian influenza virus infection. Felines prey on wild birds and may serve as a host for avian influenza virus adaptation to mammals. Feline-to-feline transmission has been demonstrated experimentally [1], and real-world outbreaks have been reported [2,3]. Domestic cats are a popular human companion animal and thus provide a potential pathway for zoonotic spillover of avian influenza viruses to humans.Here, we provide a systematic review of the scientific literature to describe the epidemiology and global distribution of avian influenza virus infections in felines reported from 2004 – 2024. We aim to provide a comprehensive background for the assessment of the current risk, as well as bring awareness to the recurring phenomenon of AIV infection in felines.

(SNIP)

Avian influenza virus infections in felines reported over time The annual number of articles reporting avian influenza infections in felines drastically increased in 2023 (Figure 2), with a recent spike in the total number of domestic cat infections reported in 2023 and 2024 (Figure 3) from multiple regions (Supplementary Figure 1).

This spike is commensurate with the emergence and increased spread of avian influenza virus H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b among birds and mammals. As publication year may not be representative of the actual year(s) in which reported feline infections occurred, we provide data on the specific year(s) each study took place (Table 1). The overall case fatality rate among the reported RT-PCR-confirmed feline infections identified in our review was estimated to be 63%.

Among the publications that described the illness experienced by the reported feline infections, respiratory and neurological illness were the most common and often resulted in death. Blindness and chorioretinitis were also recently observed in two AIV-infected domestic cats exposed to the virus through drinking raw colostrum and milk containing high viral loads from infected dairy cattle [5]. This clinical observation was unique to these feline cases and suggests that exposure route and dose of AIV might impact disease presentation and severity.

Among all the reported feline infections, highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) was the most frequently identified subtype, followed by H5N6, H7N2, H9N2, and H3N8. H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b was first detected in felines in 2022, including a wild lynx during an outbreak among pheasants in Finland [24], and a domestic cat living near a duck farm in France [25].

All studies reporting feline infections occurring since that time have identified H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b as the causative agent [4,26–32], aside from one serology study in Spain which did not report the specific clade of the H5 virus identified [33]. Overall, clade 2.3.4.4b accounted for 112 of the reported feline cases and 75 deaths, yielding a mortality rate of 67%

Discussion and Conclusion

Through our systematic review, we identified 486 avian influenza virus infections in felines, including 249 associated feline deaths, reported in the English scientific literature from 2004 – 2024. The reports represent cases from 7 geographical regions, including 17 countries and 12 felid species.Of particular interest are domestic cats infected with H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4, which represents a variant in the hemagglutinin serotype 5 gene of IAV which became the dominant IAV H5 serotype among poultry in 2020 [35]. Clade 2.3.4.4b was first reported in felines in 2022, and among the feline infections reported, it has yielded a mortality rate of 67%.Clade 2.3.4.4b is also responsible for the ongoing AIV outbreaks among dairy cattle in the U.S. [5], representing a significant threat to feline companion animals. Furthermore, subclinical infections of H5N1 in cats have been reported [6].Thus, we argue that surveillance among domestic cats is urgently needed. As feline-to-human transmission of AIV has been documented [2,3], farm cat owners, veterinarians, zoo keepers, and cat shelter volunteers may have a heightened risk of AIV infection during outbreaks among poultry and mammalian farm animals.

While dogs are also susceptible to H5N1 (see Microorganisms: Case Report On Symptomatic H5N1 Infection In A Dog - Poland, 2023), they tend to have milder (often asymptomatic) infections. Both, however, are believed capable of serving as `mixing vessels' for the virus.

We recently reviewed the CDC's Updated Advice On Bird Flu in Pets and Other Animals, which warned the public to avoid contact between their pets (e.g., pet birds, dogs and cats) with wild birds.