- The `herd data' has been dropped another layer `deeper' making it harder to find.

- The total number of herds infected has inexplicably dropped from 116 yesterday morning to 112 last night (see comparison graphic above)

- The map/data defaults (and when refreshed, reverts) to the `last 30 days'

- And I've had problems selecting & downloading the CSV files.

Admittedly, if I had more faith in the numbers being provided by the USDA, I'd be more concerned about this disparity. But testing of cattle across the country remains limited, and voluntary, and the number of herds actually infected is likely far greater than either number.

This site had intermittent problems before this upgrade, with tables not loading for more than 24 hours earlier this week, so an upgrade was sorely needed. Hopefully they'll work out the bugs in the days ahead.

Meanwhile the CDC has published their latest weekly update on their bird flu response (see below), which provides some preliminary information of receptor binding tests on the A/Texas/37/2024 strain, which was retrieved from the first human infection in Texas.

A few notes:

- First, curiously the CDC's count of herds affected is 118, not 112 as reported above by the USDA.

- Second, despite their increasing spillover into mammalian species, avian influenza viruses like H5N1 and H5N6 still bind preferentially to the alpha 2,3 receptor cells found in the gastrointestinal tract of birds.

- Humanized’ flu viruses - like seasonal H3N2 and H1N1 - have a strong affinity for the alpha 2,6 receptor cells most commonly found in the human respiratory system.

- While other mammalian adaptations are certainly required, the ability of avian flu viruses to bind to human α2-6 receptor cells is considered the single biggest obstacle the virus must overcome in order to successfully spread in humans.

- While greatly outnumbered by alpha 2,6 receptor cells, humans do have some of these avian-like alpha 2,3 receptor cells (particularly deep in the lungs), which likely explains how some avian viruses have jumped sporadically to humans (see Sialic Acid Receptors: The Key to Solving the Enigma of Zoonotic Virus Spillover).

CDC A(H5N1) Bird Flu Response Update June 21, 2024

AT A GLANCE

CDC provides an update on its response activities related to the multistate outbreak of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus, or "H5N1 bird flu," in dairy cows and other animals in the United States.

CDC Update

June 21, 2024 – CDC continues to respond to the public health challenge posed by a multistate outbreak of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus, or "H5N1 bird flu," in dairy cows and other animals in the United States. CDC is working in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), state public health and animal health officials, and other partners using a One Health approach. To date, there have been 3 human cases associated with an ongoing multistate outbreak of A(H5N1) in U.S. dairy cows. A Based on the information available at this time, CDC's current H5N1 bird flu human health risk assessment for the U.S. general public remains low. All three sporadic cases had direct contact with sick cows. On the animal health side, USDA is reporting that 118 dairy cow herds in 12 U.S. states have confirmed cases of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infections in dairy cows as the number of infected herds continues to grow.

Among other activities previously reported in past spotlights and still ongoing, recent highlights of CDC's response to this include:

- Posting an appendix to CDC's interim H5N1 bird flu guidance to categorize the degree of risk among people at higher risk of exposure based on specific activities, from highest to lowest risk. This information will help public health officials and clinicians as they work with farm workers to assess risk and implement monitoring, treatment and testing recommendations.

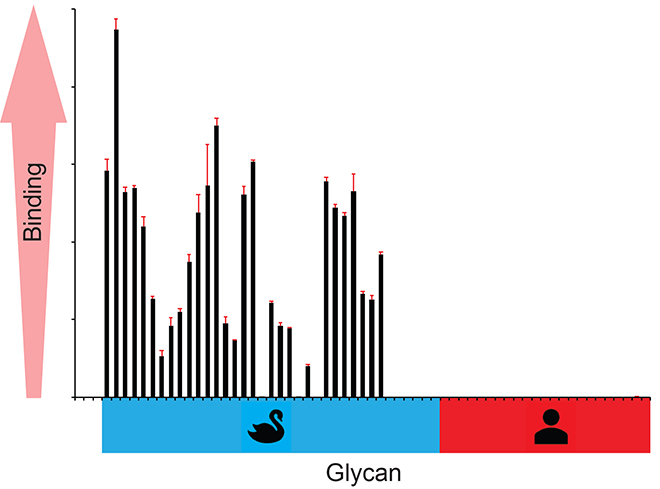

- Looking at the receptor binding profiles of recent avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses to see how well-adapted they are to causing infections in people (compared to birds). Humans and birds have different types and distributions of receptors to which influenza viruses can bind and cause infection. The hemagglutinin protein is responsible for the virus binding (or attaching) to host cells, which has to happen in order for infection to occur. For the receptor binding analysis of A/Texas/37/2024, the hemagglutinin (HA) surface protein of the virus was expressed in the lab and tested for its ability to bind to both human- and avian-type receptors. Preliminary results from these studies show that the A/Texas/37/2024 hemagglutinin only binds to avian-type receptors, and not to human-type receptors. This means the virus's HA has not adapted to be able to easily infect people.

How well the A(H5N1) virus HA binds to avian-type, but not to human-type receptors is shown in the graph. Results from these studies indicate that this virus maintains a preference for avian-type receptors and is not adapting to be able to infect people.

- Continuing to support strategies to maximize protection of farm workers, who are at higher risk of infection based on their exposures. This includes outreach to farm workers in affected counties through Meta (Facebook and Instagram), digital display, and audio (Pandora). These resources provide information in English and Spanish about potential risks of A(H5N1) infection, recommended preventive actions, symptoms to be on the look-out for, and what to do if they develop symptoms. Since May 30, when English assets launched, Meta outreach has generated more than 3 million impressions. Spanish Meta assets launched on June 6, and since then have garnered nearly 400,000 impressions. Additionally, CDC continues to create additional materials, including fact sheets in K'iche' and Nahuatl, in addition to Spanish.

- Continuing to support states that are monitoring people with exposure to cows, birds, or other domestic or wild animals infected, or potentially infected, with avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses. To date, more than 690 people have been monitored as a result of their exposure to infected or potentially infected animals, and at least 51 people who have developed flu-like symptoms have been tested as part of this targeted, situation-specific testing. Testing of exposed people who develop symptoms is happening at the state or local level, and CDC conducts confirmatory testing. More information on monitoring can be found at Symptom Monitoring Among Persons Exposed to HPAI.

- Continuing to monitor flu surveillance data using CDC's enhanced, nationwide summer surveillance strategy, especially in areas where A(H5N1) viruses have been detected in dairy cows or other animals for any unusual trends, including in flu-like illness, conjunctivitis, or influenza virus activity.Overall, for the most recent week of data, CDC flu surveillance systems show no indicators of unusual flu activity in people, including avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses.

This `fog of flu' does little to bolster confidence in either the message or the messenger.

While I'm not convinced the B3.13 genotype will be the spark that ignites the next pandemic, our inability to contain (or even reasonably quantify) this cattle epizootic bodes poorly should another, more formidable, virus come along.

Because in time - ready or not - another one will.