#18,308

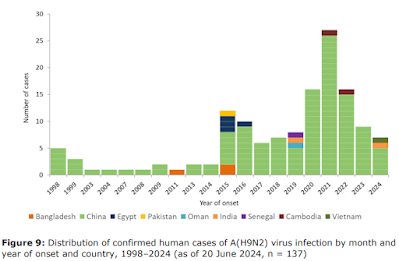

Although it ranks relatively low on our pandemic watch list, over the past 26 years we've seen nearly 140 H9N2 human infections officially reported from around the globe, with roughly 90% of those coming from China (see ECDC chart below).Often - particularly from China - we only get a smattering of details, such as the cryptic announcement earlier this week by Hong Kong's CHP of a recent case in Guangdong Province.

Most known cases have been mild or moderate, and occur predominantly in small children, but earlier this year we saw a severe case in an adult in Vietnam, and in 2021 a fatal outcome in a 39-year old male in China.

H9N2 infection is likely under reported, since the virus is widespread across Asia, and has made inroads into the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa; all regions where testing and surveillance are likely to be sub-optimal.

While we've seen a handful of H9N2 cases in Africa (4 in Egypt, 1 in Senegal), today's report is the first from Ghana. The patient, a 5 year-old boy, reportedly had no contact with poultry or anyone with influenza-like symptoms.It isn't clear from this report why this case - which according to the narrative originally tested positive for H3N2 - was given additional scrutiny and retested, yielding the H9N2 diagnosis.

Due to its length, I've only posted some excerpts from the WHO report. Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a brief postscript after the break.

Avian Influenza A(H9N2) - Ghana

20 September 2024

Situation at a glance

On 26 August 2024, the International Health Regulations (IHR) National Focal Point (NFP) for Ghana notified the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the country's first reported human case of infection with a zoonotic (animal) influenza virus. Subsequent laboratory tests confirmed the presence of the avian influenza A(H9N2) virus. According to epidemiological investigations, the patient, under five years old, had no known history of exposure to poultry or any sick person with similar symptoms prior to the onset of symptoms.The Ghanaian government has implemented a series of measures aimed at monitoring, preventing, and controlling the situation. According to the IHR (2005), a human infection caused by a novel influenza A virus subtype is an event that has the potential for high public health impact and must be notified to the WHO. Based on currently available information, WHO assesses the current risk to the general population posed by A(H9N2) viruses as low, but is continuing to monitor these viruses and the situation globally.

Description of the situation

On 26 August 2024, the Ghana IHR NFP notified WHO of one confirmed human infection with an avian influenza A(H9N2) virus. This marks the first human infection with a zoonotic influenza virus reported from Ghana to WHO.

The patient is a child under five years old, residing in the Upper East region, which is located on the border with Burkina Faso.

The onset of the illness occurred on 5 May 2024, characterized by a sore throat, fever, and cough. On 7 May, the patient was seen at a local hospital, received a diagnosis of influenza-like illness, and was treated with antipyretics, antihistamines and antibiotics.

Respiratory samples collected on 7 May, tested positive for seasonal influenza A(H3N2) virus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on 15 May at the Ghana National Influenza Centre (NIC), Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research.

On 9 July, genomic sequence analysis conducted by the Ghana NIC indicated an avian influenza A(H9) virus. Subsequently, an aliquot of the sample was dispatched to WHO Collaborating Centres (CC) located in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (The Francis Crick Institute) and the United States of America (the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US CDC), for additional testing and validation. On 6 August, the US CDC confirmed the samples as positive for influenza A(H9N2) virus.

Upon confirmation of the A(H9N2) virus infection, the Upper East Regional Health Directorate visited the patient and observed that they were experiencing a new onset of respiratory symptoms. Serum and respiratory specimens were obtained on that day and sent to the NIC for further analysis. The test results were negative for influenza and the patient has since fully recovered.

The patient had no known history of exposure to poultry or any sick person with similar symptoms prior to onset of symptoms. Respiratory samples from close contacts tested negative for influenza. No additional cases of human infection with influenza A(H9N2) viruses associated with this case have been identified in the community.

Illness among poultry has been reported in the Upper East Region, but the cause of the poultry disease had not been confirmed at the time of reporting. However, influenza A(H9N2) low pathogenicity avian influenza viruses have been reported in Ghanaian poultry farms since November 2017.

Epidemiology

Animal influenza viruses normally circulate in animals but can also infect humans. Infections in humans have primarily been acquired through direct contact with infected animals or contaminated environments. Depending on the original host, influenza A viruses can be classified as avian influenza, swine influenza, or other types of animal influenza viruses.

Avian influenza virus infections in humans may cause mild to severe upper respiratory tract infections and influenza-associated deaths have been reported in persons with or without comorbidities. Conjunctivitis, gastrointestinal symptoms, encephalitis and encephalopathy have also been reported.

Laboratory tests are required to diagnose human infection with influenza. WHO periodically updates technical guidance protocols for the detection of zoonotic influenza using molecular methods, for example PCR.WHO risk assessment

This is the first human case of infection with a zoonotic influenza virus notified by Ghana. Laboratory testing confirmed the virus as an influenza A(H9N2) virus.

The majority of human infections with A(H9N2) viruses occur due to contact with infected poultry or environments that have been contaminated and typically result in mild clinical symptoms. Further human cases in persons with exposure to the virus in infected animals or through contaminated environments can be expected since the virus continues to be detected in poultry populations. To date, there has been no reported sustained human-to-human transmission humans of A(H9N2) viruses.

The existing epidemiological and virological evidence suggests that this virus has not acquired the capacity for sustained transmission among humans. Thus, the likelihood of sustained human-to-human spread is low. Should infected individuals from affected areas travel internationally, their infection may be detected in another country during travel or after arrival. However, if this occurs, further community-level spread is considered unlikely.

Hopefully more information will be forthcoming.

The CDC has designated 2 different lineages (A(H9N2) G1 and A(H9N2) Y280) for their short list of influenza viruses with zoonotic potential (see CDC IRAT SCORE), and several candidate vaccines have been developed.

H9N2's greatest claim to fame, however, is its ability to reassort with other - sometimes far more worrisome - viruses. Often, when new HPAI flu strains emerge – if you look deep enough – you’ll find LPAI H9N2 was part of the process (see EID Journal: Natural Reassortment of EA H1N1 and Avian H9N2 Influenza Viruses in Pigs, China).

Six years ago, in EID Journal: Two H9N2 Studies Of Note, we looked at two reports which suggested that H9N2 continues to evolve away from current (pre-pandemic and poultry) vaccines and is potentially on a path towards better adaptation to human hosts.

Last fall, in BMJ Global: Historical Trends Demonstrate a Pattern of Increasingly Frequent & Severe Zoonotic Spillover Events, the authors suggested `. . . that the series of recent epidemics sparked by zoonotic spillover are not an aberration or random cluster, but follow a multi-decade trend in which spillover-driven epidemics have become both larger and more frequent.'Which means that even if we are lucky enough that the current HPAI H5N1 threat fizzles, there is almost certainly another pandemic contender in the wings, waiting to begin its world tour.