#18,514

Tomorrow will mark the 5 year anniversary of the first reports of an unidentified pneumonia hospitalizing people in Wuhan, China. A little before midnight on Dec 30th, 2019 the dedicated newshounds at FluTrackers began posting reports of a `SARS-like' illness in Hubei province.Around 2am Sharon Sanders messaged me on Skype, and by 4am I posted the first of 3 blogs (see China: 27 Cases of `Atypical Viral Pneumonia' Reported In Wuhan, Hubei) I'd write on New Year's Eve day on that event (see also here & here).

It would take nearly a week before the WHO and CDC would publicly address the situation in China, and nearly three weeks (Jan 18th) before China would admit to `limited human-to-human transmission' of the virus.

While it is not entirely certain when the first cases began to appear in China (some estimates put it as early as November) - largely due to the slow release of information - the WHO and the US would not declare COVID emergencies until the end of January.

By that time the virus was already spreading rapidly in Europe, and had been repeatedly introduced into the United States. Whatever advantage an early warning might have provided us was squandered during those first few weeks.

Today, the sharing of disease information is arguably even worse.

According to the WHO, only 11% of the world's nations are consistently reporting COVID ICU admissions or deaths. This is a downward trend we've been watching for several years now (see 2023's No News Is . . . Now Commonplace).

As a result, the WHO has been forced to add the following disclaimer to their monthly epidemiology reports:

While officially the COVID pandemic has claimed roughly 7 million lives since 2020, unofficial estimates run 2 or 3 times higher. China alone, is thought to have under-reported millions of deaths.It is important to note that the data presented in this report do not necessarily reflect the actual number of cases and deaths or the actual number of countries where cases and deaths are occurring, as several countries have stopped reporting or changed their frequency of reporting.

Sins of omission (don't count, don't test, don't report) have become commonplace. Even normalized.

Some of this may be due to an actual drop in disease activity, but there are a lot of political and economic incentives not to report cases.

This year we've seen roadblocks in the United States preventing the testing of dairy and beef cattle for HPAI H5, and while that is slowly changing, after 9 months we still don't have a good handle on how widespread the virus really is in American livestock.

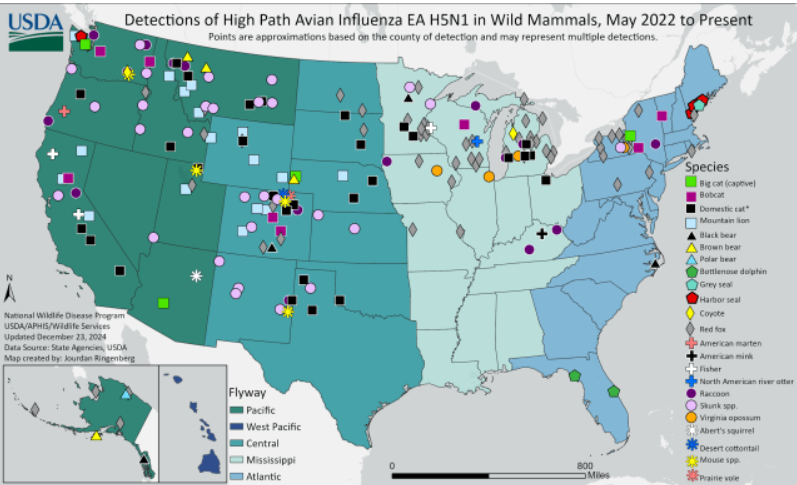

Surveillance and testing of wildlife remains sporadic, with many states yet to report a single instance, while others have reported scores.

And while the government continues to reassure the public about the limited number of confirmed human H5 cases (n=66), the reality is our surveillance systems are poorly equipped to pick up community cases of the virus.

Most in-office or in-clinic testing for influenza can't differentiate between seasonal flu and avian flu. Even hospitalized patients may not be immediately diagnosed (see Missouri H5 Case).

Last summer the ECDC published Enhanced Influenza Surveillance to Detect Avian Influenza Virus Infections in the EU/EEA During the Inter-Seasonal Period which cautioned:

Sentinel surveillance systems are important for the monitoring of respiratory viruses in the EU/EEA, but these systems are not designed and are not sufficiently sensitive to identify a newly emerging virus such as avian influenza in the general population early enough for the purpose of implementing control measures in a timely way.

Similarly, in 2023's analysis from the UKHSA (see TTD (Time to Detect): Revisited), the UK estimated there could be dozens or even hundreds of undetected human H5N1 infections before public health surveillance would likely detect them, potentially over a period of weeks or even months.

Instead, we seem to be less well prepared today than we were a decade ago.

While we may get lucky, and skate through 2025 - or beyond - without seeing another pandemic, at some point our luck will run out (see BMJ Global: Historical Trends Demonstrate a Pattern of Increasingly Frequent & Severe Zoonotic Spillover Events).

And when that happens, we'll truly wish we had the time back we are squandering now, pretending the next pandemic won't happen on our watch.