UK HAIRS Timeline - 20 years of Emerging Viruses

#18,572

A dozen years ago, in in mBio: A Strategy To Estimate The Number Of Undiscovered Viruses, we saw an early attempt to estimate the number of undiscovered mammalian viruses in the world.

Researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health, EcoHealth Alliance, the NIH, et al. came up with `. . . minimum of 320,000 mammalian viruses awaiting discovery.'

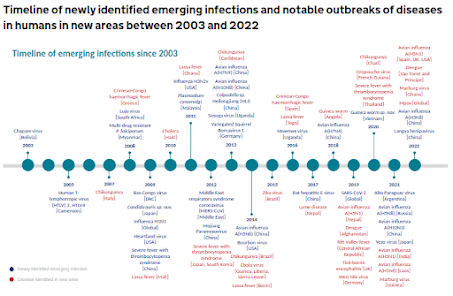

Of course, that is just an estimate. Some researchers put that number well over 1 million. Like it or not, we live in a pathogen-rich environment, and every few months we learn about some new or expanding disease threat in the wild (see HAIRS timeline above).

Most of these viruses will have a narrow host-range, or only be slightly zoonotic. Meaning their impact on public health will be nil. But a significant number will be capable of spilling over into humans and causing varying levels of disease.This initial report indicated - in addition to the confirmed human infections - that genetic testing of 25 animals found low levels of the virus in dogs (5%) and goats (2%), but much higher levels (27%) in shrews, which they suspect may be the reservoir host for this virus.

Last August, in Nature: Decoding the RNA Viromes in Shrew Lungs Along the Eastern Coast of China, researchers described a remarkably diverse range of pathogens (including influenza H5N6) in Shrews captured along the East Coast of China. The authors wrote:

Our analysis revealed numerous shrew-associated viruses comprising 54 known viruses and 72 new viruses that significantly enhance our understanding of mammalian viruses. Notably, 34 identified viruses possess spillover-risk potential and six were human pathogenic viruses: LayV, influenza A virus (H5N6), rotavirus A, rabies virus, avian paramyxovirus 1, and rat hepatitis E virus.

Although many of these studies have been conducted in far-flung places like China, the United States is not without a history of emerging viruses.

- In August of 2012 (see New Phlebovirus Discovered In Missouri) the CDC’s announced a new tick-borne virus had been detected in two Missouri farmers living 60 miles apart. Since then scores of cases across 14 states have been reported.

- Three years later, another virus (see CDC & EID Journal On The Recently Discovered Bourbon Virus) was discovered in Bourbon County, Kansas. To date, 5 cases across 3 states have been reported, although it is likely underreported.

- This marks the first detection of a henipavirus in North America.

- The virus is related to known human-infecting shrewborne henipaviruses (e.g. LayV, GAKV and DARV).

- This species of shrews are widely distributed across central and eastern North America.

Volume 31, Number 2—February 2025

Research Letter

Henipavirus in Northern Short-Tailed Shrew, Alabama, USA

Rhys H. ParryComments to Author , KayLene Y.H. Yamada, Wendy R. Hood, Yang Zhao, Jinlong Y. Lu, Andrei Seluanov, Vera Gorbunova, Naphak Modhiran, Daniel Watterson, and Ariel Isaacs

Abstract

RNA metagenomic analysis of tissues from 4 wild-caught northern short-tailed shrews in Alabama, USA, revealed a novel henipavirus (family Paramyxoviridae). Phylogenetic analysis supported the placement of the virus within the shrew henipavirus clade, related to human-infecting shrewborne henipaviruses. Our study results highlight the presence of henipavirus infections in North America.

Henipaviruses (family Paramyxoviridae) are zoonotic, negative-sense RNA viruses harbored primarily by bats. Henipaviruses can cross species barriers, infecting various mammals, including humans; they often cause severe respiratory illness and encephalitis and are associated with high case fatality rates (1). The 2 most notable henipaviruses are Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Hendra virus, first identified in Australia, has caused outbreaks with mortality rates up to 70% (1). Nipah virus has been linked with numerous outbreaks in Southeast Asia, particularly in Malaysia and Bangladesh, with case-fatality rates estimated at 40%–75% (1), depending on surveillance and clinical management.

In 2018, researchers identified a novel henipavirus, Langya virus (LayV), in patients from China’s Shandong and Henan Provinces (2). A total of 35 persons were infected with LayV, displaying such symptoms as fever, fatigue, and cough and, in some cases, impaired liver or kidney function. No fatalities have been reported thus far. Most investigators believe the primary reservoir host for LayV to be shrews, but the virus has also been detected in goats and dogs, indicating a wide potential host range.

In 2021, researchers conducting a mammalian longevity study captured 4 northern short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda; order: Eulipotyphla, family: Soricidae) in the wild at Camp Hill, Auburn, Alabama, USA (latitude 32.82, longitude −85.65) (3).

(SNIP)

The discovery of a novel henipavirus in B. brevicauda shrews highlights the potential of this shrew species as a zoonotic reservoir, capable of harboring multiple viruses that pose a risk to humans. Of note, the B. brevicauda shrew is a known host of Camp Ripley virus (genus Orthohantavirus) (6,7), a viral genus associated with severe human disease. Camp Ripley virus was abundant in tissues from all the individual shrews analyzed, suggesting mixed co-infections of hantaviruses and henipaviruses in the shrews we studied. In addition, a prior report has implicated B. brevicauda shrews as reservoir for Powassan virus (genus Orthoflavivirus) (8), capable of causing life-threatening encephalitis.

The northern short-tailed shrew is widely distributed across central and eastern North America, from southern Saskatchewan to the Atlantic provinces of Canada and south to northern Arkansas and Georgia in the United States (Appendix Figure 2). Despite their solitary nature, short-tailed shrews are territorial and highly active, commonly found in rural and urban areas near livestock, agricultural settings, and human populations. Although the shrews has large home ranges that sometimes overlap with human activity, they typically inhabit woodland areas with >50% herbaceous cover (9), making direct encounters with humans uncommon.

Given the high case-fatality rates associated with henipaviruses, detection of CHV in North America raises concerns about past and potential future spillover events. Further investigation is needed into the potential for human infection and strategies for mitigating transmission. Our findings help elucidate the prevalence and geographic distribution of CHV in B. brevicauda shrews. The exact transmission mechanisms of shrew henipaviruses remain unclear, but direct contact with infected animals or their excreta poses a risk to humans.

Dr. Parry is a postdoctoral researcher at the School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, Australia. His research topics cover virus bioinformatics and molecular characterization of metagenomics-identified viruses.

Admittedly, the public health impact of this North American Henipavirus may never amount to much, but 15 years ago no one could have predicted that camels would become the host species - and primary spillover threat - of a deadly coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

Until 1999, West Nile Virus was unknown in North America. Now it is endemic, and it infects thousands, and claims scores of lives each year. The CDC estimates that > 475,000 people may be infected with Lyme Disease each year.

And despite many conflicting theories, the origins of Sars-CoV-2 remain murky at best, while a year ago the notion of hundreds of American dairy herds infected with HPAI H5N1 would have been dismissed as highly unlikely.

A reminder that what may seem like a trivial, or incidental finding today, could become a much bigger concern tomorrow.The list goes on.