#18,412

It's been just over a week since the flurry of media reports on the death of a toddler in Andhra Pradesh, India from the H5N1 virus (see Apr 2nd's Media Reports Of Fatal H5N1 Case in Child In Andhra Pradesh, India).

While many of these media reports cite `government sources', over the past week I've not been able to find any confirmation published on an official government website.

The official X/Twitter account for Health, Medical & Family Welfare Department, Government of Andhra Pradesh is quite active, with scores of updates for the month of April, but with no mention of H5N1.

Their webpage (https://hmfw.ap.gov.in/) has links for Notifications and News/Media, but none of them appear to work, and their (COVID centric) Facebook page hasn't been updated since Sept 2022.

Similarly, searches of the Government of India Press Information Bureau (in both English & Hindi) turn up no mention of this case, and only two press releases mentioning H5N1 (here, and here) this month. Several other Indian govt sites were simply unresponsive despite multiple attempts to access them.

Sadly, this game of hide and seek with official data isn't unusual, and it isn't just from India (see From Here To Impunity). Our ability to track individual spillovers and outbreaks continues to deteriorate as more and more countries decide there is little to gain by releasing detailed information.

Yesterday the WHO released their latest SEAR (South-East Asia Region) Epidemiological report, which included a section on H5N1 in India (as of April 5th). I must assume that the WHO has not yet been officially notified of this case, since there is no mention of any human infections.

India: Highly pathogenic avian influenza

Situation as of 5 April 2025

• Between 1 January and 4 April 2025, India has witnessed continued outbreaks of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) across both domestic poultry and non-poultry species.

• According to a press release published by the India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, a total of 34 epicentres have been identified in domestic poultry across eight states—Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka and Bihar. Of these, six epicentres remain active, spanning three states: Jharkhand (Bokaro and Pakur), Telangana (Ranga Reddy, Nalgonda, and Yadadri Bhuvanagiri), and Chhattisgarh (Baikunthpur and Korea).

• Notably, HPAI has also spilled over to non-poultry species, raising concerns. In Maharashtra, infections have been reported in tigers, leopards, vultures, crows, hawks, and egrets. Madhya Pradesh reported a case in a pet cat, while Rajasthan saw infections in demoiselle cranes and painted storks. Bihar and Goa reported cases in crows and a jungle cat, respectively. The involvement of wildlife and domestic pets underscores the potential ecological and zoonotic implications of the outbreak.

• The Department of Animal Husbandry & Dairying (DAHD) has implemented a series of initiatives to control and prevent the spread of HPAI in India. The country follows a strict "detect and culling" policy, which involves culling infected birds, restricting movement, and disinfecting areas within a 1 km radius of outbreaks.

• A three-pronged strategy to prevent and control HPAI outbreaks has been proposed, encompassing stricter biosecurity measures at poultry farms, strengthened surveillance and mandatory registration of poultry farms.

• The situation calls for continued intersectoral coordination and public awareness to mitigate risks.

This WHO summary only captures some of the spillovers reported to WOAH since the first of the year (see partial list below).

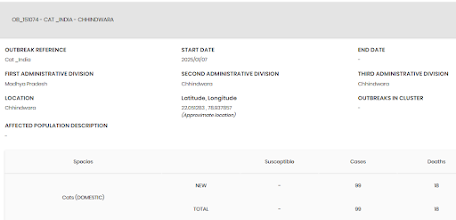

Two days later (Feb 24th) we looked at a preprint on feline infections in Chhindwara with a triple-reassortant H5N1 virus (see Preprint: HPAI A (H5N1) Clade 2.3.2.1a Virus Infection in 2 Domestic Cats, India, 2025).

While I've no doubt we'll eventually get an update on this latest human case from India via the WHO, it is disconcerting how much H5N1 activity there appears to be in India, and how few details we are privy to.

Of course we've heard no updates since the initial announcement of the UK's human H5 infection in January, or on the UK's H5N1 infected Sheep reported more than 2 weeks ago. H5N1 reports have slowed markedly here in the United States since January, and many countries remain completely silent on the threat.

Two weeks ago we looked a scathing report on the delays (months, sometimes even > 1 year) by countries submitting H5N1 sequence data to GISAID (see Nature: Lengthy Delays in H5N1 Genome Submissions to GISAID).

While I have no way to accurately quantify how much we aren't hearing about H5N1, it is a pretty good bet it is substantial. And this silence extends far beyond just H5N1 (see Flying Blind In The Viral Storm).

A reminder that no news doesn't necessarily mean `good news'.