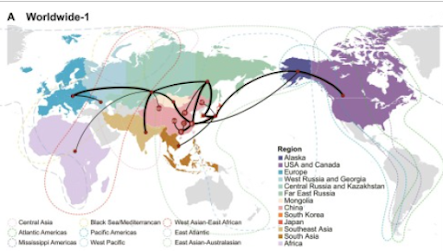

Transmission routes of HA sequences from H3 sublineages at a global scale

#18,769

Avian H3 viruses have sparked human pandemics before; including 1968's H3N2 virus, and a suspected H3N8 pandemic in the early 1900s. More than 57 years after it emerged, H3N2 continues to circulate in humans, and is often the cause of the most severe flu seasons.

While not considered a `reportable' virus in poultry or wild birds, H3Nx viruses have been making considerable inroads into mammalian hosts since the middle of the last century.

- about 60 years ago H3N8 jumped unexpectedly to horses, supplanting the old equine H7N7 and is now the only equine-specific influenza circulating the globe

- in 2004 the equine H3N8 virus mutated enough to jump to canines, and began to spread among greyhounds in Florida (see EID Journal article Influenza A Virus (H3N8) in Dogs with Respiratory Disease, Florida).

- in 2011 avian H3N8 was found in marine mammals (harbor seals), and 2012’s mBio: A Mammalian Adapted H3N8 In Seals, provided evidence that this virus had recently adapted to bind to alpha 2,6 receptor cells, the type found in the human upper respiratory tract.

- in 2015's J.Virol.: Experimental Infectivity Of H3N8 In Swine, we saw a study that found that avian (but not canine or equine) H3N8 could easily infect pigs.

- And in 2022 we saw the first two human infections in China (see Hong Kong CHP Finally Notified Of 2nd H3N8 Case On the Mainland)

A month ago, in Preprint: Fatal infection of a novel canine/human reassortant H3N2 influenza A virus in the zoo-housed golden monkeys, we saw yet another novel H3 subtype (H3N2) jump species in China.

As the map at the top of this blog illustrates, what happens with avian flu in Chinese wild birds and poultry isn't guaranteed to remain in China.

Today we've a lengthy and detailed look at the ecology, evolution, and global spread of H3 subtype avian influenza viruses. I've only posted some excerpts. Those looking for a deeper dive will want to follow the link to read it in it's entirety.

I'll have a bit more after the break.

Jiaying Yang a b 1, Xiaojing Chen a 1, Xiyan Li b, Ye Zhang b , Jia Liu b, Min Tan b c, Hong Bo b, Wenfei Zhu b, Lei Yang b, Dayan Wang b, Yuelong Shu a c

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2025.106542

Under a Creative Commons license

Highlights

• Multiscale transmission hotspots for H3 subtype avian influenza viruses were identified, such as Alaska, Central Asia, and Guangdong/Guangxi provinces in China.

• H3 sublineages evolved faster after introduction from wild birds to domestic poultry.

• Chicken-origin H3N8 G25 viruses exhibited accelerated evolution compared to duck-origin H3 viruses.

Summary

The H3 subtype avian influenza virus (AIV) has been widely spread in birds and known as a natural source of mammalian influenza viruses. Based on data from public databases and our surveillance data, we analysed the ecology, evolution, and spread of H3 AIVs.

Sublineages of H3 AIVs have been detected worldwide, infecting various birds, at least 90 species in wild birds and poultry. Important areas for large-scale and local dissemination of H3 AIVs were identified, such as Alaska, Central Asia, and Chinese provinces.

The H3 viruses have elevated the HA gene substitution rate after introduction from wild birds to domestic poultry, and even faster in domestic chickens. Our results implied an evolutionary mechanism of H3 AIV cross-species transmission, that viruses from wild birds to domestic poultry have accelerated substitution rate by shorter generation time and host selection. Novel chicken H3 viruses, especially H3N8 G25 viruses that have spilled over to humans, require high attention.

(SNIP)

Regional spread of H3 sublineagesTwo sublineages, Asia and EA-North America, had spread intra continentally. The Asia sublineage spanned multiple countries within the eastern Asian continent (Appendix Figure 7). Mongolia might play a key role for virus spatial diffusion. Transmission routes between Mongolia and other Asian regions, including northern China, eastern China, Far East Russia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, were highly supported (Fig. 3A).

EA-North America sublineage viruses were mainly detected in Alaska (Appendix Figure 8). Statistical evidence supports that viral transmission may occur between Alaska and the Canadian Prairies, as well as between the Canadian Prairies and the Western USA. (Fig. 3B).

In this study, we have found several hot spots for H3 AIV large-scale spreading, including Alaska, Central Asia, Japan, Eastern China, and Mongolia.

Alaska is an important pathway for H3 AIV to spread between the Eastern Hemisphere and the Western Hemisphere, e.g., sublineage Worldwide-1 and Europe-Asia. Migratory waterfowls, particularly green-winged teals25 and northern pintails26, that could rapidly fly long distances carrying AIVs were frequently monitored in Alaska, where overlaps of flyways may contribute to the intercontinental movement of AIVs between Eurasia and North America27.

Less than a month later, in (December 2014) we saw H5Nx wing its way from Asia to North America for the first time, dispelling the notion that the Western Hemisphere was somehow protected by vast ocean distances.

We revisited this risk in 2016 in USGS: Alaska Still A Likely Portal For Introduction Of Avian Viruses. There are also Atlantic Ocean overlaps between the European and North American flyways (see PLoS One: North Atlantic Flyways Provide Opportunities For Spread Of Avian Influenza Viruses).

These migratory flyway overlaps helped funnel H5Nx into North America in late 2014, and H5N1 in 2021 (see Multiple Introductions of H5 HPAI Viruses into Canada Via both East Asia-Australasia/Pacific & Atlantic Flyways).

All of which means that what happens with avian flu in the chicken coops of China, or the flyways of Siberia, is more than just a local concern.

And if China's scientists are troubled by what they are seeing with H3Nx, we probably should be paying closer attention.