UK HAIRS Timeline - 20 years of Emerging Viruses

#18,787

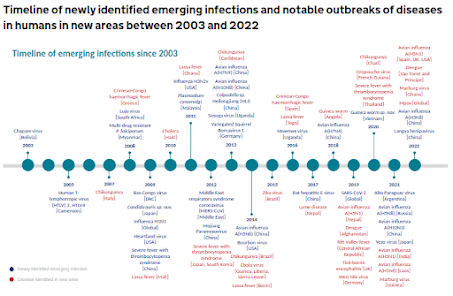

As the above graphic illustrates, we've seen no shortage of emerging infectious disease threats in the first quarter of this 21st decade, a pattern that was forecast in the mid-1990s by renown anthropologist and researcher George Armelagos (May 22, 1936 - May 15, 2014) of Emory University.I first became aware of Dr. Armelagos’ concept after reading Dr. Michael Greger’s book Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching nearly 20 years ago, and first fleshed it out in a 2011 blog (see The Third Epidemiological Transition).

In a nutshell, Armelagos et al. proposed that the history of human disease could be divided into 4 broad eras marked by three major transitions. The first era, dubbed the Paleolithic Baseline, depicts the first few million years of human existence, up to about 10,000 years ago.

The First Epidemiological Transition occurred when humans moved away from being nomadic hunter gatherers towards a more agricultural society, about 100 centuries ago. Humans settled into larger population clusters, which gave pathogens an opportunity to spread more easily.

- The domestication of animals brought other disease vectors in close contact with humans. Q Fever, Anthrax, and tuberculosis all gained access to human hosts.

- The cultivation of soil, and the clearing of land, exposed people to insect bites, bacteria, and parasites.

- As cities grew, and exploration of the surrounding world increased, man spread deadly diseases in ever-greater numbers. Cholera, plague, influenza, and typhus all became major scourges for humanity.

The Second Epidemiological Transition began roughly 200 years ago, with the Industrial revolution.

- With advances in medicine, sanitation, and technology the average lifespan markedly increased. With that came diseases of age that simply hadn’t been all that common when 40 years was considered a long life (e.g. heart problems, osteoarthritis, cancer).

- Technology also brought with it smokestack industries, chemical toxins, working indoors as opposed to out, increased stress, and greater access to less `healthful’ food.

- And, particularly over past 120 years - with the advent of airplanes, ocean crossing ships, automobiles and trains - travel became far faster, and more assessable for the masses.

In a 2010 paper, Armelagos along with Kristin Harper, updated his original work. Both papers are well worth reading.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010 February; 7(2): 675–697.

Published online 2010 February 24. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020675.The Changing Disease-Scape in the Third Epidemiological Transition

Kristin Harper and George Armelagos

Not only have we we seen unprecedented outbreaks of zoonotic diseases (Ebola in West Africa, Zika, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, H5Nx, etc.) over the past 25 years, we've seen forecasts strongly suggesting the frequency, and intensity of these outbreaks are only likely to increase over the next couple of decades.

BMJ Global: Historical Trends Demonstrate a Pattern of Increasingly Frequent & Severe Zoonotic Spillover Events

PNAS Research: Intensity and Frequency of Extreme Novel Epidemics

All of which brings us to an editorial, published yesterday in the Journal Zoonotic Diseases - which looks at the drivers of zoonotic viral spillover; including:

- Ecological and Environmental Drivers

- Climatic Regime Alterations

- Anthropogenic and Socioeconomic Factors

- Microbial Evolution and Viral Adaptation

I've only posted the link, and the abstract. Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a brief postscript when you return.

Drivers of Zoonotic Viral Spillover: Understanding Pathways to the Next Pandemic

by Jonathon D. Gass, Jr.

Zoonotic Dis. 2025, 5(3), 18; https://doi.org/10.3390/zoonoticdis5030018

Submission received: 26 June 2025 / Accepted: 3 July 2025 / Published: 7 July 2025

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid growing concerns regarding viral threats such as avian influenza, Mpox, and HKU5 bat coronaviruses, the phenomenon of viral zoonotic spillover, when viruses leap from circulation in non-human animals to humans, has garnered unprecedented global attention. While such events may appear spontaneous, they are deeply intertwined with ecological, environmental, and social processes that are reshaping the boundaries between the domains of animal and human populations.

As we move deeper into the Anthropocene, namely the current geological epoch defined by human dominance over Earth’s ecosystems, the frequency and impact of viral zoonotic spillovers that lead to localized, regional, and global disease outbreaks are expected to rise.

Understanding the current and future drivers of zoonotic viral spillover thus requires pro-active and integrated global One Health action. In this Editorial, I examine the key ecological, environmental, and socio-behavioral drivers of viral zoonotic spillover, highlight high-risk pathogens with pandemic potential, and provide a call-to-action by outlining several evidence-based strategies to reduce viral zoonotic spillover in the future.

The authors states: `Viral zoonotic spillover is not an anomaly—it is a foreseeable consequence of unsustainable human activities' and offers a number of important Strategies for a Safer Future.

Sadly, we find ourselves in a society that too often prioritizes profits over public health, and that frequently opts for short-term fixes when dealing with long-term problems.

A reminder that however many (real or imagined) victories we may declare against emerging infectious diseases, nature has nearly unlimited resources, a surfeit of time, and the advantage of always batting last.