# 6688

RIDTs, or Rapid Influenza Detection Tests, are popular in-office test kits that are designed to detect Influenza A and Influenza B infections in 15 minutes or so.

They are quick, convenient and reasonably inexpensive - but their accuracy has come under scrutiny n the past (see No Doesn’t Always Mean No).

The two main measures of the accuracy of a diagnostic test are sensitivity and specificity.

- Sensitivity is defined as the ability of a test to correctly identify individuals who have a given disease or condition.

- Specificity is defined as the ability of a test to exclude someone from having a disease or illness.

The CDC, on their Rapid Diagnostic Testing for Influenza webpage, cautions:

Reliability and Interpretation of Rapid Test Results

-

The reliability of rapid diagnostic tests depends largely on the conditions under which they are used. Understanding some basic considerations can minimize being misled by false-positive or false-negative results.

- Sensitivities of rapid diagnostic tests are approximately 50-70% when compared with viral culture or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and specificities of rapid diagnostic tests for influenza are approximately 90-95%.

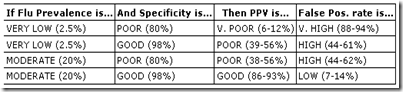

- False-positive (and true-negative) results are more likely to occur when disease prevalence in the community is low, which is generally at the beginning and end of the influenza seasons.

- False-negative (and true-positive) results are more likely to occur when disease prevalence is high in the community, which is typically at the height of the influenza season.

Which means that while a positive result carries a pretty high confidence level, a negative result is considered less reliable.

Today’s MMWR carries an evaluation of 11 commercial Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests that were available during the 2011-2012 season. They were tested against 23 flu viruses (16 A & 6 B strains) that have circulated in the United States since 2006.

Each virus was tested at five different dilution strengths, in order to gauge relative sensitivity of these tests. All but one managed to correctly return a positive result at the highest tested viral concentration, but at lower titers the results were highly variable.

It’s a lengthy report, and you’ll probably want to follow the link to read more about the methods, and results. A few excerpts follow, after which I’ll have a little more.

Evaluation of 11 Commercially Available Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests — United States, 2011–2012

Weekly

November 2, 2012 / 61(43);873-876Accurate diagnosis of influenza is critical for clinical management, infection control, and public health actions to minimize the burden of disease. Commercially available rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) that detect the influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP) antigen are widely used in clinical practice for diagnosing influenza because they are simple to use and provide results within 15 minutes; however, there has not been a recent comprehensive analytical evaluation of available RIDTs using a standard method with a panel of representative seasonal influenza viruses.

This report describes an evaluation of 11 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–cleared RIDTs using 23 recently circulating influenza viruses under identical conditions in a laboratory setting to assess analytical performance.

Most RIDTs detected viral antigens in samples with the highest influenza virus concentrations, but detection varied by virus type and subtype at lower concentrations.

Clinicians should be aware of the variability of RIDTs when interpreting negative results and should collect test samples using methods that can maximize the concentration of virus antigen in the sample, such as collecting adequate specimens using appropriate methods in the first 24–72 hours after illness onset. The study design described in this report can be used to evaluate the performance of RIDTs available in the United States now and in the future.

At this point, you may be wondering how doctors are supposed to interpret results from a test that may, or may not, correctly show when a patient has the flu.

It gets pretty complicated, but the CDC provides guidance on not only how to interpret the results, but also under what circumstances they recommend using these diagnostic kits at:

Guidance for Clinicians on the Use of Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests

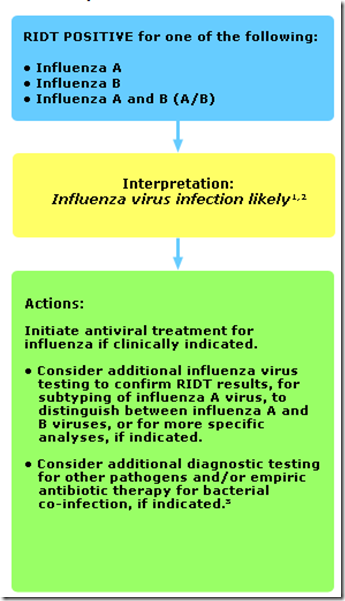

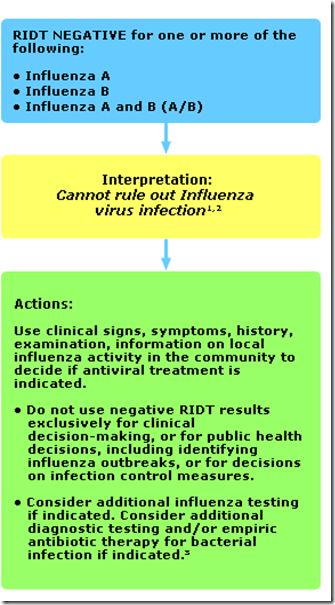

You’ll find several decision tree charts on this page, including the following two which are used to interpret RIDT results during periods when influenza viruses are circulating in the community.

In part 1, the RIDT returns a positive result.

In Part 2, the RIDT returns a Negative result.

While these test kits can provide help with diagnostic and treatment decisions for individual patients in clinical settings, they are probably more valuable when used to identify influenza outbreaks in institutions, like hospitals, schools, or nursing homes.

Even if each individual result can’t be fully trusted, a few positive results out of a confined population displaying influenza-like symptoms can help guide decisions regarding prevention and control.

Of course, better rapid tests are obviously needed. Not just for common seasonal strains, but ideally for all flu strains.

But until they become available, doctors must carefully weigh RIDT results along with the patient’s clinical signs and symptoms - and level of flu in the community - in order to come up with the best diagnosis.