Cloth Masks used during the 1918 Pandemic

# 9973

Over the years we’ve looked repeatedly at the relative protectiveness of PPEs - personal protective equipment (N95s, PAPRs, disposable med/surgical masks) - but due to their rare usage in the developed world, have only infrequently addressed the use of washable cloth or cotton masks, whose use remains ubiquitous in developing countries.

- Almost a decade ago the CDC’s Journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases offered plans for making a simple homemade reusable mask made out of Tee-shirt material (see The Man In The Ironed Mask).

- Another study, which appeared in PLoS One in 2008 (see What Everyone Will Be Wearing During The Next Pandemic Flu Season), found that homemade masks – while not as effective as N95s – could offer some degree of protection against viral infection.

- And last year, in MERS: Are Two Surgical Masks Better Than One?, we looked at a report in the International Journal of Infection Control called Use of cloth masks in the practice of infection control – evidence and policy gaps by Chughtai, Seale & MacIntyre that found a lack of evidence on the efficacy of cloth masks.

Cloth facemasks went the way of the Dodo bird in U.S. healthcare settings decades ago, replaced by inexpensive disposable surgical masks. Cloth masks are still used by many HCWs – particularly in low resources settings - around the world and would likely be embraced by the public during a pandemic.

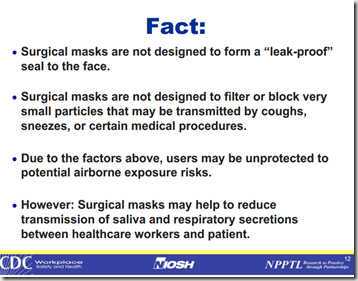

While the level of protection they provide to the wearer has been long debated (see NIOSH Webinar: Debunking N95 Myths & The Great Mask Debate Revisited), given their low cost and the fact that they don’t have to be individually `fitted’, disposable surgical masks are routinely worn by HCWs.

In the developing world, however, disposable PPEs are a luxury that few hospitals can afford. Reusable cloth masks and gowns are frequently employed, even when dealing with highly infectious diseases like measles, novel influenza, or hemorrhagic fevers.

In the event of a localized epidemic (or worse, a pandemic), disposable PPEs will be quickly be in very short supply.

At one time the HHS estimated the nation would need an impossible 30 billion masks (27 billion surgical, 5 Billion N95) to deal with a major pandemic (see Time Magazine A New Pandemic Fear: A Shortage of Surgical Masks).

So the question becomes, just how protective are cloth (reusable) face masks?

According to a study, published yesterday by the BMJ Open Journal, is `not very’. In fact, there is some evidence they may actually increase infection risks.

First a link to the study (again by Chughtai, Seale & MacIntyre, et al.), and some excerpts from the abstract and the UNSW press release.

BMJ Open 2015;5:e006577 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577

A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers

C Raina MacIntyre1, Holly Seale1, Tham Chi Dung2, Nguyen Tran Hien2, Phan Thi Nga2, Abrar Ahmad Chughtai1, Bayzidur Rahman1, Dominic E Dwyer3, Quanyi Wang4

Published 22 April 2015

Abstract

Objective The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of cloth masks to medical masks in hospital healthcare workers (HCWs). The null hypothesis is that there is no difference between medical masks and cloth masks.

Setting 14 secondary-level/tertiary-level hospitals in Hanoi, Vietnam.

Participants 1607 hospital HCWs aged ≥18 years working full-time in selected high-risk wards.

Intervention Hospital wards were randomised to: medical masks, cloth masks or a control group (usual practice, which included mask wearing). Participants used the mask on every shift for 4 consecutive weeks.

Main outcome measure Clinical respiratory illness (CRI), influenza-like illness (ILI) and laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection.

Results The rates of all infection outcomes were highest in the cloth mask arm, with the rate of ILI statistically significantly higher in the cloth mask arm (relative risk (RR)=13.00, 95% CI 1.69 to 100.07) compared with the medical mask arm. Cloth masks also had significantly higher rates of ILI compared with the control arm. An analysis by mask use showed ILI (RR=6.64, 95% CI 1.45 to 28.65) and laboratory-confirmed virus (RR=1.72, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.94) were significantly higher in the cloth masks group compared with the medical masks group. Penetration of cloth masks by particles was almost 97% and medical masks 44%.

Conclusions This study is the first RCT of cloth masks, and the results caution against the use of cloth masks. This is an important finding to inform occupational health and safety. Moisture retention, reuse of cloth masks and poor filtration may result in increased risk of infection. Further research is needed to inform the widespread use of cloth masks globally. However, as a precautionary measure, cloth masks should not be recommended for HCWs, particularly in high-risk situations, and guidelines need to be updated.

Public Release: 22-Apr-2015

Cloth masks -- dangerous to your health?

University of New South Wales

The widespread use of cloth masks by healthcare workers may actually put them at increased risk of respiratory illness and viral infections and their global use should be discouraged, according to a UNSW study.

The results of the first randomised clinical trial (RCT) to study the efficacy of cloth masks were published today in the journal BMJ Open.

The trial saw 1607 hospital healthcare workers across 14 hospitals in the Vietnamese capital, Hanoi, split into three groups: those wearing medical masks, those wearing cloth masks and a control group based on usual practice, which included mask wearing.

Workers used the mask on every shift for four consecutive weeks.

The study found respiratory infection was much higher among healthcare workers wearing cloth masks.

The penetration of cloth masks by particles was almost 97% compared to medical masks with 44%.

Professor Raina MacIntyre, lead study author and head of UNSW's School of Public Health and Community Medicine, said the results of the study caution against the use of cloth masks.

The recommendation by MacIntyre et al. is that Health care workers not rely on reusable cloth masks, as their use is associated with an increased risk of infection. The authors list a number of limitations to this study, however, and it isn’t at all clear whether wearing cloth masks was detrimental to HCWs.

They only showed that the lowest rates of infection were in the medical mask group, while the highest rates were seen in those wearing the cloth masks.

And it must be stated that not all cloth masks are created equal (nor are all disposable surgical masks) in terms of quality, fit, and filtration. Additionally, the question as to whether cloth masks have a legitimate role for the public during an epidemic – as a protection of last resort – is not addressed in this study.

In 2006, the IOM published a report entitled Reusability of Facemasks During an Influenza Pandemic: Facing the Flu, which addressed the issue of `improvised’ masks during a pandemic, and while not exactly endorsing them, accepts the will likely be necessary.

Regulatory standards require that a medical mask should not permit blood or other potentially infectious fluids to pass through to or reach the wearer’s skin, mouth, or other mucous membranes under normal conditions of use and for the duration of use. It is not clear that cloth masks or improvised masks (e.g., towels, sheets) can meet these standards.

Without better testing and more research, cloth masks or improvised masks can not be recommended as effective respiratory protective devices or as devices that would prevent exposure to splashes.

However, these masks and improvised devices may be the only option available for some individuals during a pandemic. Given the lack of data about the effectiveness of these devices in blocking influenza transmission, the committee hesitates to discourage their use but cautions that they are not likely to be as protective as medical masks or respirators. The committee is concerned that their use may give users a false sense of protection that will encourage risk-taking and/or decrease attention to other hygiene measures.

Given that supplies of disposable masks in this interpandemic period are plentiful, and their cost is minimal (< .10 each), it isn’t such a bad idea to put back a few boxes of surgical masks in your family’s emergency stockpile, rather than being forced to rely on homemade improvised masks.

But all stockpiles are finite, and if I were down to only having cloth masks at my disposal, I would still bank on the idea that wearing any mask beats wearing none at all.