# 6173

Over the past two days we’ve seen two highly divergent papers come out on the probable spread, and Case Fatality Rate, of the H5N1 virus in the human population.

The lead author of the first one was Peter Palese and the second Michael Osterholm. Both are scientists of considerable reputation in the world of infectious diseases.

You can access them via my blogs below:

Science: Peter Palese On The CFR of H5N1

mBio: Mammalian-Transmissible H5N1 Influenza: Facts and Perspective

In 25 words or less, though:

Professor Palese maintains that seroprevalence studies suggest `millions’ of uncounted H5N1 infections, and would indicate the virus is nowhere near as deadly as has been proclaimed.

Osterholm cites flaws in some of those studies, and using WHO guidelines for testing, finds scant evidence to support the idea that many cases go uncounted, and the CFR is low.

Shamefully simplistic summaries on my part, but we’ve covered this territory many times in the past few days. I would encourage everyone to read both papers in their entirety.

In the wake of their publication, we are starting to see some media coverage and comparison of the two papers, and reactions from other scientists on this issue.

First stop, Reuters, which has a long report on this controversy, which was published before the mBio paper was released this morning.

Bird flu may not be so deadly after all, new analysis claims

NEW YORK | Fri Feb 24, 2012 6:38am EST

Despite the title, this report does quote the World Health Organization as standing behind their numbers, and has comments by Arturo Casadevall and Michael Osterholm disputing Palese’s results.

Next, New Scientist has a report by Debora MacKenzie that looks at the debate, and along the way she posits a theory of her own.

New doubt over H5N1 death rate – but risks still high

16:50 24 February 2012

And lastly, Lisa Schnirring of CIDRAP News has undertaken a difficult task and (skillfully, I think) has put together a comparison of the two papers.

She includes reactions from several leading scientists (including Gaun Yi and Marc Lipsitch) who have read the papers.

Debate on H5N1 death rate and missed cases continues

Lisa Schnirring

Staff Writer

Feb 24, 2012 (CIDRAP News) – Two leading voices on the potential threat of lab-modified H5N1 viruses laid out their arguments about the human H5N1 fatality rate and undetected cases today and yesterday, with one group claiming "millions" likely have been infected and the other group saying current World Health Organization (WHO) fatality-rate estimates are about right.

While this is a fascinating debate, and I know just about everyone would like to know the true CFR of the H5N1 virus (myself included), I’m not sure how much value (or comfort) that we would derive if we had that knowledge.

First, we tend to talk about the H5N1 virus as if it were a single, monolithic virus.

It isn’t.

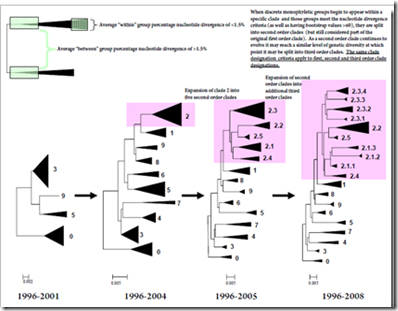

There are more than 20 identified clades (and growing), with many minor variations within each clade.

If we could figure out the CFR for the clades commonly found in Indonesia (2.1.1, 2.1.2. and 2.1.3), it probably wouldn’t tell us much about those circulating in Egypt (2.2.1 and 2.2).

And it might tell us even less about the CFR of some future human-adapted H5N1 virus that may one day appear.

As any prospectus will warn you, Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

So even if we were accept that Professor Palese is correct, and the CFR of currently circulating H5N1 strains are somewhat less than 1%, I’m not exactly comforted by that knowledge.

I think what is important here is that this virus has been shown to provoke severe, often devastating illness in nearly all of the humans cases we’ve confirmed so far. It also seems to have a preference for younger victims.

Admittedly, that could change as the virus evolves.

But it is enough to convince me that we need to regard this virus as a dangerous and formidable pathogen, regardless of whether its CFR right now turns out to be 30% or .3% or somewhere in between.

Because if a new and improved version of the virus ever emerges, all of the old arguments (and datasets) will quickly become academic.