# 6547

Timing is, as they say, everything.

And coming on the heels the announcement 10 days ago of three human infections with a swine-origin H1N2 influenza (see Minnesota Reports Swine H1N2v Flu), a study that appears today in PNAS is certainly well timed.

The study, conducted at Chungbuk National University South Korea examined viruses circulating in Korean swine (H1N2 & H3N2), and found - for the most part - they were not particularly pathogenic in ferrets.

The exception was a triple reassortant H1N2 virus dubbed Sw/1204, that had picked up two notable mutations, and it not only transmitted efficiently, it also caused severe (even fatal) disease in the test animals.

The study, is called:

Virulence and transmissibility of H1N2 influenza virus in ferrets imply the continuing threat of triple-reassortant swine viruses

Philippe Noriel Q. Pascua, Min-Suk Song, Jun Han Lee, Yun Hee Baek, Hyeok-il Kwon, Su-Jin Park, Eun Hye Choi, Gyo-Jin Lim, Ok-Jun Lee, Si-Wook Kim, Chul-Joong Kim, Moon Hee Sung, Myung Hee Kim, Sun-Woo Yoon, Elena A. Govorkova, Richard J. Webby, Robert G. Webster, and Young-Ki Choi

Ed Yong, writing for Nature has the details on this paper:

Need for flu surveillance reiterated

Study of Korean pigs finds virus with pandemic potential.

Ed Yong 10 September 2012

One to the two mutations discussed in this paper is hemagglutinin (HA) (Asp-225-Gly) – also known as D225G – which is something we’ve looked at a number of times in the past.

This mutation involves a single amino acid change in the HA gene at position 225 (H3 numbering) from aspartic acid (D) or Asp to glycine (G), and was first linked to more severe pandemic flu by Norwegian Scientists in 2009.

The evidence for the D222G/N amino acid substitution driving increased virulence, and deep lung infection, has been mixed, however. A few earlier blogs include:

Eurosurveillance: Debating The D222G/N Mutation In H1N1

Study: Receptor Binding Changes With H1N1 D222G Mutation

WER Review: D222G Mutation In H1N1

The second mutation, called NA-315 (serine to asparagine the in neuraminidase) isn’t as well studied, but is believed to assist the virus in breaking out of infected cells after replicating.

As Ed Yong mentions in his article - viruses often have multiple amino acid changes – and we are really just beginning to understand the ramifications of these different genetic combinations.

Whether this particular virus ever ends up posing a public health threat is impossible to say, but it does illustrate these swine reassortant viruses aren’t always mild in mammals.

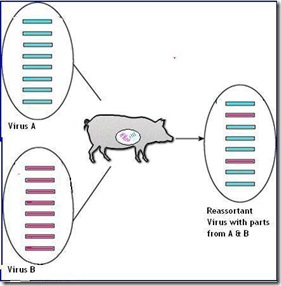

New strains of influenza come about from reassortment; the swapping of genetic material between two different flu strains in a common host. We tend to focus on swine, simply because they are highly susceptible to a variety of influenza viruses, and have a history of producing reassorted viruses.

The pandemic virus that emerged in the spring of 2009 was the end product of several influenza strains that had kicked around the world’s swine population for many years, trading bits of genetic material back and forth, until they produced a version capable of jumping to humans.

But any host (human, swine, avian, or other mammal) could produce a reassorted virus.

For more on the flu risks from swine reassortments, I continue to heartily recommend Helen Branswell’s terrific piece in SciAm from late 2010 called Flu Factories.

Flu Factories

The next pandemic virus may be circulating on U.S. pig farms, but health officials are struggling to see past the front gate

By Helen Branswell | December 27, 2010 |

And for some of my earlier looks at swine influenza, you may wish to revisit: