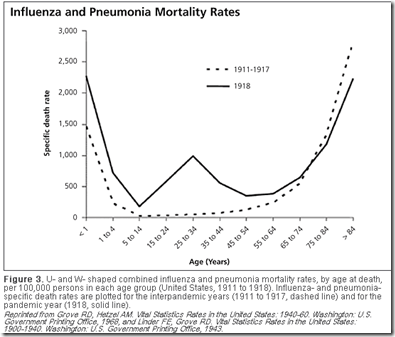

The infamous `W shaped curve’ of the 1918 pandemic clearly shows that the death rates among those in their teens, 20s, and 30s was much higher than was normally seen in previous influenza years. Those over the age of 65, however, saw a reduction in mortality during the pandemic.

# 6778

Seasonal influenza can strike people of any age, but exacts its greatest toll on the elderly – those over the age of 65 – whose weaker immune systems (and comorbid conditions) often render them less able to fight off the infection.

Exact numbers remain elusive, since influenza is only rarely cited as the primary cause of death. If a cause of death (beyond`natural causes’) is given, comorbidities like COPD, heart disease, asthma are far more likely to listed on a death certificate.

Still, estimates are that 90% of seasonal flu mortality occurs in those over the age of 65 (cite CDC Pink book).

In 2010, (see Study: Years Of Life Lost Due To 2009 Pandemic), researchers estimated the median age of death due to seasonal influenza-related illness in the United States to be 76.

In contrast, pandemic influenza strains, at least during the first few years after their introduction, often produce a dramatic `age shift’ downward in mortality.

The CDC’s estimate of average and median age of death due to the 2009 Pandemic virus reads:

Based on two CDC investigations of confirmed 2009 H1N1-related deaths that occurred during the spring and fall of 2009, the average age of people in the U.S. who died from 2009 H1N1 from April to July of 2009 was 40. The median age of death for this time period was 43. From September to October of 2009, the average age of people in the U.S. who died from 2009 H1N1 was 41, and the median age was 45.

Admittedly, younger fatalities are more likely to be investigated, and documented, than those that occur among the elderly, but still . . . this is a significant shift.

And it corresponds closely to the results of the Years Of Life Lost Study mentioned above, which found the mean age of death from the novel H1N1 virus to be half that of seasonal flu, or 37.4 years.

In terms of years of life lost (YLL), the average pandemic flu death has a many fold greater impact than the average seasonal flu fatality.

This same pattern was repeated (to greater and lesser degrees) during the 1918, 1957, and 1968 pandemics . . . along with the 1977 return of the H1N1 virus after an absence of 20 years.

All of which has led to a good deal of speculation.

What drives this age shift? Why were apparently healthy, younger flu victims, with robust immune systems more likely to die from pandemic flu?

Although not universally accepted, one popular theory has centered around the production of a `cytokine storm’, which is believed to be the product of a robust immune system typically found in younger, healthier individuals.

Cytokines are a category of signaling molecules that are used extensively in cellular communication. They are often released by immune cells that have encountered a pathogen, and are designed to alert and activate other immune cells to join in the fight against the invading pathogen.

This cascade of immune cells rushing to the site of infection, that if it races out of control, can literally kill the patient.

The patient’s lungs can fill with fluid (which makes a terrific medium for a bacterial co-infection), and cells in the lungs (Type 1 & Type II Pneumocytes) can sustain severe damage.

You can find more on this theory in these earlier posts:

Study: Calming The Cytokine Storm

Cytokine Storm Warnings

The Baskin Influenza Pathogenesis Study

Another theory has held that older populations are more likely to have been exposed to a similar influenza strain in the past and are more likely to carry some level of immunity to the emerging pandemic strain.

This was clearly the case in 1977, when the H1N1 virus – supplanted by the H2N2 virus in 1957 – made an unexpected comeback. Those born after the virus last circulated in the mid 1950s – were the hardest hit age group.

Again with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus, those born before the early 1950s appeared to have higher levels of immunity, resulting in fewer severe outcomes among older individuals.

All of which serves as prelude to a research article, published yesterday in BMC Medicine, that looks at the age shift during pandemic outbreaks.

The age distribution of mortality due to influenza: pandemic and peri-pandemic

Tom Reichert, Gerardo Chowell and Jonathan A McCullers

Background

Pandemic influenza is said to 'shift mortality' to younger age groups; but also to spare a subpopulation of the elderly population. Does one of these effects dominate? Might this have important ramifications?

Methods

We estimated age-specific excess mortality rates for all-years for which data were available in the 20th century for Australia, Canada, France, Japan, the UK, and the USA for people older than 44 years of age. We modeled variation with age, and standardized estimates to allow direct comparison across age groups and countries. Attack rate data for four pandemics were assembled.

Results

For nearly all seasons, an exponential model characterized mortality data extremely well; For seasons of emergence and a variable number of seasons following, however, a subpopulation above a threshold age invariably enjoyed reduced mortality. 'Immune escape', a stepwise increase in mortality among the oldest elderly, was observed a number of seasons after both the A(H2N2) and A(H3N2) pandemics. The number of seasons from emergence to escape varied by country. For the latter pandemic, mortality rates in four countries increased for younger age groups but only in the season following that of emergence. Adaptation to both emergent viruses was apparent as a progressive decrease in mortality rates, which, with two exceptions, was seen only in younger age groups. Pandemic attack rate variation with age was estimated to be similar across four pandemics with very different mortality impact.

Conclusions

In all influenza pandemics of the 20th century, emergent viruses resembled those that had circulated previously within the lifespan of then-living people. Such individuals were relatively immune to the emergent strain, but this immunity waned with mutation of the emergent virus. An immune subpopulation complicates and may invalidate vaccine trials. Pandemic influenza does not 'shift' mortality to younger age groups; rather, the mortality level is reset by the virulence of the emerging virus and is moderated by immunity of past experience. In this study, we found that after immune escape, older age groups showed no further mortality reduction, despite their being the principal target of conventional influenza vaccines. Vaccines incorporating variants of pandemic viruses seem to provide little benefit to those previously immune. If attack rates truly are similar across pandemics, it must be the case that immunity to the pandemic virus does not prevent infection, but only mitigates the consequences.

The complete article is available as a provisional PDF.

The entire article is worthy of your attention, and the authors delve into a good many areas, including future pandemic mitigation planning, and vaccine strategies.

But essentially the authors propose that all recent influenza pandemics (over the past century) have involved `recycled’ flu strains to which some portion of the population had previously been exposed to.

They conclude:

Pandemics do not ‘shift’ mortality to younger agesFrom this study, it is evident that pandemics do not ‘shift’ mortality to younger ages. Rather, the

entire mortality level is simply reset to the virulence level of the emergent virus. This reset is accompanied by immunoprotection in older age groups, which is determined by their level of previous experience with viruses similar to that emerging.

In other words, were older populations not carrying some vestiges of immunity from previously flu encounters, these researchers suggest they would suffer the same levels (or higher) of mortality and morbidity as do younger populations.

The authors also point out that initial levels of immunity to emerging (or more properly, re-emerging) influenza viruses in older populations tends to wane in subsequent seasons, leading to what they call Immune Escape: `a stepwise increase in mortality among the oldest elderly’.

Does this blow the whole cytokine storm theory out of the water?

Not necessarily, although it does call into question just how much of an impact it has on the perceived `age shift’ in pandemic flu cases.

These two theories need not be mutually exclusive, however, and so I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that both may play a part in driving pandemic mortality demographics.