Photo Credit – CDC

# 6843

Over the past two years Hong Kong has experienced a dramatic increase in the number of Scarlet Fever cases, while at the same time, cases in Mainland China have been reportedly surged as well.

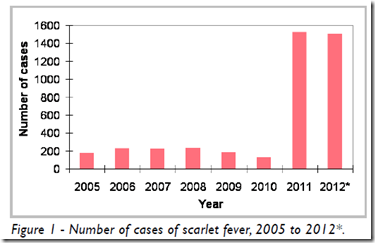

The chart below illustrates Hong Kong’s 7-to-9 fold increase over 2005-2010.

Credit Hong Kong CHP

Scarlet fever is caused by the same bacteria that causes `strep throat’ (Group A Streptococcus), and is characterized by fever, a very sore throat, a whitish coating or sometimes `strawberry’ tongue, and a `scarlet rash’ that first appears on the neck and chest.

It primarily affects children under the age of 10. Adults generally develop immunity as they grow older. Untreated, this bacterial infection can lead to:

- Rheumatic fever

- Kidney disease

- Ear infections

- Skin infections

- Abscesses of the throat

- Pneumonia

- Sepsis

- Arthritis

For more on the disease, here is the CDC’s Scarlet Fever: A Group A Streptococcal Infection information page.

In the summer of 2011, we saw reports that many of these recent Hong Kong infections were resistant to erythromycin, but still responded to Penicillin.

The CHP also reported:

A new genome fragment was discovered by the Department of Microbiology of the University of Hong Kong (HKU) upon sequencingthe whole genome of a GAS isolate from a child suffering from SF and invasive GAS infection admitted to QMH.

Subsequent testing by the PHLSB on other GAS isolates found that 70-80% of emm type 12 strains and 50-60% of emm type 1 strains carried this new genomefragment. The contribution of new GAS clone(s) with altered genetic characteristics (such as the new genome fragment) causing the current upsurge of SF remains to be investigated.

Today, Hong Kong’s Centre For Health Protection released their latest Communicable Disease Watch, which includes a detailed epidemiological look the past year’s Scarlet Fever activity.

Scarlet fever – local epidemiology and severe cases in 2012

Reported by Miss Amy Li, Scientific Officer, Respiratory Disease Office, Surveillance and Epidemiology Branch, CHP.

Scarlet fever (SF) is a bacterial infection caused by Group A Streptococcus (GAS) and is a statutorily notifiable disease in Hong Kong. The main symptoms are fever, sore throat and erythematous rash with sand-paper texture. The tongue may have a distinctive "strawberry"-like (red and bumpy) appearance. SF can be treated by antibiotics effectively. Although the illness is usually mild, severe cases can occur and complications may include middle ear infection, throat abscess, pneumonia, sepsis, shock, septicaemia, meningitis, and toxic shock syndrome.This article reviews the local epidemiology and severe cases of SF in 2012.From 2006 to 2010, the annual number of SF cases ranged between 128 and 235. In 2011, there was an upsurge in SF cases resulting in an annual total of 1526 cases. During the same period of time, there was a simultaneous increase of SF cases in Mainland China and Macao, suggesting the rise of SF cases in Hong Kong was likely a regional phenomenon.

The related details were reported in June and July 2011 (http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/cdw_v8_13.pdf and http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/cdw_v8_14.pdf). In 2012, the number of SF cases reported to CHP reached 1508* cases which was comparable to that of 2011 (Figure 1). In Hong Kong, relatively more cases occur from December to May though this seasonal pattern was not consistently observed every year (Figure 2). The local activity of SF has been high recently, with cases gradually increased from 65 in October to 132 in November and 119 in December 2012*.

(SNIP)

In view of the high activity of SF recently, people who are suspected to have SF should consult their doctor promptly. Patients who are suffering from SF should not go to schools or child care centres until they fully recover.To prevent SF,people should:

- Maintain good personal and environmental hygiene;

- Keep hands clean and wash hands properly;

- Wash hands when they are dirtied by respiratory secretions, e.g., after sneezing;

- Cover nose and mouth while sneezing or coughing and dispose of nasal and mouth discharge properly; and

- Maintain good ventilation.

As we saw in 2011, this report states that :`60 percent of GAS isolated in 2012 were resistant to erythromycin (which also predicts resistance to azithromycin and clarithromycin).’

While Penicillin and first generation cephalosporins are still effective, this is another example of a serious bacterial infection - once easily treated – evolving to evade our antibiotic arsenal.

The list of resistant bacteria continues to expand, with names like MRSA, NDM-1, KPC, EHEC, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and now Scarlet Fever making headlines around the world.

So while the end of the antibiotic era is not yet at hand, many experts fear we may be drawing closer to that day (see World Faces A `Post-Antibiotic Era’).

Short of seeing a hugely virulent pandemic – the problem of growing antimicrobial resistance may be the greatest threat to global public health that our species faces over the next couple of decades.