# 2386

There was a period of time, of nearly 30 years duration, where infectious diseases almost seemed conquered here in the United States and in much of the developed world.

That golden age ran from around 1955 to the mid 1980s.

With the advent of the Salk Vaccine in 1955, we finally had the tool with which to eradicate the last great childhood scourge in this country; Polio. By 1963, an early measles vaccine had been developed, and in the late 1970s significant improvements had been made in the existing mumps vaccine.

Antibiotics could cure just about any bacterial infection, although very rarely a resistant infection would appear. Early antivirals were developed in the late 1950's, although they saw limited use during the 1960's and 1970's.

It seemed that, for whatever ails you, there was a pill or a shot that would cure it. The only exception being the common cold. And, we were assured, they were working on that.

In 1969, the Surgeon General of the United States, William H. Stewart, declared, "The war against diseases has been won."

It was in this age that I grew up, and worked as a paramedic.

Sure, heart disease and strokes took a heavy toll. As did cancer and severe trauma.

But many trauma victims were now surviving because we were getting them early treatment - during the fabled `golden hour' - utilizing lessons learned during the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Trained paramedics with MAST anti-shock trousers, IV fluids in the field, and even rapid evac with helicopters to trauma centers were making a difference. It was an exciting time to be in emergency medicine.

Up until around 1985, it felt as if we were winning the battle.

But over the past 20+ years, emerging infectious diseases have returned with a vengeance.

You might be wondering exactly where do these new `emerging' diseases emerge from? Where were they last week, or last year? Are they really new?

As Dr. Greger points out in his book and video, Bird Flu: A virus of our own hatching, most of these diseases are zoonotics: diseases that can infect, and pass between, animals and humans.

Many of these diseases have been brought into the human population by the domestication of certain animals. Colds come, originally, from horses. Influenzas from aquatic birds like ducks. Measles, Whooping Cough, Typhoid, Tuberculosis . . . all of them are believed to have a barnyard origin.

As man encroaches deeper into rainforests, swamps, and jungles he is also more likely to encounter seldom seen pathogens.

The practice of consuming bushmeat in Africa, sadly mostly primates, has been linked to the transmission of the HIV virus to man, and is likely behind many of the Ebola outbreaks we've seen.

Over the past 30 years, we've seen more than 30 new (or at least previously unrecognized) emerging infectious diseases. Diseases like Nipah, Hendra, Hanta . . .

While it is too soon to know, it is possible that the South African outbreak last week stemmed from a previously unknown arenavirus. In Uganda last December, a new strain of Ebola was reportedly detected.

Sometimes an existing virus or bacteria. . .something we've seen before . . .will change. It will mutate, and in so doing, become more virulent.

This is one of the reasons why low pathogenic bird flu viruses are reportable diseases, and why flocks are culled when they are encountered. Low pathogenic viruses can mutate into highly pathogenic viruses.

Another influenza pandemic, caused by a novel avian flu virus, is the greatest worry. Followed, I suppose, by the possibility of Virus X, something new, unknown, and highly transmissible. It happened with AIDS, and it could certainly happen again.

But it is difficult for the average resident of a developed nation to imagine being affected by either of those scenarios. Of course, that perception could change overnight if a new pathogen emerges.

Until then, here are three emerging (or re-emerging) infectious diseases that, short of a pandemic, could very well affect you . . . or someone you know.

Proving it doesn't take a pandemic to ruin your whole day.

Lyme disease, or borreliosis, is a particularly nasty, and hard to treat bacteria that is carried by a variety of ticks that can now be found in just about every state in the nation, and increasingly, around the world.

There are 37 known species of borrelia, and 12 of them are known to produce disease symptoms in humans.

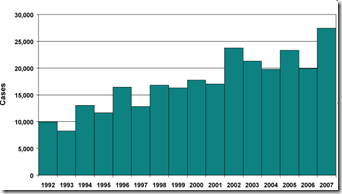

Ticks are major vectors of disease both here in the United States and around the world. The number of Lyme cases reported to the CDC has increased steadily over the past 15 years, but these numbers probably do not reflect the real number of those infected.

Reported Cases of Lyme Disease by Year, United States, 1992-2007

In 2007, 27,444 cases of Lyme disease were reported yielding a national average of 9.1 cases per 100,000 persons. In the ten states where Lyme disease is most common, the average was 34.7 cases per 100,000 persons.

As a Lymie, and one who was initially misdiagnosed back in the 1990s - and therefore didn't get the right treatment - I can assure you this is one nasty little bug you don't want to get.

The danger from ticks isn't limited to Lyme Disease. Ticks can also carry and transmit Babesiosis , Ehrlichiosis, Bartonella, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI), and in eastern Europe, Africa, and parts of Asia Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. There are also a number of other Rickettsial Infections that can be acquired from ticks.

MRSA, or Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is an increasingly common antibiotic resistant bacteria. Once only rarely found in a hospital, or long-term care setting, MRSA has now exploded in prevalence and can now be found outside of these settings, and in the community at large.

The CDC published a study in the October, 2007 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association that said:

Invasive MRSA Infections in the United States

They found a standardized incidence rate of 31.8 per 100 000 persons and estimate that 94 360 infections occurred in 2005, of which 18 650 were potentially fatal. Most infections were health care associated, but 58% occurred outside of the hospital, caused by strains commonly attributed to both community and health care sources.

MRSA is now being connected to pediatric flu deaths around the country. While the numbers are still small, the trend is ominous.

The overuse of antibiotics, particularly in the agricultural sector, is viewed as the prime driver of creating antibiotic resistant bacteria. The quantity of antibiotics consumed each year by humans pales in comparison to what is administered to farm animals.

While I occasionally dabble in the MRSA story, the real expert blogger on the real expert on the net is Maryn McKenna, whose blog Superbug is highly recommended.

C. Difficile, like MRSA, is generally considered a nosocomial infection - or one that is acquired in a hospital or care facility - although it too is being seen in outpatients now. It is listed by the NIH as a re-emerging infectious disease.

C. difficile infections may be asymptomatic, or may be the source of significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in the elderly or the immunocompromised.

While primarily thought of as a side effect to receiving antibiotic therapy - C. Dif is quite easily acquired simply by being in a hospital setting.

This from an article entitled Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea by Michael S. Schroeder M.D, which appeared in the March 2005 edition of the AAFP journal.

Acquisition of C. difficile occurs primarily in the hospital setting, where the organism has been cultured from bed rails, floors, windowsills, and toilets, as well as the hands of hospital workers who provide care for patients with C. difficile infection

The organism can persist in hospital rooms for up to 40 days after infected patients have been discharged.

The rate of C. difficile acquisition is estimated to be 13 percent in patients with hospital stays of up to two weeks and 50 percent in those with hospital stays longer than four weeks.

Patients who share a room with a C. difficile-positive patient acquire the organism after an estimated hospital stay of 3.2 days, compared with a hospital stay of 18.9 days for other patients.

You can add West Nile Virus to the list. And Chikungunya is making inroads, and may soon be a problem for Europe and the United States. Dengue is marching through the South Pacific, Asia, and the Caribbean. And we are watching Adenovirus 14 and Enterovirus 71 with interest.

And these are just the more common ones. I've left out the obscure ones.

No . . . none of these are capable of sparking a pandemic. But all are capable of prompting regional outbreaks, and causing much illness and even death.

If, after reading this, you are beginning to feel just a little surrounded, as if you lived in a world rife with pathogens . . . well, you'd be right.

The primary reason why we've managed to keep most of these diseases at bay these past 50 years has been due to the hard work of public health agencies.

While they don't often get much credit, they are largely responsible for the successes we've had in controlling these outbreaks.

Frankly, the only time we tend to hear about them, or even think about them, is when they have failed to prevent an outbreak.

Public health is usually the last to get funded, and the first to see budget cuts. We follow this remarkably foolish pattern year after year - yet we expect the CDC, the WHO, and local health departments around the world to protect us from disaster.

At one time, arguably, the greatest threat to mankind was the cold war. Trillions were spent over several decades, on both sides, to keep it from turning hot. That threat, thankfully, has cooled down.

Today, the greatest threat to our society is microbial.

And to fight that enemy, we need a different kind of army, with different weapons. And so while our attention is focused temporarily on solving economic problems, we can't afford to ignore public health.

Because, make no mistake, this is a war we can't afford to lose.