# 2641

As a lad growing up in the 1950's and 1960's in Florida, I believed that our future held wondrous and exciting adventures for all mankind. That anything was possible.

Small wonder, since this is the future we were promised.

I grew up close enough to Cape Canaveral, that I could see the huge Atlas rockets lift off as they headed to outer space. I expected that we'd have colonies on the moon, and Mars by the year 2000.

I eagerly awaited every opportunity to go to the used book store downtown where I could purchase back copies of Popular Science and Popular Electronics, for a nickel apiece.

My heroes were the Mercury 7 astronauts, and I wanted to become a scientist, like Dr. Frank Baxter from those slightly wacky, but wonderful Bell Telephone Science films.

When I was 10, I helped my über-geek brother-in-law build a Tesla Coil so powerful, it could only be run after midnight, because it blocked all TV reception for a mile around it.

You could stand 10 feet away, holding a florescent tube, and it would light up in your hand. Get too close, and it would zap you.

Yes, I was a science geek. Before it was even popular.

I fully expected to grow up to have a flying car in my plastic-bubble garage which I would use to commute to my 3-day-a-week job in a shiny new metropolis.

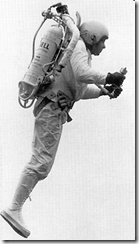

When I was six years old, Bell Labs demonstrated the first `rocket belt', which would allow a man to fly.

I sure wanted one of those, too.

And I really thought I would have one, too. It was just a matter of time.

Fast forward nearly 50 years, and most of the promises that those wonderful magazines of my youth made have failed to come true.

So you'll understand why, when I read about some medical advance that is `10 years away', that will eventually cure the common cold, or eliminate influenza, or prevent my underwear from leaving red marks around my waist . . . I'm a little bit skeptical.

Luckily, not everyone is as cynical as I am.

First this latest article on some very interesting research, then a bit more blather on my part.

British scientists develop nasal spray that could stop the flu virus from laying you low

By Fiona Macrae

Last updated at 11:08 PM on 08th January 2009

A simple spray could help prevent the flu virus from spreading

A spray that might stop flu in its tracks is being developed by scientists.

It would fight off all strains of the virus, including those behind bird flu and winter flu.

Researchers at St Andrews University are developing a nasal spray that would stop people from being infected when the bug is circulating.

Flu kills up to 22,000 Britons a year.

A pandemic of the human form of bird flu - which many believe is inevitable - could claim 700,000 lives in the UK alone.

The current flu jab protects only three-quarters of those vaccinated and needs to be reformulated each year to keep on top of changes in the virus's appearance.

Anti-flu drugs that attack the bug are available. But they are mainly used to treat the infection and the virus can mutate to become resistant to treatment.

The one-size-fits-all spray works in a different way.

Instead of attacking the bug directly, it latches on to the cells it infects, stopping the virus from taking hold.

Usually, the flu virus enters the cells of our nose, throat and lungs by locking on to a sugar sticking out from their surface.

Once inside, the virus rapidly multiplies, before bursting its way out, killing the cells in the process.

Scientists at St Andrews have created a range of proteins that bind to the sugar, stopping the flu bug in its tracks.

Targeting the sugar rather than the virus itself means the bug is unlikely to become resistant to the drug, say the researchers.

And as all strains of flu use the same sugar - sialic acid - when infecting cells, the protein-based drug should ward off all types of the disease.

Following promising initial lab tests, the researchers have received funding to move on to animal tests.

If these prove successful, the technology could be sold to a drugs firm and a nasal spray could be on the market in less than ten years.

We've covered RBD's, or receptor binding domains, in this blog before. For some deep background you can read Looking For the Sweet Spot, and a follow-up blog called Receptor Binding Domains:Take Two.

RBDs are areas of a virus that allows it to attach to receptor cells in a host's body. Different viruses are attracted to different types of cells, which explains why some viruses that affect man, don't affect other species, or vice versa.

Receptor cells have strands of sugar (carbohydrate) molecules on their surface. These carbohydrate molecules - called glycans' - form a dense sugary coating to all animal cell membranes.

When a virus meets a compatible receptor cell, they bind. And infection can ensue.

If you could block these receptor cells, by having something else (hopefully benign) already binding to them, you could theoretically prevent infection.

Farfetched? Perhaps.

But an idea worth pursuing.

I'm a great believer in the idea that research is rarely wasted. That even if this particular idea doesn't work, it may lead to something that will.

So,I can admire the science and the effort behind the research. But I'm not going to pin my hopes on it.

Not again.

Not until I get my rocket belt.

* * * * * * *

If you fondly remember Dr. Frank Baxter (as I do), take heart.

Three of those Bell Telephone Science films are available on the Internet archive to watch online, or to download and inflict on the next generation.

Our Mr. Sun - Frank Capra Productions

Popular scientific film directed by Frank Capra that launched the Bell System Science series. Combining animation and live action, Our Mr. Sun uses a scientist-writer team to present information about the sun and its importance to humankind.

Alphabet Conspiracy - Frank Capra Productions

Part of the Bell Science series. The story of the science of language and linguistics centered around plot to destroy the alphabet and all language. Features Dr. Frank Baxter and the brilliant Hans Conried.

Gateways to the Mind

The story of what science has learned about the human senses and how they function. Includes documentary sequences.