# 5445

Due to its high mortality rate, H5N1 gets most of the world’s attention when it comes to bird flu. While human infections remain rare, among those diagnosed, roughly 60% succumb to the virus.

But H5 isn’t the only avian flu strain we worry about.

There are other – less deadly strains – including the H7s, H9s and H11s that have demonstrated the potential to jump to humans.

Currently, H5s and H7s are both reportable diseases in poultry, due to their ability to mutate from a low pathogenic virus to highly pathogenic virus.

Today, we’ve news of an outbreak of bird flu on a poultry farm near Kapelle, in the Netherlands. The virus has been identified as H7, but the exact subtype has not yet been established.

First a translation of the statement from the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation, after which I’ll return with more.

Bird flu in Zeeland

News item | 03/25/2011

In Zeeland Schore, Chapel congregation is a poultry farm with 127,500 laying hens found bird flu. The H7 is a variant.

Because a low pathogenic H7 variant can mutate into highly pathogenic (highly contagious and lethal for chickens variant), the company both a low and a highly pathogenic variant in accordance with European regulations are removed. The new Food Safety Authority to carry out culling on March 25. In the afternoon of March 25 is known whether a low or a highly pathogenic variant,.

As of March 25, 2011, is 8.00 hours in an area of one kilometer around the company a ban on transporting poultry, eggs, poultry and poultry manure and litter.

The infection probably comes from wild birds excrete the virus in their faeces.

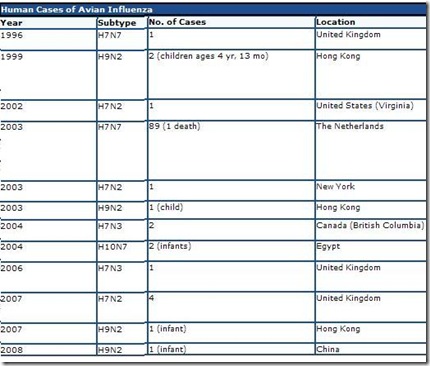

Below you’ll find a chart lifted and edited from CIDRAP’s excellent overview Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): Implications for Human Disease showing non-H5N1 avian flu infections in humans over the past decade.

Perhaps the most notorious outbreak of H7 in humans occurred in 2003 in the Netherlands. It produced (mostly mild) symptoms in at least 89 people, but did cause 1 fatality.

CIDRAP describes it this way:

During an outbreak of H7N7 avian influenza in poultry, infection spread to poultry workers and their families in the area (see References: Fouchier 2004, Koopmans 2004, Stegeman 2004). Most patients had conjunctivitis, and several complained of influenza-like illness. The death occurred in a 57-year-old veterinarian. Subsequent serologic testing demonstrated that additional case-patients had asymptomatic infection.

In 2006 and 2007 there were a small number of human infections in Great Britain caused by H7N3 (n=1) and H7N2 (n=4), again producing mild symptoms.

Since surveillance is – at best - haphazard (or even non-existent) in many parts of the world, how often this really happens is unknown.

For now, H7 avian influenzas pose only a minor public health threat.

Since the H7 viruses generally produce mild symptoms in humans, you may be wondering why all the fuss over an outbreak of H7?

The H7s, like all influenza viruses, are constantly mutating and evolving.

While considered mild today, there are no guarantees that the virus won’t pick up virulence over time, or reassort with another `humanized’ virus and spark a pandemic.

Three years ago, we saw a study in PNAS that indicated that the H7 virus might be moving more towards adapting to humans.

You can read more about this in a couple of blogs from 2008, H7's Coming Out Party and H7 Study Available Online At PNAS.

For more on pandemic threats beyond H5N1 you may wish to revisit:

It Isn’t Just Swine Flu