# 5857

The spring of 2011 saw three record-breaking and deadly tornadic outbreaks across the United States.

First, over three days in mid-April (14th-16th), a severe storm system produced 179 confirmed tornadoes across 16 southern states, resulting in 43 fatalities and more than a half billion dollars in damage.

Two weeks later (Apr. 25th-28th), an even larger outbreak – now dubbed the 2011 Super Outbreak - spawned at least 336 tornadoes across 21 states. More than 300 people died, with the largest number of deaths (249) occurring in Alabama.

Damage estimates for this outbreak exceeded 10 billion dollars.

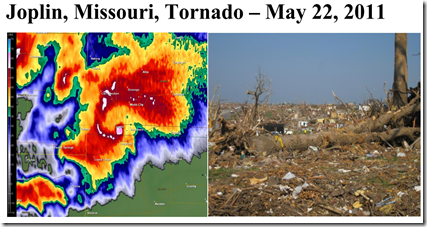

After a remarkably quiet first three weeks of May, another severe storm system swept across the Midwest spawning at least 180 tornadoes over 5 days (May 21st-26th).

The worst of these was the massive F-5 tornado that struck Joplin, Missouri on May 22nd, killing 159 and injuring more than 1,000.

Photo Credit – NOAA

Given the scale of destruction in Joplin, it is a wonder that more people weren’t killed. Fortunately, the city had at least a 20 minute warning via emergency sirens, NWS warnings, and local broadcasters.

Since this was a `warned event’ - yet yielded a high number of fatalities - the National Weather Service launched an investigation over the summer. More than 100 interviews were conducted in Joplin with tornado survivors, local business owners, EMS personnel, the media, and city officials.

Among their findings, many of Joplin’s residents did not act immediately when the tornado sirens sounded. An excerpt from the executive summary explains:

The vast majority of Joplin residents did not immediately take protective action upon receiving a first indication of risk (usually via the local siren system), regardless of the source of the warning. Most chose to further assess their risk by waiting for, actively seeking, and filtering additional information.

The reasons for doing so were quite varied, but largely depended on an individual‘s ― worldview, formed mostly by previous experience with severe weather.

Most importantly, the perceived frequency of siren activation in Joplin led the majority of survey participants to become desensitized or complacent to this method of warning. This suggests that initial siren activations in Joplin (and severe weather warnings in general) have lost a degree of credibility for most residents – one of the most valued characteristics for successful risk communication.

Instead, the majority of Joplin residents did not take protective action until processing additional credible confirmation of the threat and its magnitude from a non-routine, extraordinary risk trigger. This was generally achieved in different ways, including physical observation of the tornado, seeing or hearing confirmation, and urgency of the threat on radio or television, and/or hearing a second, non-routine siren alert.

Having lived in Tornado Alley for a decade, I’m well acquainted with tornado warning fatigue. Sirens go off with some frequency, and severe weather boxes appear in the corner of your local TV broadcast, but often nothing comes of it.

Nationally, the NWS says that 76% of all tornado warnings end up being false alarms. And even if a tornado is spawned, warnings go out across a broad area when only a small number of people are ultimately impacted.

The result is . . . people stop responding to every alert.

Again from the report:

This report suggests that in order to improve warning response and mitigate user complacency, the NWS should explore evolving the warning system to better support effective decision making.

This evolution should utilize a simple, impact-based, tiered information structure that promotes warning credibility and empowers individuals to quickly make appropriate decisions in the face of adverse conditions. Such a system should:

a. provide a non-routine warning mechanism that prompts people to take immediate life-saving

action in extreme events like strong and violent tornadoes

b. be impact-based more than phenomenon-based for clarity on risk assessment

c. be compatible with NWS technological, scientific, and operational capabilities

d. be compatible with external local warning systems and emerging mobile communications

technology

e. be easily understood and calibrated by the public to facilitate decision making

f. maintain existing ―probability of detection‖ for severe weather events

g. diminish the perception of false alarms and their impacts on credibility

A tall order.

And one that is complicated by the sheer volume of `threat warnings’ we get on a daily basis. Everything from weather alerts, to elevated terrorism levels, to warnings that almost everything you eat, drink, or touch is either contaminated or will give you cancer.

After awhile, these warnings tend to fuzz out, blend in, and lose their impact.

While it is tempting to suggest scaling back these warnings, there are 7 scientists on trial in Italy right now – charged with manslaughter - over their failure to predict, and warn the public about an earthquake in 2009.

Charges levied, even though we don’t currently have the technology to accurately predict earthquakes .

Despite the daily clutter of warnings we receive – many of which never materialize - a failure of agencies to warn about known or suspected threats would not be well tolerated by the public.

For the NWS, the challenge will be to create an easily identifiable `immediate threat’ warning to elevate it above the `background noise’ of more generic or broad-based warnings.

As to the myriad other threats out there, they are all the more reason to incorporate an `all threats’ preparedness plan, instead of focusing on one type of scenario.

If you are well prepared for an earthquake, you are also well equipped to handle a hurricane, a pandemic, or any other type of disaster.

In order to promote this idea, FEMA, Ready.gov, and other agencies are promoting September as National Preparedness Month. Follow this year’s campaign on Twitter by searching for the #NPM11 hash tag.