Photo Credit – FAO

UPDATE: The OIE REPORT filed for this incident now identifies this as an H5N2 (not H7 as previously reported) avian influenza strain. (Link)

# 6336

Although this news broke yesterday, I was away from my desk most of the day, and was unable to blog it. Early reports had suggested an H5 strain, but the most recent reporting (via Reuters) is that a low pathogenic H7 avian influenza virus is the culprit.

My thanks to the reader who forwarded this Reuters story to me. I’ll return with a little background on the H7 avian viruses.

Dutch cull 42,700 turkeys after bird flu found

Reuters

12:06 p.m. CDT, March 19, 2012

AMSTERDAM (Reuters) - Dutch authorities said 42,700 turkeys have been culled at a farm in the south of the country after a mild variant of the H7 bird flu strain was reported over the weekend.

While we pay greatest attention to the H5N1 virus due to its observed high mortality in the roughly 600 human cases we’ve identified, there are other – less deadly -avian influenza strains that have been known to infect humans.

Currently, H5s and H7s are both reportable diseases in poultry, due to their ability to mutate from a low pathogenic virus to highly pathogenic virus.

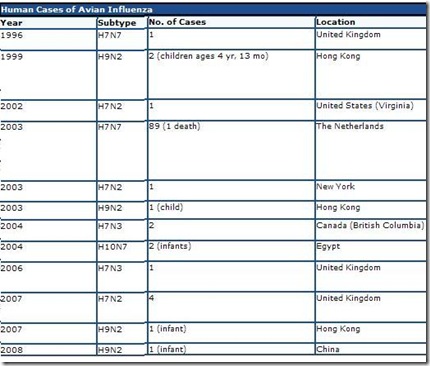

Below you’ll find a chart lifted and edited from CIDRAP’s excellent overview Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): Implications for Human Disease showing non-H5N1 avian flu infections in humans over the past decade.

Perhaps the most notorious outbreak of H7 in humans occurred in 2003 in the Netherlands. It produced (mostly mild) symptoms in at least 89 people, but did cause 1 fatality.

CIDRAP describes it this way:

During an outbreak of H7N7 avian influenza in poultry, infection spread to poultry workers and their families in the area (see References: Fouchier 2004, Koopmans 2004, Stegeman 2004). Most patients had conjunctivitis, and several complained of influenza-like illness. The death occurred in a 57-year-old veterinarian. Subsequent serologic testing demonstrated that additional case-patients had asymptomatic infection.

In 2006 and 2007 there were a small number of human infections in Great Britain caused by H7N3 (n=1) and H7N2 (n=4), again producing mild symptoms.

Since surveillance is – at best - haphazard (or even non-existent) in many parts of the world, how often this really happens is unknown.

For now, H7 avian influenzas pose only a minor public health threat.

Since the H7 viruses generally produce mild symptoms in humans, you may be wondering why all the fuss over an outbreak of H7?

First, eradicating the virus can be time consuming, and horrendously expensive. In 2003 outbreak in the Netherlands mentioned above required the culling of 30 million birds.

And second, the H7s, like all influenza viruses, are constantly mutating and evolving.

While considered mild today, there are no guarantees that the virus won’t pick up virulence over time, or reassort with another `humanized’ virus and spark a pandemic.

In fact, four years ago we saw a PNAS article that suggested that some `humanization’ of the virus was occurring.

As we all know, the last pandemic came out of left field; from a region of the world (North America), host species (swine), and influenza strain (H1N1) considered unlikely to spark a global epidemic.

Which is why even relatively benign avian strains are regarded as potential threats, and dealt with swiftly.