The undisputed ruler of my house

# 6605

When we think of zoonotic transmission of diseases – we usually think of a pathogen from moving from animals to humans – but in truth, diseases can go in both directions.

Luckily, most viruses are fairly selective about the type of cells they will invade, what organ systems they will attack, and even what species they will infect.

This explains why a virus might affect a dog, or a cat, or a bird, yet not affect humans. This species selectivity is known as a `host range'.

Most viruses generally have a fairly narrow host range (there are exceptions, of course. Like rabies). But one of the surprises that came out of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic was that virus’s ability to infect wide range of species.

In December of 2009 in a blog called USDA Listing Of Animals With H1N1 we looked at some early reports of pandemic H1N1 infecting a variety of animals. Along with swine the USDA listed ferrets (5), cats(3), turkeys (5), and a Cheetah (1) as having contracted the virus.

(Click to load PDF file)

The infection of swine with an H1N1 swine-like virus wasn’t unexpected, nor was the susceptibility of ferrets a big surprise. Ferrets are often used in influenza research because they are susceptible to the virus.

The jumping to cats was less expected, given that the only other flu virus known to affect cats was the H5N1 bird flu. Dogs were not immune (see US: Dog Tests Positive For H1N1), either.

In October of 2010 we looked at a study in the EID Journal: Pandemic H1N1 Infection In Cats that found that - while producing less severe symptoms - cats infected with the 2009 H1N1 virus showed similar pathogenic processes to cats infected with the HPAI H5N1 bird flu virus.

While it may not happen very often - with flu season upon us - the potential exists for humans pass one of the seasonal flu viruses on to their pets (or to farm animals).

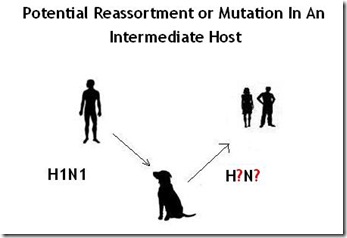

Apart from obvious concern over our pet’s wellbeing, the other worry is the possibility that an influenza’s promiscuous behavior could lead to the creation of a mutated or reassorted strain of the virus.

It is probably more likely that reassortment would occur in swine, birds, or humans – but other species (like dogs, cats, ferrets, skunks, etc.) cannot be ruled out.

All of which brings us to a press release today from the University of Oregon, which talks about the need to study `reverse zoonotic’ influenza infections in pets. I’ve only included excerpts, follow the link to read:

Onset of flu season raises concerns about human-to-pet transmission

10-3-12

CORVALLIS, Ore. – As flu season approaches, people who get sick may not realize they can pass the flu not only to other humans, but possibly to other animals, including pets such as cats, dogs and ferrets.

This concept, called “reverse zoonosis,” is still poorly understood but has raised concern among some scientists and veterinarians, who want to raise awareness and prevent further flu transmission to pets. About 80-100 million households in the United States have a cat or dog.

It’s well known that new strains of influenza can evolve from animal populations such as pigs and birds and ultimately move into human populations, including the most recent influenza pandemic strain, H1N1. It’s less appreciated, experts say, that humans appear to have passed the H1N1 flu to cats and other animals, some of which have died of respiratory illness.

There are only a handful of known cases of this phenomenon and the public health implications of reverse zoonosis of flu remain to be determined. But as a concern for veterinarians, it has raised troubling questions and so far, few answers.

<SNIP>

The researchers are surveying flu transmission to household cat and dog populations, and suggest that people with influenza-like illness distance themselves from their pets. If a pet experiences respiratory disease or other illness following household exposure to someone with the influenza-like illness, the scientists encourage them to take the pet to a veterinarian for testing and treatment.

<SNIP>

The primary concern in “reverse zoonosis,” as in evolving flu viruses in more traditional hosts such as birds and swine, is that in any new movement of a virus from one species to another, the virus might mutate into a more virulent, harmful or easily transmissible form.

“All viruses can mutate, but the influenza virus raises special concern because it can change whole segments of its viral sequence fairly easily,” Loehr said. “In terms of hosts and mutations, who’s to say that the cat couldn’t be the new pig? We’d just like to know more about this.”

Veterinarians who encounter possible cases of this phenomenon can obtain more information from Loehr or Jessie Trujillo at Iowa State University. They are doing ongoing research to predict, prevent or curtail emergent events.

This press release also makes mention of the laboratory interspecies transmission of a canine H3N2 (avian-origin) influenza virus in Korea. You’ll find my coverage of that story at the link below:

Interspecies Transmission Of Canine H3N2 In The Laboratory