H7N9 Age Curve - Credit CIDRAP

# 7194

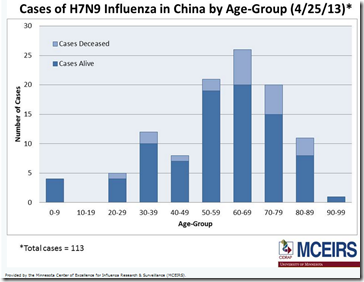

One of the ongoing mysteries surrounding the H7N9 outbreak in China is the disproportionate skewing of known cases towards elderly males – even though all ages in the community are assumed to be equally immunologically naive to this emerging virus.

This excellent chart by Laidback Al clearly shows the disproportionate impact H7N9 is having on the elderly, while the largest segment of the Chinese population – middle-aged adults - are far less represented in the case counts.

Source FluTrackers Demographic and Geographic Overview of H7N9

For some additional discussion on this unusual patterning of cases, you may wish to revisit H7N9: The Riddle Of The Ages and last Monday’s WHO H7N9 Study: Preliminary Age & Sex Distribution.

While many epidemiologists are investigating exposure differences to poultry or other birds that might explain this age/sex shift, researchers from Canada are exploring a different scenario.

One that harkens back to a mystery still unresolved from the 2009 pandemic – the observation (particularly in Canada) that people who received the 2008 flu shot seemed to be more susceptible to catching the H1N1 pandemic strain the following spring.

The so-called `Canadian Problem’.

Fair warning, this letter from the Eurosurveillance Journal offers up a hypothesis based on an extremely complex and poorly understood phenomenon.

None of what follows is exactly `light’ reading.

Rather than mangle the author’s words by excerpting portions here, I would invite you to follow the link and read it in its entirety.

After you return, I’ll take a stab at trying to make it easier to understand (wish me luck).

Eurosurveillance, Volume 18, Issue 17, 25 April 2013

Letters

D M Skowronski, N Z Janjua, T L Kwindt, G De Serres

What follows is a layman’s explanation of some poorly understood areas of our immune system. Real scientists may want to avert their eyes.

Normally, after you’ve been infected by most viruses, you develop neutralizing antibodies that can recognize that pathogen and protect you from being infected again. Variances in individual immune systems and time since exposure can weaken these defenses.

But this is the reason why influenza viruses must continually mutate, else they’d run out of susceptible hosts.

But sometimes, the system doesn’t work as designed.

Sometimes - and for reasons that aren’t well understood - an earlier viral infection can set the host up for a more serious infection when exposed at a later date to a similar virus.

The classic example is with Dengue (DENV), which comes in four flavors (serotypes) – and which typically produces a mild illness with the first infection, regardless of which serotype is acquired.

The problem usually comes later, when a person is infected with a different serotype.

They often (but not always) experience a more severe illness, which can even progress into DHF (Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever).

The prevailing theory is that the host’s immune system - which already has neutralizing antibodies to the first DENV infection - mistakenly identifies the second DENV infection as being the same strain.

Rather than creating new neutralizing antibodies to fight the infection, it deploys its existing cross reactive, but non-neutralizing (read: ineffective) antibodies to the field of battle.

Sometimes called OAS or Original Antigenic Sin, this is the immunological equivalent of taking a knife to a gun fight.

Original Antigenic Sin was coined in 1960 by Thomas Francis, Jr. in the article On the Doctrine of Original Antigenic Sin) that postulates that when the body’s immune system is exposed to and develops an immunological memory to one virus, it may be less able to mount a defense against a subsequent exposure to a second slightly different version of the virus.

OAS has been described in relation to influenza viruses, Dengue Fever, and HIV. You can find a terrific background piece on OAS from 2009 by Robert Roos in my blog entitled CIDRAP On Original Antigenic Sin.

And if mistakenly sending the wrong antibodies into the fray isn’t bad enough, sometimes non-neutralizing antibodies can actually enhance a virus’s ability to enter a host’s cells via a process called ADE or Antibody-dependent enhancement.

The result can be either an increased susceptibility to infection, a more severe course of illness, or both.

In this paper, the authors are suggesting that researchers look beyond simple socio-cultural behaviors to explain the age shift with H7N9, and consider what potential immunological effects that decades of exposures to a variety of influenza viruses might be having on an older population.

It is, as they say, complicated. And not without controversy.

For more on this fascinating, but unresolved `Canadian problem’ - which the authors suggest may have some bearing on the epidemiology of H7N9 - you may wish to revisit:

ICAAC: Ferreting Out The `Canadian Problem’

EID Journal: Revisiting The `Canadian Problem’