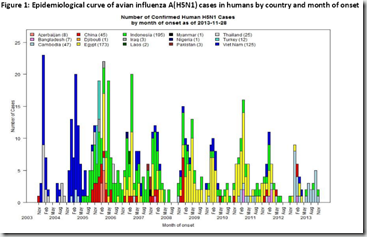

Seasonality of H5N1 – Credit WHO

# 8081

With winter setting in the northern hemisphere, and two novel avian flu viruses (H5N1 & H7N9) in circulation, it is a pretty good bet that we will be hearing about increased outbreaks in poultry, and scattered human infections, over the coming months.

If fact, it would be a big surprise if we didn’t see more cases over the next 5 or 6 months. As the chart at the top of this blog indicates, avian influenza cases historically go up during the winter and spring.

Whether any of these outbreaks will lead to a larger public health concern, remains to be seen. But right now, neither of these viruses has demonstrated the ability to spread efficiently from human-to-human. That could change over time, of course, which is why we watch these cases carefully for any signs the virus is better adapting to human physiology.

The World Health Organization has released their monthly Influenza at the human - animal interface report, dated December 10th, 2013, which reviews the avian flu activity over the previous month, and looks ahead to what we might see over the winter.

Influenza at the human-animal interface

Summary and assessment as of 10 December 2013Human infection with avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses

From 2003 through 10 December 2013, 648 laboratory-confirmed human cases with avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection have been officially reported to WHO from 15 countries. Of these cases, 384 died.Since the last WHO Influenza at the Human Animal Interface update on 7 October 2013, seven new laboratory-confirmed human cases of influenza A(H5N1) virus infection were reported to WHO from Cambodia (6) and Indonesia (1).

In Cambodia, the reported incidence of human cases has increased in 2013 (26 cases in 2013 compared with 21 cases from 2005 through December 2012). This might be due to improvements in surveillance and physician awareness or to a potential increased circulation of the virus in poultry. The case fatality rate among reported cases, however, has decreased (54% in 2013 compared with 90% over all previous years).

Before 2013, H5N1 viruses from clade 1.1 predominated in Cambodia. Analysis of isolates from human cases and birds from the beginning of 2013 revealed the emergence of a new H5N1 genotype resulting from the reassortment of clade 1.1 and clade 2.3.2.1 viruses.

The link between the emergence of this reassortant virus and the increase in human cases observed in 2013 is yet to be determined.

All seven human cases reported in this summary are considered to be sporadic, with no evidence of community-level transmission. As influenza A(H5N1) virus is thought to be circulating widely in poultry in Cambodia and Indonesia, additional sporadic human cases or small clusters might be expected in these countries in the future.

Overall public health risk assessment for avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses: Whenever influenza viruses are circulating in poultry, sporadic infections or small clusters of human cases are possible, especially in people exposed to infected household poultry or contaminated environments. However, this influenza A(H5N1) virus does not currently appear to transmit easily among people. As such, the risk of community-level spread of this virus remains low.

Human infection with other non-seasonal influenza viruses

Avian influenza A(H7N9) in China

Since the last update of 7 October 2013, China has reported six new cases of human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, from Zhejiang (5) and Guangdong (1) provinces, with onset dates between 8 October and 29 November. In addition, the Centre for Health Protection, China, Hong Kong SAR has reported two human cases, one with an onset date of 21 November 2013 and the other with onset at the beginning of December. Both cases had been in Guangdong province in China in the week before clinical onset. Most patients presented with pneumonia.

Most human A(H7N9) cases have reported contact with poultry or live bird markets. Knowledge about the main virus reservoirs and the extent and distribution of the virus in animals remains limited and, because this virus causes only subclinical infections in poultry, it is possible that the virus continues to circulate in China and perhaps in neighbouring countries without being detected. As such, reports of additional human cases and infections in animals would not be unexpected, especially with onset of winter in the Northern Hemisphere.

Although five small family clusters have been reported (including one among recent reported cases in Zhejiang province), evidence does not support sustained human-to-human transmission of this virus.

Overall public health risk assessment for avian influenza A(H7N9) virus: Sporadic human cases and small clusters would not be unexpected in previously affected and possibly neighbouring areas/countries of China. The current likelihood of community-level spread of this virus is considered to be low.

Continued vigilance is needed within China and neighbouring areas to detect infections in animals and humans. WHO advises countries to continue surveillance and other preparedness actions, including ensuring appropriate laboratory capacity. All human infections with non-seasonal influenza viruses such as avian influenza A(H7N9) are reportable to WHO under the IHR (2005).

The bottom line – particularly for those who were not following H5N1 in the `wild days’ of 2005-2008 - is that sporadic cases - and even a few clusters of cases - don’t tell us a whole lot about where any novel influenza virus is headed. The dramatic outbreaks in Indonesia, Turkey, and Vietnam in the middle of the last decade taught us that much.

If the transmissibility of avian flu among humans changes, I fully expect the WHO and the newshounds of Flublogia will pick up on it fairly quickly. For now, that doesn’t appear to be the case.

In the meantime, we should not be surprised to see a steady parade of scattered avian flu reports over the next few months. While a personal tragedy for those affected – and a serious concern to local public health authorities - they do give us an opportunity to better study and understand the virus, and how it spreads.

Something that could pay big dividends if either virus ever adapts successfully to humans.