# 8717

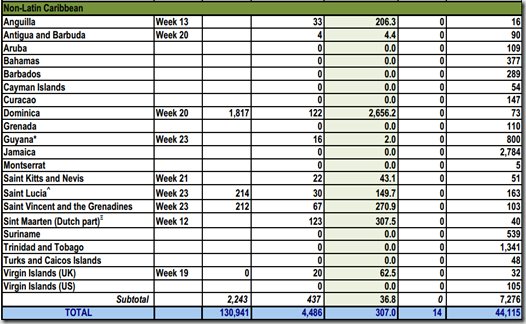

With the caveat that an exact count of cases is impossible, and the numbers we have are likely an undercount, yesterday PAHO (Pan American Health Organization) released their weekly update on Chikungunya, which shows a jump of nearly 30,000 cases across the Caribbean during the past week.

Last week (see PAHO Chikungunya Epidemiological Update – May 30th) the number of suspected and confirmed cases sat at just over 103,000.

This latest update (June 6th) sits at nearly 131,0000, with the vast majority of cases being reported on the Latin Caribbean islands, with Haiti and the Dominican Republic showing the fastest rise in cases.

Previously, Chikungunya has shown the ability to spread explosively among an immunologically naive population when the competent vectors (Aedes mosquitoes) and favorable environmental and societal conditions converge.

The 2005 outbreak on Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean reportedly resulted in the infection of roughly 1/3rd of that island’s population (266,000 case out of pop.770,000) in a matter of a few months.

In the past couple of days Crof has carried a number of reports from Haiti and the Dominican Republic (see Dr. Halverson on Haiti's chikungunya numbers) that give us some idea on how pervasive this virus has become in 6 short months in parts of the Caribbean.

While rarely fatal, Chikungunya can produce a severe fever and excruciating joint pain usually lasting for at least a week. Some studies (cite) indicate significant arthritis-like sequelae can persist for months or even years post-infection.

With an incubation period of between 3 and 7 days, and the enormous amount of international travel to, and from, the Caribbean, the concern is that this virus will soon migrate to other areas that also have a favorable climate and the right kind of mosquitoes.

Brazil is particularly at risk this summer with the FIFA World Cup, something we discussed yesterday.

But then, so is the United States, and even parts of Europe (Italy saw a mini-epidemic in 2007 when just one infected traveler started a chain of infection that eventually touched 300 people).

The good news, at least in most of the United States, is that most of us live and work in air-conditioned spaces, and live in regions that maintain pretty good mosquito control programs, and so we aren’t as apt to be continually exposed to (and bitten by) mosquitoes as people living in the Caribbean.

But as a native Floridian, I can assure you that it is pretty much impossible to totally avoid feeding our unofficial `state bird’.

The state of Florida is concerned enough that it has issued warnings to the public, and is actively Preparing For Chikungunya. In March the CDC held a Chikungunya Webinar and last December they released a CDC HAN Advisory On Recognizing & Treating Chikungunya Infection.

No one knows if Chikungunya will spread rapidly in the United States, like West Nile Virus has over the past 15 years, or produce infrequent and highly sporadic outbreaks, as has Dengue.

But given its rapid global expansion over the past nine years, no one in public health is taking the threat lightly.