My 2012 Influenza Timeline Graphic

# 9991

Three years ago, with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic behind us, I wrote a blog called An Increasingly Complex Flu Field, where we looked at the growing number of novel flu threats that were beginning to appear on our radar.

In addition to the venerable H5N1 virus, low path H9N2 and several LPAI H7 strains, I listed three up and coming `swine variant’ strains (H1N1v, H1N2v, H3N2v) that had recently jumped to humans, and were raising alarm bells (see CDC Teleconference & HAN Advisory On H3N2v).

Swine, like birds, are considered excellent `mixing vessels’ for influenza, and proved to the the crucible for the last (2009 H1N1) pandemic virus. They are susceptible to a variety of influenza types, and when simultaneously infected by two different strains, are capable of producing a hybrid – or reassortant – virus.

But as we’ve seen over the past few years, the number and variety of hosts for influenza reassortment go far beyond just pigs and birds.

Flu viruses can reassort in humans (see HK’s Dr. Ko Wing-man On Flu Reassortment Concerns), dogs (see Canine H3N2 Reassortant With pH1N1 Matrix Gene), and presumably in many other mammals (see Mixing Vessels For Influenza) including cats, seals, and even camels.

Over the past three years the number of newly emerged – or at least recently discovered – novel flu viruses has increased dramatically. Some of these viruses – like H5N6, H6N1, H7N9, and H10N8 – have already shown some limited ability to infect humans.

Others, like H5N8, H5N2, and H5N3 are related to viruses that can infect humans, but have not yet demonstrated the ability to do so. Whether they will maintain that status quo is unknowable.

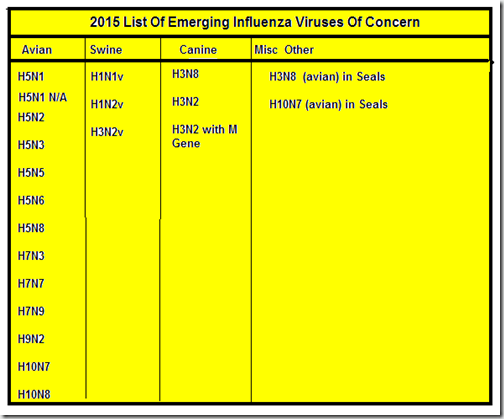

A partial list of influenza viruses of growing concern include:

I’ve purposefully excluded some recent influenza virus discoveries – like H17N10 and H18N11 found in bats, or the Novel Influenza C Virus In Bovines & Swine – because what little is known about these pathogens suggests they don’t pose a serious threat to human health at this time.

While most of the viruses I listed will likely never seriously threaten public health, this rapid increase in the number of pathogenic players is a concern. As they say, it only takes one. And we’ve literally gone from watching a half dozen or so `novel’ flu viruses to having to keep track of nearly two dozen over the past three years.

The threat becomes even larger when you consider that each of these subtypes can have multiple clades, or genotypes.

- The H7N9 virus – which emerged in China in 2013, at last count (see Nature report), has produced at least 48 genotypes, spread across three major clades, and it is likely that constellation of H7N9 variants continues to expand.

- Likewise, H5N1’s evolution from 1996, when it emerged as clade 0, has spawned a constantly expanding family tree (albeit, not all of these incarnations continue to circulate)

So when we discuss a flu virus – like H5N1, H7N9 or H5N8 – we aren’t talking about a single, monolithic threat. We are talking about an ever-expanding family of related viruses, which can vary considerably in their behavior and the threat they pose (see Differences In Virulence Between Closely Related H5N1 Strains).

The only real point we can draw from all of this is the number of potential influenza pandemic virus candidates has increased significantly over the past few years.

And with the geographic expansion of many of these viruses, the opportunities for them to interact with – an reassort with – other viruses, only increases. This is how North America ended up with two new HPAI H5 viruses (H5N2, H5N1 N/A) over the winter after the arrival of H5N8 in the Pacific Northwest last fall.

It is certainly possible that – over time – additional reassorted H5 viruses will appear in the United States or Canada. How they may end up affecting wild birds, poultry, or even humans is frankly . . . unpredictable.

Three years ago, all eyes were on the emerging swine variant viruses (see A Variant Swine Flu Review), which caused more than 300 infections across the Midwest in 2012. Although those viruses have receded from the headlines the past couple of summers, they haven’t gone away, and may surge again.

These swine viruses are important because – unlike many of the avian strains – they belong to the H1, H2, and H3 HA types that have led to all of the known pandemics of the past 130 years.

The progression of human influenza pandemics over the past 130 years has been H2, H3, H1, H2, H3, H1, H1 . . . . and while that doesn’t prove that an H5 or an H7 virus couldn’t adapt to humans (or hasn’t in the past), it has led some researchers to wonder whether a non H1, H2, or H3 virus has the `right stuff’ to spark a pandemic (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?).

This propensity for H1, H2, and H3 viruses to start human pandemics is another reason we keep our eyes on the H2N2 virus in birds (see H2N2: What Went Around, Could Come Around Again), H3N2 and H3N8 viruses canine viruses, the H3N8 seal virus, H2N2 and even H3N8 in horses (see Study: Dogs As Potential `Mixing Vessels’ For Influenza).

But whether a repeat in the H1-H3 cycle, or a deviation into the more exotic avian virus realms, another influenza pandemic is considered all but inevitable.

Two months ago (see WHO Warns On Evolving Influenza Threat) the World Health Organization advised:

Warning: be prepared for surprises

Though the world is better prepared for the next pandemic than ever before, it remains highly vulnerable, especially to a pandemic that causes severe disease. Nothing about influenza is predictable, including where the next pandemic might emerge and which virus might be responsible.

Given the growing number of candidate viruses in circulation, unlike the last interpandemic period, we may not have another three decades before the next pandemic appears.