#13,178

As we discussed last week in Nigeria's Lassa Fever Outbreak - Epi Week 7, since just after the 1st of the year, Nigeria has seen a nearly ten-fold increase in the number of Lassa Fever cases.

Although endemic in West Africa, between 2013 and early 2016 Nigeria had seen a steady decline in the number of Lassa Fever cases - and deaths - with the last significant outbreak reported in 2012.In early 2016 that trend began to change with outbreaks starting in Nigeria (see Nigeria: Lassa Fever Outbreak With 40 Fatalities), and then flaring up in both Benin and Togo (see ECDC: Rapid Risk Assessment On Lassa Fever In Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Germany & USA) but leveling out again for the second half of 2017.

Commonly carried by multimammate rats - a local rodent that often likes to enter human dwellings - Lassa fever exposure is typically via the urine or dried feces of infected rodents, although person-to-person transmission may occur with exposure to the blood, tissue, secretions, or excretions of an infected individual (cite CDC).

First a few excerpts from this week's Nigerian CDC Epidemiological Report, followed by a statement released today by the World Health Organization.

HIGHLIGHTS

- In the reporting Week 08 (February 19-25,2018) fifty four new confirmediI cases were recorded from eight States Edo (21), Ondo (9), Nasarawa (2), Ebonyi (18), Plateau(1),Kogi(1) Imo (1)and Ekiti (1) with ten new deaths in confirmed cases from five states Ondo (2), Edo (2), Plateau (1) Ekiti(1) and Ebonyi (4 and 2 probable deaths)

- From 1st January to 25th February 2018, a total of 1081 suspectedi cases, and 90 deaths have been reported from 18 activeiv States- (Edo, Ondo, Bauchi, Nasarawa, Ebonyi, Anambra, Benue, Kogi, Imo, Plateau, Lagos, Taraba, Delta, Osun, Rivers, FCT, Gombe and Ekiti) - Figure 1

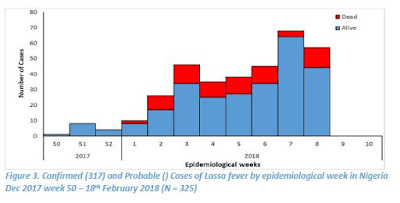

- Since the onset of the 2018, 325 cases have been classified as: 317 confirmed cases, 8 probable cases with 72 deaths (64 in Lab confirmed and 8 in probable)

- Case Fatality Rate in confirmed and probable cases is 22%

- Fourteen Health Care workers have been affected in six states –Ebonyi (7), Nasarawa (1), Kogi (1), Benue (1), Ondo (1) and Edo (3) with four deaths in Ebonyi (3) and Kogi (1)

- Predominant age group affected is age group 21-40 (Median Age = 34) - Figure 5

- The male to female ratio for confirmed cases is 2:1

- 69% of all confirmed cases are from Edo (43%) and Ondo (26%) states

- National RRT team (NCDC staff and NFELTP residents) batch B continues response support in Ebonyi, Ondo and Edo States

- Irrua Specialist Hospital has 42 cases on admission this weekend. FMC Owo has 21 isolation beds, all occupied

- A total of 2845 contacts have been identified from 18 active states and 1897 are currently being followed up

- WHO scaling up its support of the response at National and State levels

- NCDC is collaborating with ALIMA and MSF in Edo, Ondo and Anambra States to support case management

- NCDC deployed teams to four Benin Republic border states (Kebbi, Kwara, Niger and Oyo) for enhanced surveillance activities

- National Lassa fever multi-partner multi-agency Emergency Operations Centre(EOC) continues to coordinate the response activities at all levels

This statement from http://www.afro.who.int/

Abuja, Nigeria, 28 February 2018 — Nigeria’s Lassa fever outbreak has reached record highs with 317 laboratory confirmed cases, according to figures released by the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) this week.

Although endemic to the West African nation, Lassa fever has never reached this case count in Nigeria before. The number of confirmed cases during the past two months exceeds the total number of confirmed cases reported in 2017.

The outbreak has affected 18 states since the first case was detected on 1 January 2018, resulting in 72 deaths caused by the acute viral haemorrhagic fever. A total of 2,845 people who have come into contact with patients have been identified and are being monitored.

The World Health Organization is supporting the NCDC-led response with a focus on strengthening coordination (including through the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network), surveillance, contact tracing, laboratory testing, clinical management of patients, and community engagement. State health authorities are mobilizing doctors and nurses to work in Lassa fever treatment centres.

“The ability to rapidly detect cases of infection in the community and refer them early for treatment improves patients’ chances of survival and is critical to this response,” said Dr Wondimagegnehu Alemu, WHO Representative to Nigeria.

Health facilities are particularly overstretched in the southern states of Edo, Ondo and Ebonyi. WHO is working with health authorities, national reference hospitals and the Alliance for International Medical Action (ALIMA) to rapidly expand treatment centres and better equip them to provide patient care while reducing the risks to staff. Among those infected are 14 health workers, four of whom have died.

“Given the large number of states affected, many people will seek treatment in health facilities that are not appropriately prepared to care for Lassa fever patients and the risk of infection to healthcare workers is likely to increase,” said Dr Alemu.

Health workers are being trained in infection, prevention and control measures, such as the importance of wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) and isolating patients during treatment. WHO has provided an initial supply of PPE, other related materials and is assessing additional needs with a view to addressing them.

WHO is also supporting national response efforts in neighbouring Benin, where more than 20 suspected cases have been reported.

While primarily a regional threat, the incubation period of Lassa fever can run up to 21 days, and we've seen exported cases before. In 2014, in Minnesota: Rare Imported Case Of Lassa Fever, we saw the CDC's investigation into the 7th known imported case of Lassa into the United States.

Most of the earlier cases had been diagnosed abroad and the patients were then airlifted to the US for treatment, but two previous cases (2004 in New Jersey (MMWR) & 2010 in Pennsylvania (EID Journal)) involved travelers who arrived in the US without knowing they had been infected.Again, in 2016, exported cases turned up in several countries, including Germany and Sweden (see Germany's RKI Statement On Lassa Fever Cluster In Cologne & WHO Lassa Fever Update - Sweden (Imported)).

In 2016 the ECDC published a Rapid Risk Assessment on the spread of Lassa Fever out of West Africa. While the risk of seeing Lassa Fever outside of West Africa was determined to be low, they authors wrote:

The two imported cases of Lassa fever recently reported from Togo indicate a geographical spread of the disease to areas where it had not been recognised previously. Delays in the identification of viral haemorrhagic fevers pose a risk to healthcare facilities.

Therefore, Lassa fever should be considered for any patient presenting with suggestive symptoms originating from West African countries (from Guinea to Nigeria) particularly during the dry season (November to May), a period of increased transmission, and even if a differential diagnosis such as malaria, dengue or yellow fever is laboratory-confirmed.If you count the unprecedented West African Ebola epidemic in 2014, and last year's record setting Monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria, this year's record surge in Lassa Fever cases marks the third outbreak `anomaly' in the region in recent years.

While the world has been relatively lucky so far, and these outbreaks have been largely contained, that luck may not hold forever.A reminder that in this increasingly interconnected and mobile world that localized outbreaks - no matter how remote - aren't guaranteed to remain such, and that without a proactive response they can very quickly turn into public health threats anywhere in the world.