|

| Credit CDC |

#13,571

A few of the many enduring questions surrounding the 1918 Pandemic are:

- What made it so much deadlier than the others we've seen either before or since?

- What were the origins of this deadly influenza virus?

- What was behind the infamous `W shaped curve' showing death rates among those in their teens, 20s, and 30s to be much higher than in previous influenza years, while death rates were in lower in those over 65?

- And perhaps most importantly, could we see another like it?

We've looked a literally dozens of studies over the years attempting to answer these - and other - questions. And scholarly opinions vary. Some lay the blame on a runaway cytokine storm - while others cite a Viral-Bacterial Copathogenesis - as likely causing the extremely high death rates.

In recent years we've seen evidence suggesting that childhood HA imprinting could leave some age groups more vulnerable to certain flu subtypes. And increasingly we're learning about how host genetics may play a role in the susceptibility and outcome of influenza infection in some people.

Other factors that have been discussed include the crowding together and movement of troops during WWI, malnutrition, co-infection with other pathogens (e.g. Malaria, Measles, etc.), or simply that the emerging 1918 virus was a particularly lethal viral brew.A pretty good case can be made for these contributing factors, and I suspect all played some role. And in time, we may learn of other important factors as well.

As to whether a 1918 pandemic could repeat itself today, the global conditions and scientific acumen that existed 100 years ago are far different from today. We have scientific and medical advances that would probably - at least for a some segments of the population - help mitigate the impact of another severe pandemic.

But at the same time, we are far more dependent upon our supply chains, and interruptions in the production and delivery of food, fuel, energy and pharmaceuticals could have huge impacts on our society (see Supply Chain Of Fools (Revisited)).Low resource countries of the world, however, could easily find themselves in a similar logistical situation to what was seen in 1918 (see Are We Prepared to Help Low-Resource Populations Mitigate a Severe Pandemic?

Those who have not already seen it should take the time to watch last May's

Johns Hopkins day-long pandemic table top exercise (see CLADE X: Archived Video & Recap), which presents a sobering look at an all-too-possible future.

If you don't have the time to watch the entire 8 hour exercise, I would urge you to at least view the 5 minute wrap up video. It will give you some idea of the possible impact of a severe - but not necessarily `worst case' - pandemic.Today we've a long open-access review article, published in Frontiers in Cellular & Infection Biology , that takes a long look at what we know (or at least, think we know) about the 1918 pandemic.

Since there is far too much here to realistically excerpt, I've just included the link and the abstract below. You'll want to set aside some time to read this review in its entirety, and keep it handy as a reference.

Review ARTICLE

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.,

08 October 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00343

Back to the Future: Lessons Learned From the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Kirsty R. Short1,2,Katherine Kedzierska3* and Carolien E. van de Sandt3,4*

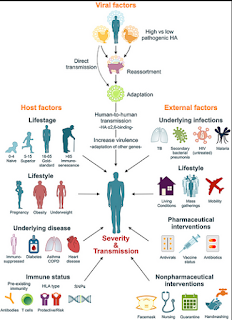

2018 marks the 100-year anniversary of the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed ~50 million people worldwide. The severity of this pandemic resulted from a complex interplay between viral, host, and societal factors. Here, we review the viral, genetic and immune factors that contributed to the severity of the 1918 pandemic and discuss the implications for modern pandemic preparedness.

We address unresolved questions of why the 1918 influenza H1N1 virus was more virulent than other influenza pandemics and why some people survived the 1918 pandemic and others succumbed to the infection. While current studies suggest that viral factors such as haemagglutinin and polymerase gene segments most likely contributed to a potent, dysregulated pro-inflammatory cytokine storm in victims of the pandemic, a shift in case-fatality for the 1918 pandemic toward young adults was most likely associated with the host's immune status.

Lack of pre-existing virus-specific and/or cross-reactive antibodies and cellular immunity in children and young adults likely contributed to the high attack rate and rapid spread of the 1918 H1N1 virus. In contrast, lower mortality rate in in the older (>30 years) adult population points toward the beneficial effects of pre-existing cross-reactive immunity. In addition to the role of humoral and cellular immunity, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that individual genetic differences, especially involving single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), contribute to differences in the severity of influenza virus infections.

Co-infections with bacterial pathogens, and possibly measles and malaria, co-morbidities, malnutrition or obesity are also known to affect the severity of influenza disease, and likely influenced 1918 H1N1 disease severity and outcomes.

Additionally, we also discuss the new challenges, such as changing population demographics, antibiotic resistance and climate change, which we will face in the context of any future influenza virus pandemic. In the last decade there has been a dramatic increase in the number of severe influenza virus strains entering the human population from animal reservoirs (including highly pathogenic H7N9 and H5N1 viruses). An understanding of past influenza virus pandemics and the lessons that we have learnt from them has therefore never been more pertinent.(Continue . . .)