|

| Credit CDC |

#13,836

Lassa fever is a Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF) endemic to a handful of West African nations - commonly carried by multimammate rats - a local rodent that often likes to enter human dwellings.

Exposure is typically through the urine or dried feces of infected rodents, and roughly 80% who are infected only experience mild symptoms.The incubation period runs from 10 days to 3 weeks, and the overall mortality rate is believed to be in the 1%-2% range, although it runs much higher (15%-20%) among those sick enough to be hospitalized.

Like many other hemorrhagic fevers, person-to-person transmission may occur with exposure to the blood, tissue, secretions, or excretions of an individual (cite CDC Lassa Transmission).While endemic in West Africa, between 2013 and early 2016 Nigeria saw a steady decline in the number of Lassa Fever cases - and deaths - with the last significant outbreak reported in 2012.

In 2016 that trend began to reverse itself with outbreaks starting in January (see Nigeria: Lassa Fever Outbreak With 40 Fatalities), and then flaring up in both Benin and Togo (see ECDC: Rapid Risk Assessment On Lassa Fever In Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Germany & USA).Once again, in early 2018 we began to see another major surge in cases (see WHO Statement & Nigerian CDC Update On Lassa Fever Epidemic), which exceeded (by far) the previous two years. Based on the latest report from Nigeria's CDC, that west African nation appears to be off to another early start to their Lassa season.

2019 LASSA FEVER OUTBREAK SITUATION REPORT

27 January 2019

HIGHLIGHTS

- In the reporting Week 04 (January 21 - 27, 2019) seventy-seven new confirmed cases were reported from Edo(24), Ondo(28), Ebonyi(5), Bauchi(3), Plateau(5), Taraba(3), Gombe(1), Kaduna(1), Kwara(1), FCT(1), Benue(2), Rivers(1) Kogi(1) and Enugu(1) States with eleven new deaths in Edo(4), Ondo(2), Benue(1), Rivers(1) Plateau(2) Taraba(1) and Bauchi(1)

- From 1 st to 27 th January 2019, a total of 538 suspected i cases have been reported from 16 States. Of these, 213 were confirmed positive, 2 probable and 325 negative (not a case)

- Since the onset of the 2019 outbreak, there have been 42 deaths in confirmed cases. Case fatality rate in confirmed cases is 19.7%

- Sixteen States (Edo, Ondo, Bauchi, Nasarawa, Ebonyi, Plateau, Taraba, FCT, Adamawa and Gombe, Kaduna, Kwara, Benue, Rivers Kogi and Enugu) have recorded at least one confirmed case across 40 Local Government Areas- Figure 1

- In the reporting week 04, one new healthcare worker was affected in Enugu State- contact of an Adamawa confirmed case. A total four health care workers have been affected since the onset of the outbreak in two States – Ondo (2), Ebonyi (1) and Enugu(1) with no death

- One hundred and two patients are currently being managed at Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital(ISTH) treatment Centre (34), Federal Medical Centre Owo (40), Bauchi (5), Plateau(8) Taraba(3) Ebonyi(6) and Others(6) States

- A total of 2070 contacts have been identified from eight states. Of these 1673 (80.8%) are currently being followed up, 361 (17.4%) have completed 21 days follow up. 23 (1.1%) symptomatic contacts have been identified, of which 13 (0.6%) have tested positive from three states (Edo -2, Ebonyi-5 and Plateau-6 )

- Multi sectoral one health national rapid response team (NFELTP residents, Federal Ministry of Agricultural and Federal Ministry of Environment) deployed to Ondo, Edo, Ebonyi and Plateau/Bauchi

- National Lassa fever multi-partner, multi-sectoral Emergency Operations Centre(EOC) continuesto coordinate the response activities at all levels

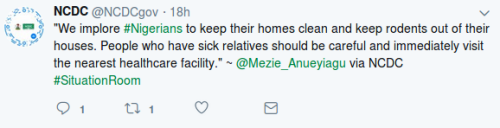

Yesterday afternoon Nigeria's CDC posted a barrage of tweets on social media (see below) on the epidemic, urging people to seek medical care if they develop symptoms.

Less than a year ago, the World Health Organization included Lassa Fever in their short List Of Blueprint Priority Diseases, for which there is an urgent need for additional research and drug development.

- Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

- Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

- Nipah and henipaviral diseases

- Rift Valley fever (RVF)

- Zika

- Disease X

While primarily a regional threat, the incubation period of Lassa fever can run up to 21 days, and we've seen exported cases before. In 2014, in Minnesota: Rare Imported Case Of Lassa Fever, we saw the CDC's investigation into the 7th known imported case of Lassa into the United States.

Most of the earlier cases had been diagnosed abroad and the patients were then airlifted to the US for treatment, but two previous cases (2004 in New Jersey (MMWR) & 2010 in Pennsylvania (EID Journal)) involved travelers who arrived in the US without knowing they had been infected.Again, in 2016, exported cases turned up in several countries, including Germany and Sweden (see Germany's RKI Statement On Lassa Fever Cluster In Cologne & WHO Lassa Fever Update - Sweden (Imported)).

In 2016 the ECDC published a Rapid Risk Assessment on the spread of Lassa Fever out of West Africa. While the risk of seeing Lassa Fever outside of West Africa was determined to be low, they authors wrote:

The two imported cases of Lassa fever recently reported from Togo indicate a geographical spread of the disease to areas where it had not been recognised previously. Delays in the identification of viral haemorrhagic fevers pose a risk to healthcare facilities.

Therefore, Lassa fever should be considered for any patient presenting with suggestive symptoms originating from West African countries (from Guinea to Nigeria) particularly during the dry season (November to May), a period of increased transmission, and even if a differential diagnosis such as malaria, dengue or yellow fever is laboratory-confirmed.A reminder that in this increasingly interconnected and mobile world that localized outbreaks - no matter how remote - aren't guaranteed to remain such, and that without a proactive response they can very quickly turn into public health threats anywhere in the world.