#13,893

Although it may seem a remote concern to most Americans, the continental United States has a number of active, and potentially dangerous volcanoes.

Last October, in USGS Updated Volcano Threat Assessment - 2018, we saw that 11 of the 18 very highest threat volcanoes on U.S. soil are located in the Western United States - 4 in Washington, 4 in Oregon & 3 in California. (note: Yellowstone is ranked 21st).

Additionally, 39 volcanoes are listed as posing a `high threat', and 49 are ranked as a `moderate' threat. These are not predictions of which volcanoes are apt to blow next, but rather an assessment of the potential severity of impacts that future eruptions might generate.

We've discussed eruptive hazards before - both internationally (see here, here, and here), and domestically (see Washington State: Volcano Awareness Month). While earthquake damage is generally localized, volcanic eruptions (and tsunamis) can affect property and populations thousands of miles away.

- In 2010 airline traffic in Europe was disrupted by the eruption of Iceland's Eyjafjallajökull volcano (see study The vulnerability of the European air traffic network to spatial hazards), halting many flights for nearly a week.

- When Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines in 1991, within a year its aerosol cloud had dispersed around the globe, resulting in `an overall cooling of perhaps as large as -0.4°C over large parts of the Earth in 1992-93’ (see USGS The Atmospheric Impact of the 1991 Mount Pinatubo Eruption).

- In 1783 the Craters of Laki in Iceland erupted and over the next 8 months spewed clouds of clouds of deadly hydrofluoric acid & Sulphur Dioxide, killing over half of Iceland’s livestock and roughly 25% of their human population. These noxious clouds drifted over Europe, and resulted in widespread crop failures and thousands of deaths from direct exposure to these fumes (see 2012 UK: Civil Threat Risk Assessment)

All of which means you don't have to live in the shadow of one of these slumbering giants to be impacted by an eruption. But, according to a new report from the USGS, roughly 200,000 Californian's do work, live, or pass through that state's volcanic hazard zones on a daily basis.

Some volcanic hazards - like ash fall - can spread hundreds of miles. And even a light dusting of volcanic ash can wreak havoc on power lines, and airline traffic.Suggesting that the next `big one' to hit California might be eruptive, rather than an earthquake.

Due to its length (58 pages) I've only posted the abstract, so follow the link to download the PDF in its entirety.

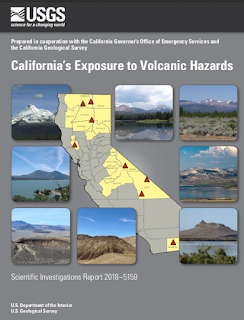

California’s Exposure to Volcanic Hazards

Scientific Investigations Report 2018-5159

Prepared in cooperation with the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and the California Geological Survey

By: Margaret Mangan, Jessica Ball, Nathan Wood, Jamie L. Jones, Jeff Peters, Nina Abdollahian, Laura Dinitz, Sharon Blankenheim, Johanna Fenton, and Cynthia Pridmore

https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20185159

Links

Document: Report (33.6 MB pdf)

First posted February 25, 2019

Volcano Science Center

U.S. Geological Survey

345 Middlefield Road, MS 910

Menlo Park, CA 94025

The potential for damaging earthquakes, landslides, floods, tsunamis, and wildfires is widely recognized in California. The same cannot be said for volcanic eruptions, despite the fact that they occur in the state about as frequently as the largest earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault. At least ten eruptions have taken place in the past 1,000 years, and future volcanic eruptions are inevitable.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) national volcanic threat assessment identifies eight young volcanic areas in California as moderate, high, or very high threat. Of the eight volcanic areas that exist in California, molten rock resides beneath at least seven of these—Medicine Lake volcano, Mount Shasta, Lassen Volcanic Center, Clear Lake volcanic field, the Long Valley volcanic region, Coso volcanic field, and Salton Buttes—and are therefore considered “active” volcanoes producing volcanic earthquakes, toxic gas emissions, hot springs, geothermal systems, and (or) ground movement.

The USGS California Volcano Observatory in Menlo Park, California, monitors these potentially hazardous volcanoes to help communities and government authorities understand, prepare for, and respond to volcanic activity. Although volcanic activity can sometimes be forecast, eruptions, like earthquakes or tsunamis, cannot be prevented. Understanding the hazards and identifying what and who is in harm’s way is the first step in mitigating volcanic risk and building community resilience to volcanic hazards.

This report, which was prepared in collaboration with the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and the California Geological Survey, provides a broad perspective on the state’s exposure to volcanic hazards by integrating volcanic hazard information with geospatial data on at-risk populations, infrastructure, and resources. This information is intended to prompt site- and sector-specific vulnerability analyses and preparation of hazard mitigation and response plans.

Suggested Citation

Mangan, M., Ball, J., Wood, N., Jones, J.L., Peters, J., Abdollahian, N., Dinitz, L., Blankenheim, S., Fenton, J., and Pridmore, C., 2019, California’s exposure to volcanic hazards: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2018–5159, 49 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20185159.

While I don't recommend that anyone lie awake at night worrying about the next potential disaster, every home should be at least minimally prepared to deal with one if it happens.

So . . . if a disaster struck your region today, and the power went out, stores closed their doors, and water stopped flowing from your kitchen tap for the next 7 to 14 days . . . do you already have:

- A battery operated NWS Emergency Radio to find out what was going on, and to get vital instructions from emergency officials

- A decent first-aid kit, so that you can treat injuries

- Enough non-perishable food and water on hand to feed and hydrate your family (including pets) for the duration

- A way to provide light when the grid is down.

- A way to cook safely without electricity

- A way to purify or filter water

- A way to stay cool (fans) or warm when the power is out.

- A small supply of cash to use in case credit/debit machines are not working

- An emergency plan, including meeting places, emergency out-of-state contact numbers, a disaster buddy, and in case you must evacuate, a bug-out bag

- Spare supply of essential prescription medicines that you or your family may need

- A way to entertain yourself, or your kids, during a prolonged blackout

Some other preparedness resources you might want to revisit include:

The Gift Of Preparedness - Winter 2018

#NatlPrep: Revisiting The Lloyds Blackout Scenario

#NatlPrep : Because Pandemics Happen

Disaster Planning For Major Events

All Disaster Responses Are Local