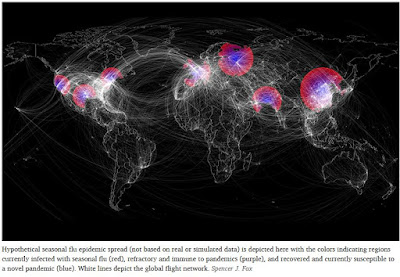

Credit Spencer J. Fox

#13,946

Spring officially arrived a little over 12 hours ago in the Northern Hemisphere, and while novel influenza activity has been fairly subdued for the past year, this is the time of year when we tend to see the emergence of new flu viruses.

- A decade ago, a new soon-to-become-a-pandemic H1N1 virus was beginning to spread from pigs to humans in Mexico, although we wouldn't be alerted until the last week of April, 2009.

- Six years ago, three patients were hospitalized in Eastern China suffering from an `atypical pneumonia', but on March 31th, 2013 it was announced to the world as a newly emerging avian H7N9 virus.

- On April 23rd, 2014 the newshounds of Flutrackers picked up a Chinese language report of a farmer from Nambu county, Sichaun Province hospitalized with a severe - and unidentified - pneumonia. This turned out to be the first known human infection with H5N6.

- A bit earlier last year (mid-February 2018) Jiangsu China Reported the 1st Novel H7N4 Human Infection.

- And although it wasn't an influenza virus, the first known (and retrospectively identified) MERS outbreak occurred in April of 2012 in Jordan (see Serological Testing Of 2012 Jordanian MERS Outbreak)

- An even older example of a non-influenza epidemic, the first known Nipah outbreak - in Malaysia and Singapore - which infected more than 265 (and killing 106) emerged in March of 1999.

Some non-spring outbreaks of note include:

- The 2003 SARS epidemic appears to have started in China the previous fall, but was covered up by Chinese authorities until it jumped to Vietnam and Hong Kong in March.

- The first (of 3) H10N8 infections reported in China was announced in early December of 2013

Using a computer model, the authors found evidence of a narrow window of opportunity for pandemic emergence, and proposed two possible factors behind this trend.Given the turning of the seasons, a look back seems in order. First some excerpts from a press release from the University of Texas At Austin, and a link and some excerpts from the study.

Cracking the Code: Why Flu Pandemics Come At the End of Flu Season

Oct. 19, 2017

You might expect that the risk of a new flu pandemic — or worldwide disease outbreak — is greatest at the peak of the flu season in winter, when viruses are most abundant and most likely to spread. Instead, all six flu pandemics that have occurred since 1889 emerged in spring and summer months. And that got some University of Texas at Austin scientists wondering, why is that?

Based on their computational model that mimics viral spread during flu season, graduate student Spencer Fox and his colleagues found strong evidence that the late timing of flu pandemics is caused by two opposing factors: Flu spreads best under winter environmental and social conditions. However, people who are infected by one flu virus can develop temporary immune protection against other flu viruses, slowing potential pandemics. Together, this leaves a narrow window toward the end of the flu season for new pandemics to emerge.

The researchers’ model assumes that people infected with seasonal flu gain long-term immunity to seasonal flu and short-term immunity to emerging pandemic viruses. The model incorporates data on flu transmission from the 2008-2009 flu season and correctly predicted the timing of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

(Continue . . . )

Seasonality in risk of pandemic influenza emergence

Spencer J. Fox , Joel C. Miller, Lauren Ancel Meyers

Published: October 19, 2017

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005749

Abstract

Influenza pandemics can emerge unexpectedly and wreak global devastation. However, each of the six pandemics since 1889 emerged in the Northern Hemisphere just after the flu season, suggesting that pandemic timing may be predictable.

Using a stochastic model fit to seasonal flu surveillance data from the United States, we find that seasonal flu leaves a transient wake of heterosubtypic immunity that impedes the emergence of novel flu viruses. This refractory period provides a simple explanation for not only the spring-summer timing of historical pandemics, but also early increases in pandemic severity and multiple waves of transmission.

Thus, pandemic risk may be seasonal and predictable, with the accuracy of pre-pandemic and real-time risk assessments hinging on reliable seasonal influenza surveillance and precise estimates of the breadth and duration of heterosubtypic immunity.(Continue . . )

While there is no way to know whether the next few months will spawn the next big public health crisis, the spring and early summer does appear to be conducive to the emergence of new viruses.

Most of these viruses sputter noisily for a few months, and either die out completely (i.e. SARS), or become a low-level endemic threat like MERS-CoV. Only occasionally do they reach their full pandemic potential.

But the next pandemic will come. This year, next year, five years from now . . .And once we recognize its presence, and its true potential, the time for preparation will have passed. With our modern conveyances, and highly mobile society, the next pandemic will spread with remarkable speed.

Over the past year we've seen a resurgence in pandemic preparedness efforts by the United States government, the World Health Organization, and other entities. So, on this first full day of spring, a few blogs worth reviewing as you consider your own vulnerability to the next pandemic:

Last May Johns Hopkins presented a day-long pandemic table top exercise (see CLADE X: Archived Video & Recap), which provides a sobering look at a plausible pandemic where hundreds of millions of people could die, many from indirect causes.

If you don't have the time to watch the entire 8 hour exercise, I would urge you to at least view the 5 minute wrap up video. It will give you some idea of the possible impact of a severe - but not necessarily `worst case' - pandemic.

|

| Recap Video |

Earlier this month we looked at the newly released WHO Global Influenza Strategy 2019-2030, with the the stated goals of preventing seasonal influenza, controlling the zoonotic spread of influenza to humans, and preparing for the next influenza pandemic.

Last December the WHO engaged 40 countries in a Global EOC Pandemic Flu Exercise (GEOCX).

Last November the CDC released their 2018 Interim Guidance On Allocating & Targeting Pandemic Influenza Vaccine, with their ambitious aim to:

- `. . . . vaccinate all persons in the United States (U.S.) who choose to be vaccinated, prior to the peak of disease'

- . . . . to have sufficient pandemic influenza vaccine available for an effective domestic response within four months of a pandemic declaration'

- ` . . . to have first doses available within 12 weeks of the President or the Secretary of Health and Human Services declaring a pandemic'

In October of last year, in WHO: On The Inevitability Of The Next Pandemic, we looked at the global consensus that it is a matter of when - not if - the next pandemic arrives.

Also in October, in JAMA: Osterholm Interview - Our Vulnerability To Pandemic Flu, we looked at some of the reasons why a future pandemic could equal or even exceed the toll of the Spanish flu of 100 years ago.

While we enjoy the relatively lack of novel flu news, we need to be using this time wisely. While the following quote is more than a dozen years old, it is just as true today as it was in 2006:

“Everything you say in advance of a pandemic seems alarmist. Anything you’ve done after it starts is inadequate."- Michael Leavitt, Former Secretary of HHSAll reasons why, we - along with the rest of the world - need to find the foresight, fortitude, and political will to do something substantial to prepare before the next crisis strips us of that opportunity completely.

For more on pandemic planning and preparedness, you may wish to revisit:

#NatlPrep : Because Pandemics Happen

Pandemic Planning For Business

The Pandemic Preparedness Messaging Dilemma